Introduction

Thoracic spine pain syndrome is far less common than lumbosacral or cervical pain [1]. This pathology is often caused by work-related overload, especially sedentary work, lack of regular exercise, and adopting incorrect postures [1, 2]. Thoracic spine pain may result, for instance, from degenerative joint lesions (zygapophyseal facet, costovertebral joint, and costotransverse joint) [3]. In consequence, there is a reflex contraction of the soft, paraspinal tissues, including muscles, fascia, and ligaments. On the other hand, the thoracic spine pain syndrome may be originally of muscle or fascial origin, due to overloading of the muscles or fascia, and be myofascial in nature [1, 4].

Various forms of therapy are described in the literature. Minimally invasive treatment methods are used, such as erector spinae plane block, intra-articular thoracic zygapophyseal (facet) joint injection, thoracic medial branch block, costotransverse joint injection, and costovertebral joint injection, which are performed using ultrasound [5]. Dry needling is often used in the case of ailments of muscular origin [6]. Deep, uncontrolled injections into the thoracic spine may lead to pneumothorax [7]. The various forms of physiotherapy that are often used are not entirely effective. Therefore, medicine continues to seek easy, safe, and effective therapies. One of them is spinal mesotherapy (local intradermal therapy) [8]. Mesotherapy involves multipoint intradermal microinjections, 3–4-mm deep, at an angle of 15–30o. Drugs are administered, as well as medical devices. The mechanism of action is multidirectional. It involves irritation of receptors in the skin and subcutaneous tissue, and activation of repair mechanisms (stimulation of the immune and blood systems) associated with the injection and the substance administered. The endogenous opioid system is activated. Endorphin levels are increased [8–10]. As the drug is administered close to the intended site of action, mesotherapy has a rapid onset of action, a prolonged local effect, and a drug/formulation sparing effect [11]. There are numerous studies in the literature confirming the effectiveness and safety of spinal mesotherapy using, for example, diclofenac [12], dexketoprofen [13], collagen type I or lignocaine [14]. The use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs can cause several side effects, especially in geriatric patients. An alternative is the use of collagen type I. Injectable collagen I is of porcine origin. In this study, we used a medical device based on collagen (100 µg/2 ml vials), hypericum, sodium chloride, and water, which was injected [15]. The aim of mesotherapy is to relax tight tissues, improve spinal mobility, and reduce pain. Spinal mesotherapy is typically performed once a week, in a five-repetition cycle [16].

The purpose of the study was to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of thoracic spinal mesotherapy with collagen type I versus lignocaine.

Material and methods

Study design

Patients with chronic localised thoracic spine pain syndrome were analysed retrospectively. All patients were examined by the same physician (orthopaedist). Computed tomography (CT) and/or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) diagnostic images of the thoracic spine were evaluated. Patients were divided into 2 groups: group A (n = 65), in which collagen mesotherapy was performed, and group B (n = 65), in which lignocaine 1% mesotherapy was performed. Patients were informed about the efficacy and safety of both preparations. The choice of formulation was agreed with the patient. Collagen mesotherapy was a more expensive procedure, so not every patient agreed. Patients allergic to lignocaine had collagen mesotherapy automatically performed. Patients were treated between January 1, 2018 and June 31, 2024.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Study inclusion criteria were:

local pain along the thoracic spine (back extensors); often described by the patient as “pain between the shoulder blades”, not radiating to the chest (no signs of intercostal neuralgia),

chronic nature of the ailment (more than 12 weeks),

CT and/or MRI diagnostic images (not older than 6 months),

no allergy to collagen type I or to lignocaine,

sedentary work for a minimum of 5 years, 5 times a week on average, for an average of 8 hours.

