Introduction

Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA) is considered an orphan disease, characterized by granulomatous inflammation, eosinophil-rich infiltration, and systemic necrotizing vasculitis affecting small to medium-sized vessels [1]. The most characteristic clinical feature of EGPA is the occurrence of late-onset bronchial asthma, accompanied by blood and tissue eosinophilia [2]. In approximately 50% of patients, additional anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) are detected, directed mainly against myeloperoxidase (MPO). However, in a significant subgroup of patients, ANCA is absent, and eosinophils play a key role in driving the disease process, rather than ANCA-associated vasculitis. This highlights the key role of eosinophils in the ANCA-free form of EGPA [3].

These different mechanisms contribute to the broad spectrum of clinical manifestations, resulting in a variety of clinical phenotypes [4]. Eosinophilic infiltrates are most frequently located in the lung tissue, the heart, causing cardiomyopathy, and the gastrointestinal tract [1]. In contrast, in patients with MPO-ANCA, a vasculitic phenotype predominates, characterized by palpable purpura, peripheral neuropathy, rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis, and, less frequently, alveolar hemorrhage [1].

Due to its rarity, research into EGPA pathogenesis remains limited, which in turn hinders the optimization of patient outcomes [3, 4]. In this narrative review, we explore the current understanding of EGPA pathogenesis and discuss emerging therapeutic strategies relevant to its management.

Material and methods

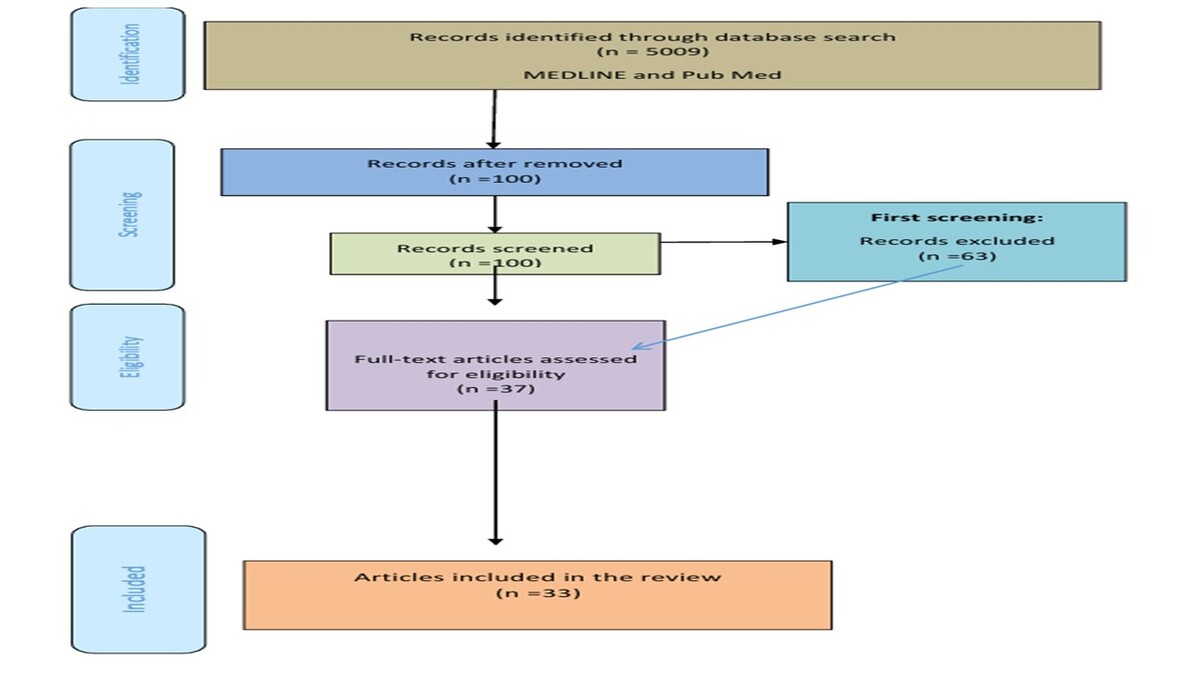

The authors analyzed MEDLINE and PubMed medical databases until April 2025 using the following key words: “eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis”, “EGPA”, “treatment anti-IL-5” (Fig. 1).

