Introduction

Infrared thermography (IRT) is a non-invasive imaging technique that captures a two-dimensional representation of skin surface temperature, which reflects underlying blood flow and microcirculatory function. Since skin temperature correlates closely with local perfusion, IRT serves as an indirect yet valuable tool for evaluating vascular health. This technology enables the assessment of vascular reactivity under resting conditions as well as in response to thermal or pharmacological stimuli [1, 2].

Initially developed for military applications during and after World War II, infrared imaging technology gradually transitioned into industrial and civilian use by the late 1950s. Over the past few decades, substantial advances in camera design – particularly the shift from bulky, nitrogen-cooled devices to compact, user-friendly, and commercially accessible systems – have significantly broadened its applications, including in the field of medicine [3].

In recent years, medical imaging has seen rapid progress, particularly in the development of non-invasive tools to assess vascular disorders such as Raynaud’s phenomenon (RP) [4, 5]. Raynaud’s phenomenon is a vascular disorder characterized by episodic vasospastic attacks of the digital arteries, arterioles, and cutaneous vessels, most often precipitated by exposure to cold temperatures or emotional stress. According to the 2017 European Society of Vascular Medicine guidelines [6], diagnosis requires an initial well-demarcated pallor (white phase) followed by cyanosis (blue phase) in the affected digits, reflecting sequential vasoconstriction and deoxygenation. These transient, reversible ischemic episodes can affect the fingers, toes, and other acral regions. Raynaud’s phenomenon may be idiopathic (primary RP – PRP) or secondary (SRP) to underlying conditions such as autoimmune rheumatic diseases (e.g., systemic sclerosis [SSc], systemic lupus erythematosus [SLE]), medication use, or occupational exposures – particularly chronic hand-arm vibration. Differentiating between PRP and SRP is clinically important, as SRP may indicate significant underlying pathology and warrants targeted investigation and management [7–10].

While cold provocation testing was historically used to confirm RP, it is no longer recommended in routine clinical practice. Current diagnostic evaluation relies primarily on a detailed medical history and physical examination, with patient-provided photographs of vasospastic episodes serving as valuable adjuncts. The most recent consensus criteria, proposed by Maverakis et al. in 2014 [11], outline a three-step diagnostic process that does not include cold provocation testing, emphasizing clinical assessment to distinguish PRP from SRP and to guide further investigation. Although RP is often diagnosed on the basis of history, examination findings, and supportive laboratory results, its presentation may occasionally be complex. For example, in vibration white finger (VWF) – a form of SRP caused by chronic occupational exposure to hand-arm vibration – a confirmed diagnosis is important not only for clinical management but also for medico-legal recognition as an occupational disease. In such cases, continued exposure may aggravate the condition, making occupational modification essential to prevent further vascular injury [12, 13].

Due to the episodic nature of RP, direct observation of an attack by a clinician or patient-provided photographic evidence can aid in diagnosis, though these are not always practical. Consequently, objective tests such as cold provocation tests are often employed to reproduce symptoms and verify the diagnosis in a controlled setting [14–16].

Raynaud’s phenomenon is broadly classified into 2 types: PRP, which occurs independently without association with any systemic illness and accounts for nearly 80% of cases, and SRP, which is linked to underlying connective tissue disorders such as SSc, mixed connective tissue disease, and SLE [17].

In the pediatric population, RP affects approximately 15% of children, with a higher prevalence among females and increasing incidence with age [18, 19]. According to studies, about 70% of RP cases in children are primary. Among secondary causes, SSc is the most commonly associated connective tissue disease and is frequently the initial clinical manifestation, reported as the first symptom in 61–70% of pediatric patients diagnosed with SSc [20, 21].

Infrared thermography has emerged as a promising technique for both clinical evaluation and research purposes. Notably, it offers several key advantages:

Differentiation of RP subtypes: Differentiating PRP from SRP is clinically important, as SRP often signals an underlying connective tissue disease. Nailfold capillaroscopy (NFC) remains the gold standard for this distinction, enabling direct visualization of the microvascular architecture. In PRP, capillary morphology is typically normal, whereas SRP – particularly in SSc – shows characteristic abnormalities such as capillary dilatation, dropout, avascular areas, and microhemorrhages. Recent studies and consensus guidelines recommend NFC as a first-line investigation for all patients presenting with RP, given its high sensitivity and specificity for detecting early microangiopathy and enabling timely diagnosis and intervention. Infrared thermography, which assesses skin temperature as a surrogate for peripheral blood flow, offers complementary functional information by detecting vasospastic episodes and revealing differences in peripheral perfusion between PRP and SRP. However, unlike NFC, IRT cannot visualize structural microvascular changes, limiting its ability to detect early morphological abnormalities. A combined approach – using NFC for structural assessment and IRT for functional evaluation – may enhance diagnostic accuracy and optimize patient management [22–24].