Study exclusion criteria were:

Study protocol

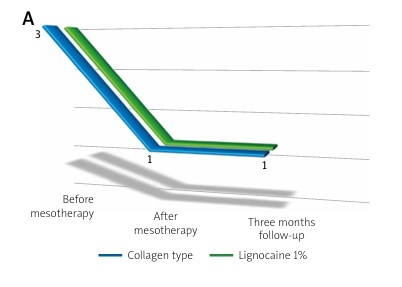

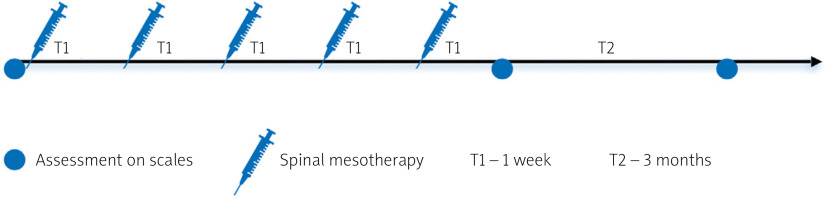

Figure 1 shows the diagnostic and therapeutic scheme. Before the therapy, patients were assessed using the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS; 0–10) [17] and the Laitinen scales (0–16), which take into account: pain intensity (0–4), pain frequency (0–4), painkiller intake (0–4), and motor activity limitation (0–4) [18]. This was followed by mesotherapy of the thoracic spine. Mesotherapy was repeated 5 times, at weekly intervals. One week after the end of the therapy and after another 3 months, the patients were reassessed using the same scales.

Figure 2 shows the scheme for thoracic spine mesotherapy. The injections were administered intradermally, laterally from the midline of the spine about 1–1.5 cm, along the spinal extensors. They were delivered at a depth of 3–4 mm and an angle of 15–30o, with about 0.05–0.1 ml of type I collagen or lignocaine 1%. A total of approximately 25 microinjections were performed during 1 session, administering a 2 ml ampule of collagen type I or a 2 ml ampule of lignocaine 1%.

Sample size

Calculation of the sample size: to achieve a power of 80% with an α of 5% and a standardized effect size of 35%, each group should consist of at least 65 participants.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis with R environment, version 4.3.2 was performed. The results were presented as mean with standard deviation and median with interquartile range. Normality in subgroups for continuous and quasi-continuous variables was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. The age variable has a normal distribution and equal variances between groups, as assessed by the Levene test. Non-parametric tests were used for the other comparisons because of the non-normal distribution of variables. There were identical Laitinen scale results at multiple time points in the data set, so the ANOVA Friedman test was not applicable. The Agresti-Pendergrast test to compare Laitinen and VAS scales at different time points and between groups was used. As the post hoc test, the Wilcoxon signed rank test was utilized. The p-value was corrected for multiple comparisons with the Hochberg procedure. A χ2 test to compare the sex distribution between the groups was used. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The retrospective analysis included 130 participants, consisting of 49 men and 81 women aged from 29 to 68, with chronic thoracic spine pain syndrome confirmed by physical examination and medical imaging tests: CT or MRI. The medical examination, determination of eligibility for mesotherapy, the mesotherapy procedure, and the assessment on scales were performed by the same doctor, an orthopaedist. There was no statistically significant difference in sex or age between the groups. Table I presents the parameters of the participants.

Table I

Participant characteristics. Scale scores at study time points

| Study groups | Spinal mesotherapy | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group A: collagen (n = 65) | % | Group B: lignocaine 1% (n = 65) | % | |

| Men | 22 | 34 | 27 | 42 |

| Women | 43 | 66 | 38 | 58 |

| Age [minimum] | 30 | 29 | ||

| Age [maximum] | 68 | 68 | ||

| Age [mean, SD] | 49 ±9.23 | 50 ±9.70 | ||

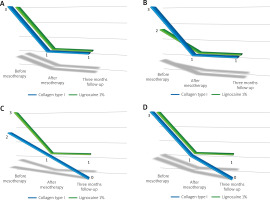

Both treatment methods effectively reduced pain (measured by VAS), its frequency and intensity, painkiller use, and motion limitation (the Laitinen scale). Collagen seems to act more slowly than lignocaine, and its effect is more prominent at the 3-month follow-up visit. Lignocaine, on the other hand, provides quicker relief but acts for a shorter time. It is worth mentioning that the difference between lignocaine and collagen at the 3-month follow-up is much more significant than immediately after a cycle of mesotherapy. Table II presents the values on the scales at different time points, and Table III presents the comparison at different time points in the study groups.