Results

Pathogenesis of eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis

Because both innate and adaptive immunity are impaired in EGPA, the disease is considered an immune-inflammatory disease. This includes abnormalities in T and B lymphocytes, as well as eosinophils and neutrophils. In addition, genetic predisposition has been identified as a contributing factor [1, 5–7].

The role of T cells

In EGPA, the disease is characterized by elevated T helper (Th) 2-related cytokines (interleukin-3 [IL-3], IL-4, IL-5, IL-9, IL-10, IL-13, and IL-25), as well as a restricted T-cell receptor repertoire, indicating an antigen-driven activation process [1, 5].

T helper 17 cells are specific lymphocytes producing proinflammatory cytokines (IL-17A, IL-17F, and IL-22), and their function is regulated by T regulatory cells (Treg), which suppress the immune response and play a protective role in autoimmune disease development [5]. Moreover, Th17 lymphocytes promote neutrophil recruitment and activation, which contributes to eosinophilic inflammation and tissue damage [1]. Interestingly, the Th17/Treg ratio correlates well with disease activity markers, suggesting its potential utility as a biomarker of disease progression and response to therapy [5]. The involvement of the Th1 pathway in EGPA is reflected by increased serum concentrations of interferon γ (IFN-γ), a cytokine that not only promotes granuloma formation but also activates CD8+ T cells [1]. These cytotoxic CD8+ T cells contribute to vascular damage, highlighting the complex interplay between Th1-driven immune responses and the pathogenic role of CD8+ T cells in EGPA [5].

The significance of eosinophilia in eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis

Eosinophils were first described by Paul Ehrlich in 1879. They are cells released into the peripheral blood in a phenotypically mature state and are capable of activation and recruitment to tissues in response to appropriate stimuli. These activations mainly include IL-5 and chemokines. The half-life of eosinophils is relatively short, so they spend only a few hours in the peripheral blood (approximately 18 h) and then migrate to the thymus or gastrointestinal tract, where they remain in homeostatic conditions. Relatively few mature forms of eosinophils (less than 400 per mm³) are found in the peripheral blood. In response to inflammatory stimuli, a reaction occurs in which eosinophils develop from advanced bone marrow progenitors. These cells then leave the bone marrow, migrate to the blood, and accumulate in peripheral tissues, where their survival is prolonged [8]. This unique eosinophil biology is defined by key receptors, including the IL-5 receptor subunit (IL-5Rα), CC chemokine receptor 3 (CCR3), sialic acid-binding immunoglobulin-like lectin 8 (SIGLEC-8) in humans, and SIGLEC-F (also known as SIGLEC-5), as well as pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) [8].

Thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP; a cytokine belonging to the IL-2 family), IL-25 (also known as IL-17E; produced mainly by activated TH2 cells and mast cells), and IL-33 (from the IL-1 family of cytokines), and subsequent initiation of IL-5 production promote eosinophils. Activated eosinophils may contribute to the development of EGPA through three unique mechanisms: cytotoxicity, inflammation, and non-immunological effects [9–14].

The increased production of cytokines, such as IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13, by T lymphocytes leads to an increase in eosinophil numbers during active EGPA. C-C chemokine ligand 17 (CCL17; also known as thymus and activation-regulated chemokine – TARC), a chemokine that recruits Th2 cells to tissues, is elevated in serum and biopsies of patients with EGPA and is positively correlated with peripheral blood eosinophil and immunoglobulin E (IgE) levels [15]. This increased Th2 cell activity likely contributes to the development of eosinophilia. Furthermore, blood eosinophils exhibit an activated phenotype, characterized by high levels of CD69 and CD11b, in EGPA. Increased levels of IL-25, a cytokine that influences the production of IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13, are also observed, leading to enhanced production. Interleukin-25 is also detectable in eosinophils in biopsies of skin lesions in EGPA. T cells in these biopsies and blood express the IL-25 receptor, IL-17RB. This suggests a positive feedback loop between Th2 cells and eosinophils in EGPA [6, 16].