Objective monitoring of disease and therapy: The use of IRT allows for quantifiable, reproducible assessment of disease severity and treatment response. This is particularly important in the context of clinical trials, where the need for sensitive and reliable outcome measures is critical. Currently, the Raynaud’s Condition Score is the only validated outcome measure, yet it remains subjective. Infrared thermography holds potential as a more objective and sensitive alternative [22].

As research into RP continues to advance, IRT has emerged as a promising tool not only for diagnostic evaluation but also for monitoring treatment response. Its ability to visualize and quantify microvascular dynamics provides unique insights into the pathophysiology of RP. Recent studies have demonstrated encouraging predictive capabilities, with some models achieving a sensitivity of 82% and a negative predictive value of 93%, comparable to previous thermographic investigations [25, 26]. However, despite growing evidence supporting its clinical utility, the lack of standardized imaging protocols and methodological consistency has hindered its broader adoption in routine practice. This review aims to provide a comprehensive evaluation of the current evidence regarding the use of IRT in RP, comparing its diagnostic performance with existing modalities and emphasizing its potential in distinguishing between primary and secondary forms. By synthesizing findings from contemporary research and clinical trials, this article endeavors to clarify the strengths and limitations of IRT, while outlining its future role in enhancing diagnostic accuracy and therapeutic monitoring within rheumatological care.

Search strategy and methodology

A comprehensive literature search was conducted to identify relevant studies on the clinical application of IRT in the diagnosis and monitoring of RP. The search included both primary databases such as MEDLINE/PubMed (2010 – present), Scopus, Web of Science, Embase, and secondary sources including Google Scholar, PubMed Central, and ScienceDirect.

The search strategy incorporated a combination of free-text terms, Boolean operators (AND/OR), and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) to ensure the retrieval of all relevant literature. Key search terms included: “Raynaud’s phenomenon,” “primary Raynaud’s,” “secondary Raynaud’s,” “systemic sclerosis,” “connective tissue disease,” “vascular disorders,” “digital ischemia,” combined with: “infrared thermography,” “IRT,” “thermal imaging,” “thermographic assessment,” “digital rewarming,” and “cold challenge test.”

Medical Subject Headings terms were used to enhance search precision, including: “Raynaud Disease,” “Thermography,” “Vasospasm, Raynaud,” “Systemic Sclerosis,” “Microcirculation,” and “Vascular Imaging.”

In addition to database querying, references from selected articles and previous systematic reviews were hand-searched to ensure inclusion of relevant and recent data not captured during the initial search.

The selection process followed the PRISMA 2020 guidelines. After initial title and abstract screening, full texts were reviewed for relevance.

Inclusion criteria were:

original research articles (clinical trials, observational studies, cross-sectional studies),

studies using IRT for diagnosis, classification, or monitoring of RP,

studies comparing IRT with other diagnostic modalities (e.g., finger systolic pressure test, capillaroscopy, Doppler imaging),

articles published in English between 2010 and 2025.

Exclusion criteria included:

editorials, conference abstracts, narrative reviews,

case reports lacking objective IRT data,

non-English publications.

Data extraction focused on study characteristics (population, protocol), diagnostic accuracy (sensitivity, specificity), outcome measures, and comparisons with other diagnostic tools. Two independent reviewers performed article selection and data extraction. Disagreements were resolved through discussion or third-party arbitration.

Physical and physiological principles of infrared thermography

Infrared radiation (IR) occupies a segment of the electromagnetic spectrum with wavelengths longer than visible light, typically ranging from 700 nm to 1 mm. According to the Stefan-Boltzmann law, all objects emit IR radiation, and the intensity of this emission is directly proportional to the fourth power of the object’s absolute temperature (in kelvins). Simply put, the warmer an object, the greater the amount of thermal radiation it releases. Infrared thermography capitalizes on this principle by enabling the visualization and quantification of thermal emissions. This provides valuable insights into the temperature distribution across a surface, such as the human body, allowing the detection of abnormal thermal patterns that may reflect underlying physiological or pathological processes [27].

