Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic inflammatory disorder having a major manifestation as peripheral arthritis, but also with systemic manifestations. The focus of the treating physicians is to control the disease activity using disease modifying agents and biologicals with little emphasis on addressing the underlying psychiatric morbidity.

Various studies have shown the prevalence of depression and anxiety in RA patients to be as low as 6% and 2.5% to as high as 66% and 70%, respectively [1–4]. Studies using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) revealed a lower prevalence of anxiety and depression [1–3], while the study using Research Diagnostic Criteria for the International Classification of Diseases-10 (ICD-10) showed a higher prevalence of anxiety and depression [4].

A study from India reported the prevalence of anxiety and depression to be 25% and 17%, respectively, of RA patients using HADS [5]. Also, there are studies reporting lower prevalence of anxiety and depression from South East Asia, while a study from Egypt reported a higher prevalence [1–5].

The prevalence of depression amongst the general population in India was found to be 2.6% and 15.1% in 2 different studies [6, 7]. The prevalence of anxiety in a systematic review was found to be between 0.9% and 28.3% in 87 studies across 44 countries [8]. The prevalence of anxiety in India was found to be around 1.6% [9].

Both anxiety and depression affect the patients’ perception of their current health status [2]. Patients with anxiety and depression may have inflated disease activity scores (DAS) by providing increased swollen and tender joint counts in the absence of active disease, thus complicating the management of the disease. The effect may be due to increased pain perception in these patients leading to higher TJC and patient global assessment [10].

Anxiety and depression have a negative impact on quality (QOL) of life in RA, and identification and treatment of underlying psychiatric morbidity is essential to improve the QOL in these patients [11].

Patients with higher scores of depression have more intense pain, poor compliance with the treatment, worse prognosis, and poor QOL, and the presence of depression should alert the treating physician to treat depression and prevent these factors [12].

Anxiety and depression have a significant effect on the QOL in RA patients, which has been shown in multiple studies. We undertook this study to look at the prevalence of anxiety and depression in RA and its correlation with quality of life, pain, disease activity, and functional status in these patients because there are no studies from India about this topic at present.

Material and methods

The study was conducted in a tertiary care teaching hospital in North India. Patients with disease duration of more than 1 year as per 2010 American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism criteria were included in the study [13].

Patients already on antidepressants and anxiolytics were excluded. Quality of life was assessed by using the World Health Organization Quality of Life (WHOQOL-BREF) Hindi version, which is a patient-administered 26-item questionnaire [14].

The questionnaire assesses the scores in four domains, i.e. physical, psychological, social relationships, and environment, with higher scores (transformed to 0–100) reflecting better QOL. Illiterate patients were assisted by the interviewer to complete the questionnaire. Anxiety and depression were measured by using HADS, which is a 14-item questionnaires with 7 responses each for anxiety and depression with a maximum possible score of 3 for a particular response. A score of up to 7 is considered normal, with scores of 8–10 as borderline abnormal and scores 11–21 as being abnormal [15].

Higher scores indicate more severe anxiety and depression. Pain was measured by 100-millimetre Visual Analogue Scale (VAS). The disease activity was measured by Disease Activity Score for 28 joints with 3 variables (DAS28-3) i.e. swollen joint count, tender joint count (TJC), and erythrocyte sedimentation rate by Westergren’s method [16].

Swollen and tender joints were assessed by 1 examiner (GS). Functional disability was measured by using the Indian version of the Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ), with higher scores indicating more disability [17].

The physical health domain covers activities of daily living, mobility, pain, discomfort sleep, rest, and work capacity. It includes questions such as:

Do you have enough energy for everyday life?

How well are you able to get around?

How satisfied are you with your ability to perform your daily living activities?

The psychological domain covers body image and appearance, negative feelings, positive feelings, and self-esteem with questions such as:

How much do you enjoy life?

To what extent do you feel your life to be meaningful?

Are you able to accept your bodily appearance?

How satisfied are you with yourself?

How often do you have negative feelings such as blue mood, despair, anxiety, or depression?

The social domain includes personal relationships, social support, and sexual activity with questions such as:

How satisfied are you with your personal relationships?