Interestingly, several clinical studies and pharmacovigilance reports suggest that anti-leukotriene receptor antagonists (such as montelukast), used in asthma therapy, may unmask or trigger new-onset EGPA [17–19]. According to case-crossover and observational studies, the risk of clinically overt EGPA has been reported to increase by approximately 4.5 times within the first three months of anti-leukotriene treatment initiation, particularly in patients without concurrent glucocorticosteroid (GC) use [17]. This supports the hypothesis that in predisposed individuals, eosinophilic inflammation induced or sustained by leukotriene pathway blockade may contribute to disease development [17, 18].

The significance of interleukin-5 in eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis

Interleukin-5 is a four-helix protein produced mainly by Th2 lymphocytes, as well as by ILC2 (innate lymphoid cells type 2) [20].

The initiation of the signaling cascade begins with the binding of IL-5 to IL-5Rα. In EGPA, this interaction triggers various intracellular signaling pathways that promote eosinophil activation, survival, and proliferation, which play a key role in the development and maintenance of eosinophilia [21].

In humans, IL-5Rα is expressed mainly on the surface of eosinophils and basophils [21]. Although agents targeting the IL-5 ligand are in development, they can only partially reduce the number of eosinophils in the blood and mucosa [22–24].

The role of B cells, anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, and neutrophils

In anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-positive EGPA, neutrophils and B cells are crucial contributors to disease development [1, 5, 7]. Inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF), IL-1β, and C5a prime circulating neutrophils, which then expose ANCA antigens on their surface [7]. This enables the binding of circulating ANCA, activating neutrophils through FcγRIIa and FcγRIIIb receptors [7]. Activated neutrophils release reactive oxygen species (ROS) and cytotoxic enzymes, and form neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), causing vascular damage [1, 7]. Prolonged exposure to MPO from NETs further stimulates B cells to produce ANCA, creating a self-perpetuating cycle [5, 7].

Genetic factors influencing eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis

Immunogenetic factors play a significant role in the predisposition to EGPA pathogenesis [4]. A genome-wide association study (GWAS) revealed that EGPA is driven by multiple genetic factors, with differing profiles depending on ANCA status [25]. These associations indicate disruptions in pathways related to eosinophil activity, asthma, and vasculitis, enhancing our understanding of EGPA’s development and clinical variability [4, 25].

Lyons et al. [26] identified 3 significant genetic loci in EGPA: HLA-DQ, a region near the BCL2L11 gene on chromosome 2, and another near the TSLP gene on chromosome 5 [7, 25]. Furthermore, a pleiotropy-informed analysis highlighted additional genetic associations involving IRF1, IL5, BACH2, LPP, and CDK6, all linked to immune regulation and eosinophil function [25, 27]. In the MPO-ANCA-positive subgroup, an association was found at rs78478398 on chromosome 12, while variants near GPA33 and IRF1/IL5 were specific to the ANCA-negative subset. Notably, genetic links at BCL2L11, TSLP, CDK6, and LPP were independent of ANCA status [25].

The EGPA-linked variant located within an intron of the ACOXL gene, close to BCL2L11 – which encodes the pro-apoptotic protein BIM – is critical for apoptosis and immune system regulation [25]. This variant overlaps with MIR4435-2HG, commonly called MORRBID, a long regulatory RNA molecule regulating eosinophil apoptosis, potentially dysregulated in hypereosinophilic syndrome [25]. Key variants include rs9290877 in the LPP gene, linked to asthma and allergy, suggesting its role in eosinophil recruitment [25]. Additionally, variants such as rs11745587 contribute to increased EGPA risk and elevated eosinophil numbers, whereas those near GATA3 influence Th2 lineage commitment, facilitating eosinophilic inflammation via secretion of cytokines including IL-5, IL-4, as well as IL-13 [25]. In addition, variations in the IL-10 gene promoter have been linked to an overall susceptibility to EGPA, while IRF1/IL5 and GPA33 variants specifically correlate with the MPO-ANCA-negative form of the disease [1]. Notably, both IL-10 and IRF1/IL5 play roles in eosinophilic inflammation, with IL-10 being key for activating the Th2 pathway and IRF1/IL5 influencing the regulatory regions of IL-4 and IL-5, which are crucial for eosinophil recruitment and function [1, 28]. Research on candidate genes in EGPA cohorts has identified associations with HLA-DRB4 and DRB107, while DRB3 and DRB113 may have a protective effect [1, 5, 6]. Certain HLA alleles, such as DRB1, DRB4, DQA1, and DQB1, are linked to an increased likelihood of developing vasculitis associated with the disease [25, 29].