In the human body, the average core temperature is approximately 37 ±0.5°C. However, the skin surface temperature is generally lower and subject to variability due to environmental and internal factors. Numerous pathological states can cause deviations in thermal emission. For instance, localized increases in temperature may occur with inflammation, infection, trauma, or malignancies, while reduced temperature may suggest impaired perfusion or ischemia. Because these thermal changes can precede structural changes detectable by traditional imaging methods, IRT offers potential for early identification of various medical conditions [28].

Nevertheless, it is important to recognize that human body temperature is influenced by numerous physiological and external factors. Variables such as age, circadian rhythm, seasonal variation, emotional state, physical activity, hormonal fluctuations, and certain medications can all affect thermal readings. Therefore, interpretation of thermographic images must be performed carefully, in conjunction with clinical findings and results from other diagnostic tools, to ensure accurate and meaningful conclusions [29].

Thermographic devices: manufacturers, technical specifications, and imaging standards

A comprehensive scoping review conducted by Kesztyüs et al. [30] assessed 72 studies that employed a range of thermographic devices from various manufacturers, revealing significant variability in technical specifications and procedural rigor. In total, 69 unique camera models were reported, with FLIR Systems being the most frequently used – appearing in over half of the investigations. This predominance highlights FLIR’s leading role in clinical thermography applications, particularly in studies focusing on vascular and microcirculatory disorders such as RP [30].

The most frequently used camera models across these manufacturers include:

FLIR Systems: E-series (E60, E75), T-series (T640, T530), SC-series (SC5000) [31],

Nippon Avionics: Thermo Tracer TH9100 and TH9260 series [32, 33],

AGEMA: 570 and 880 series (historically popular prior to FLIR acquisition) [36],

FLUKE: TiX560 and Ti400 thermal imagers [37],

MEDITHERM: Med2000 system [36],

OPGAL: Therm-App and EyeCGas series [38].

The thermal resolution of devices ranged from 48 × 47 to 1,024 × 678 pixels, with a median resolution of 320 × 240 pixels. Thermal sensitivity varied from < 0.02°C to 0.5°C, with a median of 0.07°C, while accuracy values spanned ±0.2°C to ±5°C. Notably, for some models, accuracy data were reported only in percentages or not at all, limiting interpretability (Fig. 1).

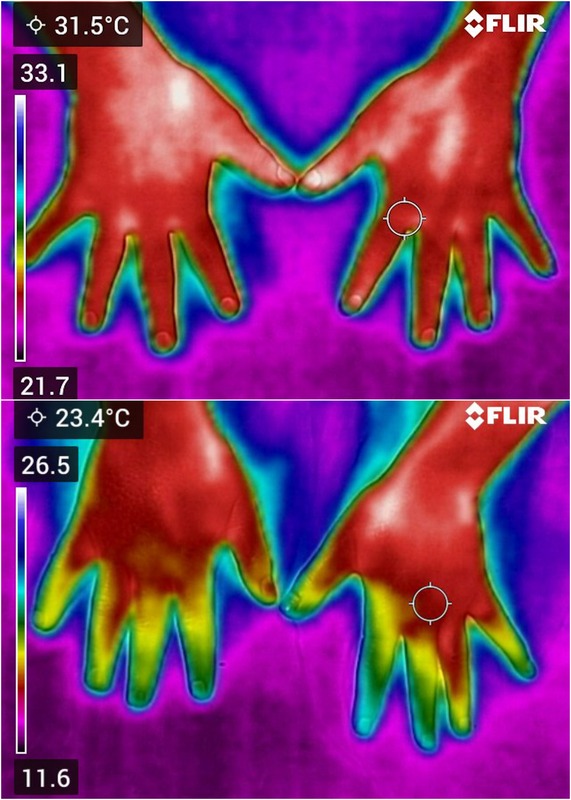

Fig. 1

A) Infrared thermographic image of a healthy control subject, acquired under resting conditions using a FLIR C5 camera. B) Infrared thermographic image of a patient with RP, acquired under resting conditions using a FLIR C5 camera.