How satisfied are you with your sex life?

How satisfied are you with the support you get from your friends?

And the environmental domain covers financial resources freedom, physical safety and security, health and social care: accessibility and quality, home environment, participation in and opportunities for recreation/leisure activities, and transport. The questions in this domain include:

How safe do you feel in your daily life?

How healthy is your physical environment?

Do you have enough money to meet your needs?

To what extent do you have the opportunity for leisure activities?

How satisfied are you with your access to health services?

How satisfied are you with your transport? [14].

The study protocol was approved by the Institution Ethics Committee. IEC/Pharma/Thesis/Research/Project/09 /2011/2060/Category-C. All the patients gave written informed consent.

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed using OpenStat software. The normality of the data was assessed by the Shapiro-Wilk test. Student’s t-test was used to analyse the normally distributed continuous variables, and the Wilcoxon sign rank-test was used for variables not normally distributed, i.e. disease duration, HAQ, pain, and social and environmental domains of the WHOQOL-BREF. The χ2 test was used to test for discrete variables. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered significant.

Correlations were calculated between anxiety, depression, and domains of the WHOQOL, DAS28-3, HAQ, pain (VAS), and disease duration. For correlations a p-value < 0.01 was considered significant in view of multiple comparisons. The effect of anxiety and depression on QOL domains, pain (VAS), HAQ, and DAS28-3 was measured by linear regression analysis. Anxiety and depression were taken as independent variables while QOL domains, pain (VAS), HAQ, and DAS28-3 were taken as dependent variables. The higher values of β coefficient suggesting the stronger the effect of independent variables on the dependent variables.

Results

A total of 88 patients were enrolled into the study, of whom 76 were female. The mean age of the patients was 47.7 ±14.6 years, and mean disease duration was 6.9 ±8.4 years. None of the investigated patients were treated with biological drugs. Baseline characteristics of the patients are shown in the Table I.

Table I

Characteristics of the rheumatoid arthritis patients (N = 88)

Possible anxiety and depression with a HADS score of > 7 was seen in 61 (69%) and 68 (77%) of the patients, respectively (Table II, III).

Table II

Comparison of rheumatoid arthritis patients with and without anxiety (n = 88)

Table III

Comparison of rheumatoid arthritis patients with and without depression (n = 88)

There were no significant differences between RA patients with anxiety compared in terms of age and DAS28-3 with patients without anxiety. Although female patients were more likely to report anxiety (Table II).

Patients with anxiety were likely to have a shorter disease duration (6.6 ±6.4 vs. 7.8 ±11.9 years, p < 0.0001), higher HAQ scores (0.9 ±0.7 vs. 0.7 ±0.8, p < 0.001), higher pain level (VAS 53.8 ±26.4 vs. 39.7 ±26.1, p < 0.05) and more often had depression (95% vs. 37%, p < 0.0001) compared to patients without anxiety. Patients with anxiety had significantly lower scores in all 4 domains of the WHOQOL-BREF as compared to patients without anxiety, suggesting poor QOL for patients with anxiety (Table II).

Comparison of rheumatoid arthritis patients with and without depression

There was no significant difference in the age, gender, and DAS28-3 between the patients in the “depression” and “no depression” groups. Patients in the “depression” group had longer disease duration (7.7 ±9.3 vs. 4.34 ±2.8 years, p < 0.001) and higher HAQ scores (1.0 ±0.7 vs. 0.5 ±0.7, p < 0.01) as compared to patients in the “no depression” group, suggesting more disability in depressed patients.

Patients in the “depression” group also had higher pain level (VAS 54.2 ±25.2 vs. 33.5 ±27.3, p < 0.01) and were more likely to have anxiety (85% vs. 15%, p < 0.0001) (Table III). Quality of life scores of the patients in the “depression” group were significantly lower than the patients in the “no depression” group (Table III).