Treatment, prognosis, and long-term outcomes

Due to the complex pathophysiology of EGPA described above, the treatment of this disease entity remains a significant challenge for clinicians. In clinical practice, we rely on the latest 2023 recommendations for the treatment of EGPA. These guidelines are based on evidence regarding the diagnosis and treatment of EGPA [30]. These recommendations consist of 7 statements (Table I) describing the therapeutic procedure in individual forms of EGPA.

Table I

Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis treatment recommendations, based on [27]

The goal of treatment is to achieve remission, which in EGPA is defined as the absence of clinical symptoms attributed to active disease, including asthma and ear, nose and throat (ENT) symptoms. The daily dose of GCs is also taken into account. The maximum daily dose in this case is 7.5 mg of prednisone per day. A relapse in EGPA is when clinical symptoms attributed to active disease return after a period of remission, when the dose of GCs needs to be increased, or when the dose of disease-modifying drugs is started or increased. It is essential to distinguish between a relapse or new onset of systemic vasculitis (systemic relapse) and an isolated exacerbation of asthma and ENT symptoms (respiratory relapse).

The IL-5-targeted agent mepolizumab may be considered for severe disease or for induction in refractory non-severe EGPA to maintain remission [30]. Other IL-5-targeted agents have also shown promising results in maintaining remission in EGPA. These include benralizumab, a fully humanized monoclonal antibody that binds with high affinity to the IL-5 receptor α chain, and reslizumab, an IL-5 monoclonal antibody [31–34]. A recent study also showed that benralizumab was noninferior to mepolizumab in inducing remission in patients with EGPA. Both treatments reduced eosinophil counts throughout the entire follow-up period, although a greater reduction was seen in the benralizumab group at all time points [25, 35]. Complete discontinuation of oral GCs was achieved in 41% of patients receiving benralizumab and 26% of patients receiving mepolizumab at weeks 48 to 52. We also know that, in addition to IL-5, various other factors modulate eosinophil survival at the site of inflammation. This means that selective inhibition of only IL-5 activity may result in delayed and incomplete blockade of eosinophils [12, 36]. Benralizumab exerts a pronounced, direct effect on eosinophils by directly binding to the IL-5 receptor on the cell surface. Furthermore, the removal of a fucose residue from the Fc region of benralizumab increases its binding affinity for the Fc γ III-A (FcγIIIA) receptor present on cytotoxic and phagocytic cells, which mediate the antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity response [37].

Pulse intravenous GC therapy (usually daily pulses of methylprednisolone 500–1,000 mg for 3 days, to a maximum total dose of 3 g) followed by high-dose oral GCs (e.g., 0.75–1 mg/kg/day) is recommended for patients with severe disease [30]. Adding cyclophosphamide to GCs to induce remission should be considered in patients with severe disease. The optimal duration of cyclophosphamide induction therapy in severe EGPA has not yet been established. The recommendation is that cyclophosphamide induction therapy should be continued until remission is achieved, as in other small vessel vasculitides, typically for 6 months. More extended induction periods (up to 9–12 months) are recommended for patients who show slow improvement and do not achieve complete remission by the end of month 6. Rituximab may be particularly effective in treating recurrent EGPA vasculitis [38], which represents an additional therapeutic option.

The definition of refractory EGPA is unchanged or increased disease activity after 4 weeks of appropriate remission-induction therapy. Persistence or worsening of systemic symptoms should be distinguished from respiratory symptoms.

There are no reliable biomarkers for measuring disease activity in EGPA, although some laboratory parameters (e.g., eosinophil count or ANCA) are commonly monitored. Therefore, disease activity should only be assessed during follow-up, using validated clinical tools [30]. As with other vasculitides, routine monitoring of EGPA-related symptoms is recommended, with particular attention paid to pulmonary involvement, cardiovascular risk, and neurological complications. Long-term monitoring of comorbidities (such as cancer, infections, and osteoporosis) is also recommended [30].

Conclusions

This study provides significant and comprehensive insights into the complex pathogenesis of EGPA. As treatment options continue to evolve, particularly biologic therapies, drugs targeting the IL-5 receptor offer a more tolerable and effective GC-sparing approach, representing a significant advance in treatment strategies.