Despite technological advancements, the reliability and reproducibility of thermographic measurements remain highly contingent on several factors:

environmental stability,

camera performance and calibration,

patient preparation and positioning,

operator expertise.

The need for standardized imaging protocols was recognized early on. Ring and Ammer [39] emphasized the importance of harmonized procedures encompassing environmental conditions, patient management, imaging execution, and post-processing. These principles were later reinforced by the International Academy of Clinical Thermology, which released quality assurance guidelines in 2015 [39]. Adherence to such standards is essential to ensure valid and reproducible thermographic assessments in clinical research and routine diagnostics.

This variability underscores the urgency for adopting uniform operating protocols and investing in technological calibration and operator training, particularly when IRT is to be used as a diagnostic or monitoring tool for RP in clinical rheumatology.

Clinical applications and use trends of infrared thermography

Infrared thermography has been used in medical diagnostics for over five decades, with its earliest applications in oncology, particularly for detecting breast cancer and malignant melanoma. Over time, its use has expanded across a range of clinical conditions, including monitoring therapy response in inflammatory arthritis, assessing musculoskeletal injuries, identifying tender points in fibromyalgia, diagnosing complex regional pain syndrome, and evaluating microvascular function in vascular disorders [40].

A recent scoping review identified four primary purposes for IRT in clinical research: screening (41.7%), monitoring (26.4%), diagnosis (23.6%), and establishing normative data (8.3%). This highlights IRT’s predominant role as a screening tool, particularly valuable for early detection through its ability to capture physiological changes before anatomical manifestations [30]. Clinically, the most frequent applications of IRT are in oncology, infectious diseases, rheumatology, endocrinology, ophthalmology, and orthopedics. Other areas such as cardiology, neurology, wound care, and trauma medicine also show emerging use. A notable increase in research activity has occurred in recent years, peaking between 2019 and 2021, reflecting growing interest fueled by advancements in thermal imaging technology [25].

Despite its broad potential, the routine clinical adoption of IRT remains limited due to a lack of standardized imaging protocols and the relatively low availability of high-resolution thermal equipment. Addressing these challenges is essential to enable more consistent and effective integration of IRT into mainstream clinical practice.

Diagnostic application of infrared thermography in Raynaud’s phenomenon

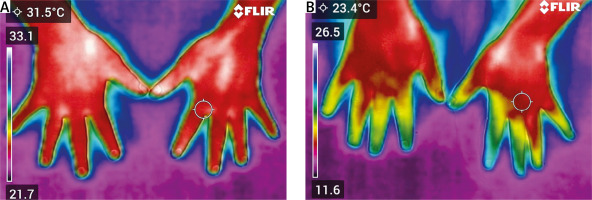

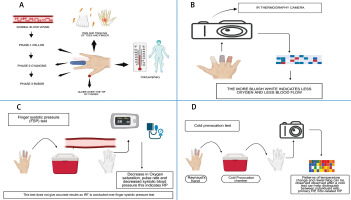

Infrared thermography has emerged as a valuable diagnostic tool in RP, offering a non-invasive means to assess peripheral microvascular function and differentiate between primary and secondary forms of the condition (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2

Composite visual representation of clinical features and diagnostic modalities in RP using IRT (created in BioRender by Patil H. (2025) https://BioRender.com/9nwcr29). A) Clinical manifestations of RP. This panel illustrates the triphasic color changes characteristic of RP: Phase 1 – pallor: due to vasospasm causing reduced blood flow (ischemia); Phase 2 – cyanosis: accumulation of deoxygenated blood resulting in a bluish hue; Phase 3 – rubor: reperfusion phase with reactive hyperemia and redness. Accompanying symptoms include pain, tingling of digits, cold periphery, and digital ulcers in advanced or SRP. B) Application of IRT, showing a thermographic image where bluish-white color denotes reduced blood flow and oxygenation. C) Finger systolic pressure test procedure and its findings, indicating decreased oxygen saturation and blood pressure as suggestive of RP. D) Cold provocation test protocol, where thermographic monitoring of rewarming patterns after exposure helps differentiate between primary RP and SSc-related SRP.

FSP – finger systolic pressure, IRT – infrared thermography, RP – Raynaud’s phenomenon, SSc – systemic sclerosis.