Correlations between anxiety and depression scores and World Health Organization quality of life domains

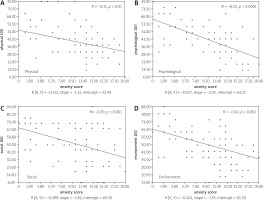

The anxiety score had a negative correlation with all 4 domains of the WHOQOL-BREF, with the psychological health domain showing a strong negative correlation with the anxiety score (r = –0.55, p < 0.0001) (Fig. 1).

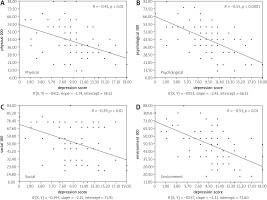

Similarly, the depression score had a negative correlation with all the domains, with the psychological (r = –0.55, p < 0.001) and environment (r = –0.53, p < 0.001) domains showing strong negative correlation with depression scores (Fig. 2).

Correlations between anxiety, depression scores and Disease Activity Score, Health Assessment Questionnaire, pain and disease duration

No significant correlation was found between anxiety scores and DAS28-3 (r = –0.04, p = NS [not significant]), HAQ (r = 0.20, p = NS), pain (VAS) (r = 0.24, p = NS), and disease duration (r = –0.06, p = NS). A significant positive correlation was found between depression score and disease duration (r = 0.30, p < 0.01), while no significant correlation was found between depression scores and DAS28-3 (r = 0.07, p = NS), HAQ (r = 0.13, p = NS), and pain (VAS) (r = 0.12, p = NS).

Effects of anxiety and depression on quality of life and pain, Health Assessment Questionnaire, Disease Activity Score and disease duration

On linear regression analysis anxiety had a significant effect on physical (β = –0.38, p < 0.001), psychological (β = –0.58, p < 0.001), social (β = –0.36, p < 0.001), and environmental domains (β = –0.39, p < 0.001) and pain scores (β = 0.248, p < 0.05). No effect was seen on HAQ, DAS28-3 (Table IV).

Table IV

Linear regression analysis for effect of anxiety and depression on quality of life domains, pain, Health Assessment Questionnaire, Disease Activity Scores

Depression also had a significant effect on all the domains of the WHOQOL-BREF as well as pain (β = 0.44, p < 0.001), HAQ (β = 0.47, p < 0.001), and DAS28-3 (β = 0.22, p < 0.05).

Discussion

In patients with RA the main objective of the treating physicians is improvement in the disease activity parameters measured by various scores such as DAS28-3 or American College of Rheumatology improvement criteria [18].

Underlying mood disorders in the form of anxiety and depression may be the reason for persistent pain despite the control of disease activity with drugs. Diagnosis of the underlying mood disorder and its treatment may be necessary for the control of pain and improvement in the QOL of the patient [19]. Because there is a relationship between severity of depression and disease activity, treatment of depression may lead to improvement in the care of RA patients [20].

About three-fourths of the patients had HADS score > 7, suggesting the presence of possible depression and anxiety in our study. Although this appears to be a high number, similar results have been seen in other studies. The reason for a high prevalence in our study could be the use of HADS as an instrument where a score of more than 7 is taken as a cut-off for abnormal results.

Another reason could be lack of social support in our patients, who were predominantly females (86%).

A study from Egypt reported a high prevalence of anxiety (70%) and depression (66.2%) in RA patients using Research Diagnostic Criteria for the ICD-10 [4]. Depression was associated with functional disability, social stress, and morning stiffness. Anxiety was associated with depression in these patients [4].

An Iranian study reported the presence of depression in 63% and anxiety in 84% of RA patients. Both anxiety and depression were associated with higher pain perception and increased functional disability [21].

Around 62% and 60% of patients had depression and anxiety, respectively, in a Chinese study that used the Hamilton Depression Scale and Hamilton Anxiety Scale. Both anxiety and depression were associated with higher disease activity [22].

A study from India in fibromyalgia patients also reported high levels of anxiety (87%) and depression (72%), and patients with anxiety and depression had poor QOL, more pain, and disturbed sleep [23]. We found that depression besides affecting all the domains of QOL significantly affected pain, functional status and disease activity in our patients. This has been seen in multiple previous studies [4, 19–22].