Table II

Scale scores at study time points

Table III

Comparison at different time points in the study groups

Below, Figure 3A shows the change in the Laitinen scale score for pain intensity, Figure 3B for pain frequency, Figure 3C for painkiller intake, and Figure 3D for motor activity limitation. In each case, a decrease in the Laitinen scale score was observed.

Fig. 3

Change in the Laitinen scale score for: A) pain intensity, B) pain frequency, C) painkiller intake, D) motor activity limitation in the study groups.

No serious treatment-related adverse effects were observed during the treatment period (5 mesotherapy treatments) or during the follow-up period. No allergies to the administered preparations were observed. The only complaint observed was local pain during the mesotherapy procedure. After collagen the pain persisted for up to 24 hours, and after lignocaine it subsided up to 15 minutes after the procedure.

Discussion

To date, many studies have been published on the efficacy and safety of cervical and lumbar spine mesotherapy, but there are no studies reporting on the efficacy and safety of collagen mesotherapy for chronic thoracic spine pain syndrome. Based on database analysis, no such studies were found. This paper reports the first one.

The present results show a decrease in pain on both the VAS and Laitinen scales after completing 5 mesotherapy treatments in groups A and B. Moreover, the reduced level of thoracic spine pain persisted after a 3-month follow-up, but it seems that the effect was better after collagen mesotherapy. The authors reported similar results in an article published in early 2024, which used a regimen of 5 mesotherapy treatments, with weekly intervals, using collagen mesotherapy or with lignocaine for lumbosacral spinal pain syndrome [14].

Godek [19] published the results of a randomised study in 2019, in which subcutaneous collagen injections are not inferior in terms of effectiveness to epidural and periarticular injections in the treatment of lumbar spondylosis. In contrast, in this study, injections were not performed using the mesotherapy technique as in our study.

In 2019, Pavelka et al. [20] also published the results of their study, which aimed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of injectable collagen in patients with low back pain. Collagen injections were also performed subcutaneously. The analgesic effectiveness of locally acting injectable collagen and an analgesic sparing effect when compared to local anaesthetics were demonstrated.

Numerous studies have been reported in the literature. Mesotherapy injections were performed by Ferrara et al. [21] in the course of chronic neck pain in spondylarthrosis, using diclofenac; by Brauneis et al. [11] in the course of spinal pain in a randomized controlled study; and by Tekin et al. [22] in a randomized controlled study assessing intradermal sterile water injection for low back pain in the emergency department. Akbas et al. [13] compared the efficiency of mesotherapy with systemic therapy in pain control in patients with lumbar disk herniation.

In addition, it is worth noting that mesotherapy is a stage of treatment. It is necessary to assess risk factors, to reduce or modify them. Injectable therapy should be implemented, which will relax tense tissues, improve mobility, and reduce pain. Then, the process of physical therapy plays a very important role. A patient who is prepared for physiotherapy can practise in better conditions [23]. Rising scientific evidence for the use of collagen therapy, including at the molecular level, supports its increasing use [24, 25].

Study limitations

An important limitation is the retrospective nature of the study. It is necessary to conduct prospective, randomized research, with a larger group of patients and longer follow-up, and including a control group receiving saline. In addition, in the period after the therapy, until the follow-up visit, patients could use other, complementary forms of therapy, which might have affected the final result. Moreover, in future studies, it is worth assessing sagittal balance in postural X-ray tests of the spine, before and after treatment.