A study by Martini et al. [41] found IRT to be a reliable and reproducible method (intraclass correlation coefficient [ICC] > 0.93) for assessing peripheral microvascular disturbances in children. Infrared thermography effectively distinguished PRP, SRP, and acrocyanosis through differences in baseline temperatures and rewarming patterns. Primary RP patients showed higher DIP temperatures (29.96°C in PRP vs. 29.31°C in SRP and 25.66°C in acrocyanosis) and smaller distal-dorsal differences (0.56°C in PRP vs. 1.99°C in SRP). After a cold challenge, PRP patients demonstrated faster and more complete temperature recovery [41].

Schuhfried et al. [42] demonstrated that IRT can assist in diagnosing SRP by effectively discriminating between patients with and without definite RP based on the longitudinal temperature difference before the old challenge test (LTDpre). In patients without RP, the thermographic method employing the LTDpre demonstrated a sensitivity of 96% and a specificity of 62%. For those with definite RP, sensitivity was 77% and specificity was 73%. In patients with unlikely or probable RP, sensitivity dropped to nearly zero (5%), while specificity remained high at 100% and 95% [42].

Sternbersky et al. [43] illustrated that IRT serves as a diagnostic tool that can differentiate between healthy patients and those with RP. Lindberg et al. [44] found that at a 0.05 cut-off level, the thermographic algorithm achieved a sensitivity of 65%, specificity of 58%, and accuracy of 66%, demonstrating non-inferiority compared to the finger systolic pressure (FSP) test (sensitivity of 77%, specificity of 37%, and accuracy of 59%). Their findings underscored the utility of thermography in detecting RP and suggested its potential as a replacement for the FSP test in diagnostic settings [44].

The diagnosis of RP often relies on a patient’s medical history and the observation of the characteristic triphasic color changes. However, given the episodic nature of the condition, these signs and symptoms may not be present during a clinical examination [15]. Furthermore, the need to differentiate between the benign primary form and the potentially severe secondary form, as well as to monitor the progression of the disease and the response to various treatments, highlights the critical need for objective diagnostic and monitoring tools. Traditional methods, such as the FSP test, have been described as outdated, cumbersome, and sometimes unreliable. Moreover, patient-reported outcome measures, while valuable for understanding the patient’s perspective, are subjective and susceptible to placebo effects, which can limit their utility as the sole indicators of treatment efficacy [45].

Monitoring, evaluation, and therapeutic applications

Schlager et al. [46] reported IRT as a non-invasive technique to assess skin perfusion and vasoreactivity in RP. They found a strong correlation between IRT and laser Doppler perfusion imaging (LDPI) measurements in both RP patients and healthy controls. At baseline (room temperature), RP patients showed mean fingertip temperatures of 31.2 ±3.7°C, compared to 35.42 ±3.1°C in healthy controls. The correlation was particularly strong in RP patients (ρ = 0.868) compared to healthy controls (ρ = 0.790) [46]. Wilkinson et al. [4] recommended using thermography as a secondary outcome measure in clinical trials, focusing on the area under the curve (AUC) and maximum temperature (MAX) as key parameters for evaluating treatment efficacy. This recommendation was supported by their findings showing substantial test-retest reliability for both thermography measurements (AUC ICC = 0.68; MAX ICC = 0.72) and strong convergent validity with laser speckle contrast imaging (latent correlations: AUC ρ = 0.94; MAX ρ = 0.87) [4].

Coleiro et al. [47] reported that IRT objectively assessed treatment responses in RP, revealing significant improvements in digital rewarming with fluoxetine treatment, especially in females and PRP patients. After fluoxetine treatment, female patients showed significant improvement in rewarming (29.0–44.6%). Patients with PRP demonstrated the most dramatic improvement with fluoxetine, with rewarming increasing from 33.4% to 58.8% (p = 0.03). In contrast, those with SRP showed minimal change (31.6–31.2%) [47]. However, Dziadzio et al. [48] reported that thermography did not demonstrate any significant improvement in vascular response or hand temperature recovery after cold challenge in patients treated with losartan or nifedipine in patients with PRP or RP secondary to SSc.

In RP, where underlying structural damage to the blood vessels exists, the rewarming phase can be even slower and may not result in a complete return to baseline temperatures [45]. As a result, IRT can depict the functional repercussions of RP’s vascular dysregulation by revealing aberrant temperature responses to cold, specifically excessive cooling and delayed or incomplete rewarming in the affected extremities [40].