Depression affects the RA patient in multiple ways. Patients with underlying depression are more likely to have poor QOL, poor compliance with medications, decreased pain threshold, and increase pain perception. Depression in RA is also associated with poor sleep and fatigue, increased risk of suicide, and increased risk of death [24].

Also, patients with depression tend to have poor functional status, and any improvement in depression may lead to improvement in the functional status of the patient [25]. A Dutch study revealed that the fluctuations in the level of depression were associated with the fluctuating levels of functional status of RA patients [26]. Anxiety is usually a known accompaniment of depression and poses diagnostic and therapeutic challenges [27, 28].

In our study anxiety was also found to be a significant co-morbidity in RA patients, and it was more likely to be found in females. Patients with anxiety were more likely to be depressed and had more pain. Both anxiety and depression had significant negative correlation with all the domains of the WHOQOL-BREF, i.e. physical health, psychological, social relationships, and environmental domains.

Studies have shown that anxiety and depression when present in RA patients may lead to poor QOL, increased risk of suicide, and poor prognosis of the disease [29]. The relationship between depression and RA appears to be bidirectional, and the clinical guidelines suggest diagnosing and managing mental health and depression in chronic medical conditions like RA to improve treatment outcomes [20].

Mood disorders in the form of anxiety and depression are quite common in RA patients [1–4]. Usually the treating physicians or rheumatologists are focused on treating arthritis and achieving low DAS28-3 scores. This pushes the underlying mood disturbances into the background.

In a study from Pakistan the diagnosis of clinical depression was missed in 47% of patients with RA who had been under regular follow-up at a tertiary care hospital. Only 18% of those diagnosed with depression were willing to seek referral to a psychiatrist for management of depression [30].

The undiagnosed anxiety and depression may lead to less than satisfactory outcomes even when the joint disease is satisfactorily controlled with drugs [10, 21]. Patients with depression or anxiety may still complain of pain despite having good control of synovitis [19, 20].

Because all the patients visiting the rheumatology clinic are assessed for disease activity and extraarticular manifestations at each visit, they need to be assessed for underlying psychiatric morbidity. Because most of the questionnaires for anxiety and depression are self-assessment questionnaires, these can be handed over to the patients in the waiting areas and the scores noted down in the patients records so that any change in the mood disorder be picked up and the patient be referred to mental health specialists for confirmation of the diagnosis and further management.

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale is a self-assessment questionnaire that serves only as a screening tool for anxiety and depression, and the definite diagnosis depends upon clinical assessment of the patient. With a cut-off of 7, a score of 8–10 is suggestive of an underlying mood disorder, and a score of 11 or more suggests probable presence of mood disorders [31].

Study limitations

Our study also had some limitations. There was no control group to compare the prevalence of anxiety and depression of our patients with the normal population. As this is a cross sectional study, we were only able to capture the data at a single time point in the disease process of the patient.

Studied patients were recruited from the outpatient department of a tertiary care center, which usually takes care of patients with higher disease activity. In the presented analysis a mean DAS28-3 score was 4.6 ±1.3 range (2.1–7.8), which suggests that most of the patients had a moderate activity of the disease (DAS28-3 score between 3.2 to ≤ 5.1) [32]. It means that this sample of the patients may not be representative for all the patients with RA seen in primary and secondary care.

Conclusions

In our study, we found a high prevalence of probable anxiety and depression in RA patients. Higher anxiety scores were associated with more intense pain and lower QOL in all the domains. Higher depression scores were associated with more pain, anxiety, poor functional status, and lower QOL in all the domains.

Both anxiety and depression scores had a negative correlation with all the domains of the WHOQOL-BREF. Both anxiety and depression had negative effects on psychological and environmental domains, and pain in RA patients.

Mood disorders in the form of anxiety and depression are common in RA patients and these have an impact on multiple parameters of the disease like pain, disease activity, QOL, and functional status of the patients. The assessment of the mental health of RA patients should be included in the routine assessment of the patients similar to the assessment of DAS28-3 at each visit. There is important that any changes in mental health could have been detected earlier and the patient will have a possibility to be assessed by a psychiatrist for establishing the diagnosis and further management.