Several studies have evaluated the diagnostic accuracy of IRT for RP, frequently comparing it to clinical diagnosis or other objective diagnostic techniques (Table I) [40, 44, 49].

Table I

Diagnostic performance of IRT in RP across selected studies. This table summarizes the diagnostic sensitivity and specificity of IRT in RP as reported in 3 key studies. Different protocols and comparison methods were employed, including finger systolic pressure testing and cold stress tests, to evaluate the effectiveness of IRT in detecting RP and differentiating between subtypes

| Author | Population | Protocol | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Comparison method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ture et al. [49] | Primary RP compared with healthy controls | Local cooling (10°C, 1 min) | 82 | 86 | FSP test |

| Lindberg et al. [44] | Suspected RP patients | Local cooling (10°C, 1 min), thermographic algorithm | 69 | 58 | FSP test |

| Ammer et al. [40] | Suspected RP patients | Cold stress test, baseline cold fingers | 78.4 | 72.4 | Cold stress test |

These data indicate that IRT’s diagnosis accuracy for RP is promising, with reported sensitivities and specificities ranging from modest to high, depending on the methodology used and the patient population being studied. This suggests that IRT can be a useful tool in the diagnostic arsenal for RP, although its efficacy is definitely influenced by a variety of factors such as the testing methodology and the characteristics of the individuals being investigated.

Infrared thermography has demonstrated potential in distinguishing between PRP and SRP through assessing baseline skin temperatures and the pattern of rewarming following a cold challenge [45]. In PRP, the rewarming of the fingers following cold exposure is usually delayed as compared to healthy individuals, but it generally returns to baseline values. In contrast to SRP, especially in cases linked with structural microvascular damage such as that observed in SSc, the rewarming process is frequently substantially slower and may remain incomplete. The IRT allows for the indirect assessment of blood flow and has been used to help distinguish between PRP and RP associated with SSc (SSc-related RP). In particular, the distal-dorsal difference (DDD), which represents the temperature difference between the fingertips and the back of the hand, especially when measured at a room temperature of 30°C, has been proposed as a specific thermographic parameter that may help in determining the underlying structural vascular disease characteristic of SRP [30].

Cold provocation tests, which typically entail submerging the hands in cold water, are commonly used in conjunction with IRT to measure the dynamic vascular response. The changes in skin temperature that occur during and after the cold challenge can help to highlight the differences in vascular function between PRP and SRP [50]. The unique patterns of temperature change and rewarming observed after a cold test can help distinguish between individuals with PRP, SSc-related RP, and healthy controls. Parameters generated from the rewarming curve, such as the lag time before rewarming begins, the maximum rate of temperature recovery, and the percentage of temperature recovery at key time points, are very relevant in distinguishing between PRP and SRP. Cold provocation, therefore, serves as a physiological stressor that elicits the characteristic vascular response in RP, making the underlying differences in vascular function between primary and secondary forms more apparent when assessed using thermographic imaging, especially during the critical rewarming phase [30].

The FSP test is another objective approach for assessing RP. It involves measuring digital systolic blood pressure before and after exposure to cold 5. A large decrease in pressure after cooling is indicative of RP. The claimed sensitivity of the FSP test varies greatly (range: 51–92%), whereas the specificity is usually in the range 81–100%. Several studies have demonstrated that IRT performs similarly to or better than the FSP test [51, 52]. For example, one study found that a thermographic algorithm had comparable accuracy to the FSP test in the patient population.

The FSP test is frequently regarded as time-consuming, inconvenient, and uncomfortable for patients because it necessitates specialized and sometimes obsolete equipment 5. In contrast, because of its non-contact nature, IRT is often seen as less technically difficult and more comfortable for patients. Thus, IRT offers a potentially more practical and patient-friendly alternative to the FSP test for objectively assessing RP, with evidence indicating equivalent diagnosis accuracy in specific settings [51].

Limitations of infrared thermography

Although IRT offers several compelling advantages as a non-invasive and functional imaging tool, it is not without limitations. One of the primary challenges lies in the sensitivity of skin temperature to a wide range of external and internal variables. Despite careful patient preparation, unpredictable environmental conditions and physiological fluctuations can influence skin temperature, potentially affecting the reliability of the results. Another concern is the accuracy of temperature measurements. Factors such as ambient humidity, variability in skin emissivity, and the calibration status of the IR camera can introduce inconsistencies in thermal readings. These technical limitations can reduce the precision of thermographic assessments. A significant issue affecting the clinical utility of IRT is the lack of standardized equipment and imaging protocols across different centers. The use of diverse IR devices and methodological approaches leads to variability in data acquisition and interpretation, thereby limiting the reproducibility and comparability of results. This lack of uniformity also hampers the development of robust, evidence-based conclusions. A systematic review by Pauling et al. [53] highlighted this gap, noting the absence of a universally accepted thermographic parameter that could serve as an objective endpoint in clinical trials. Moreover, IRT provides only an indirect assessment of tissue perfusion by visualizing surface temperature changes. In contrast, more advanced techniques such as LDPI and laser speckle contrast analysis offer direct visualization and quantification of microvascular blood flow, delivering more detailed insights into circulatory dynamics [53]. Given these limitations, while IRT remains a useful adjunctive tool in vascular and rheumatologic assessments, its results must be interpreted cautiously and ideally supplemented with other diagnostic modalities for comprehensive evaluation.

Future directions

Despite significant advances in the application of IRT for the assessment of RP, several critical gaps remain that must be addressed to enable its widespread clinical adoption and standardization. The following future directions are proposed to strengthen the diagnostic, monitoring, and therapeutic utility of IRT in RP:

Development of standardized protocols. A universally accepted and standardized protocol for performing, interpreting, and reporting IRT in RP is urgently needed. This includes the harmonization of environmental conditions (e.g., room temperature, acclimatization time), imaging parameters, cold provocation techniques, and thermographic indices such as DDD and rewarming kinetics. Standardization will improve reproducibility, allow for meta-analyses, and facilitate integration into clinical guidelines.

Large-scale, multicenter validation studies. Current evidence is limited by small sample sizes and heterogeneous methodologies. Well-designed, multicenter prospective studies with diverse populations are essential to validate diagnostic accuracy, determine optimal cutoff values for thermographic parameters, and establish normative data across age, sex, and geographic regions.

Integration with multimodal diagnostic approaches. Combining IRT with serological markers, capillaroscopy, and other imaging modalities (e.g., laser Doppler imaging or speckle contrast imaging) may enhance diagnostic accuracy, particularly in distinguishing PRP from SRP and identifying early vascular dysfunction in systemic autoimmune diseases. Multimodal algorithms should be developed and tested for their diagnostic and prognostic performance.

Advancements in portable and artificial intelligence (AI)-enhanced thermography. The emergence of mobile, low-cost thermal imaging devices integrated with AI offers new opportunities for point-of-care screening and remote monitoring of RP. The AI-powered algorithms can assist in pattern recognition, automate quantification of temperature changes, and reduce inter-observer variability. Future research should focus on validating these innovations in clinical and community settings.

Application in therapeutic monitoring and drug trials. Infrared thermography should be more widely adopted as an objective endpoint in clinical trials evaluating vasodilator therapies, biologics, or novel interventions for RP and SSc-related digital vasculopathy. Longitudinal IRT assessments can offer quantitative data on treatment efficacy, disease progression, and flare prediction, thus informing therapeutic decisions.

Customized, risk-based diagnostic algorithms. Future research should aim to build predictive thermographic models tailored to patient risk factors (e.g., connective tissue disease status, digital ulcer history, duration of symptoms). These models can support early detection strategies and personalized medicine approaches in RP management.

Educational initiatives and awareness programs. There is a pressing need for enhanced education of clinicians, allied health professionals, and patients regarding the utility of IRT and the significance of early RP symptoms. Public health initiatives should promote early recognition and referral, particularly in high-risk populations.

Conclusions

This study reinforces the clinical value of IRT in distinguishing primary from secondary RP and in monitoring treatment response. Compared to traditional methods, IRT offers a non-invasive, functional assessment of peripheral blood flow that complements structural evaluation by nailfold capillaroscopy. Our findings highlight the potential of integrating IRT into diagnostic algorithms to improve early detection and management strategies. Future studies with larger, diverse cohorts and standardized protocols are warranted to confirm these results and further define the role of IRT in routine clinical practice.