Introduction

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is a method of treatment of end-stage osteoarthritis (OA) and joint degeneration in inflammatory rheumatic diseases. It is one of the most prevalent and cost-effective surgical procedures in orthopedics [1]. Current registers indicate a continuous increase in the volume of TKA procedures, primarily due to ageing of the population [2]. A significant challenge associated with total knee replacement is blood loss.

In older studies, the average total blood loss after TKA was 1,498 ml [3] and the average drop in hemoglobin (Hb) level was 3.85 g/dl [4]. In more recent papers, these values tend to decrease, e.g., Schmidt-Braekling et al. [5] reported that hypotensive epidural anesthesia and the resulting fluid substitution resulted in an average Hb drop of 2.1 g/dl. Historically, the transfusion rate following TKA was up to 35%. However, with modern perioperative practices, it has decreased to appro ximately 3% [6]. Postoperative anemia results in:

Consequently, the need for allogenic blood transfusion may arise; however, this procedure carries the risk of various complications.

Allogenic blood transfusion increases the risk of superficial wound infection (OR = 1.9, 95% CI: 1.2–2.9, p = 0.005) as well as periprosthetic joint infection after joint arthroplasty (OR = 1.6, 95% CI: 1.1–2.2, p = 0.008) [9]. The mechanism of this phenomenon may be explained by:

Although the complication rates associated with allogenic transfusion are currently low due to improved screening methods, systemic reactions also might arise, including infections, allergic responses, fever, acute immune hemolytic events, transfusion-related acute lung injury, iron accumulation, delayed hemolytic reactions, or graft-versus-host disease [13].

These considerations indicate the need to establish effective and safe bleeding control strategies. Our goal is that bleeding management should target a “zero” allogenic post-operative transfusion rate. The aim of the review is to identify strategies to reduce blood loss during TKA and propose a clinical algorithm.

Material and methods

The literature was searched using PubMed and Google scholar by key terms: “total knee arthroplasty”, “total knee replacement”, “knee osteoarthritis”, “blood loss”, “bleeding”, and “anemia.” Only publications with English language abstracts were included. Preference was given to meta-analyses and systematic reviews published in the last decade. Following an electronic search of the databases, two independent reviewers screened the articles based on their relevance to the review’s objectives.

Results

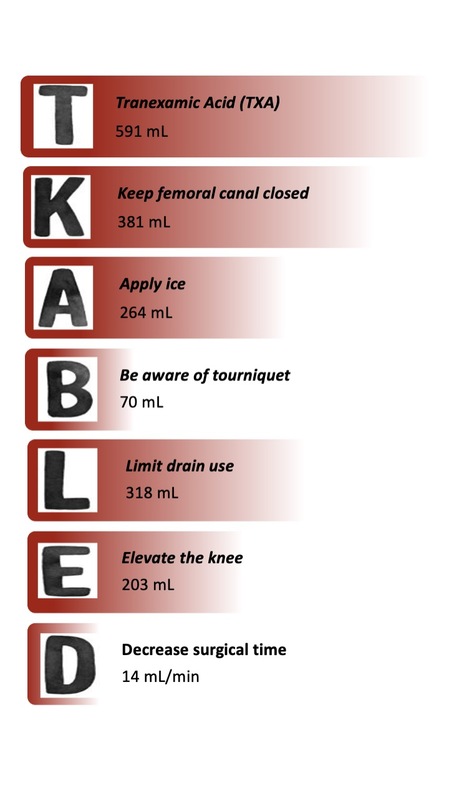

Based on gathered evidence, we suggest relying on the acronym TKA-BLED (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1

Strategies to enhance bleeding control in total knee arthroplasty (TKA-BLED). Values represent the potential total blood loss with the use of each strategy.

Tranexamic acid

Tranexamic acid (TXA) is a synthetic lysine analog that works by inhibiting fibrin breakdown through plasminogen [14]. Using TXA reduced total blood loss by a mean of 591 ml (95% CI: 536–647, p < 0.001). It also led to a significant reduction in the proportion of patients requiring blood transfusion (RR = 2.56, 95% CI: 2.1–3.1, p < 0.001) [15]. Administration of intravenous/topical/oral TXA, as well as combinations of them, is an effective strategy for reducing blood loss and the need for transfusion [16]. There is no clearly superior method or combination of methods – there is a slight difference suggesting that a combination of oral with intraarticular TXA may be more likely to prevent bleeding [17, 18]. Topical administration may be a reasonable alternative in patients with contraindications for systemic use of TXA [19, 20]. Tranexamic acid appears to be more effective when administered in a total dose greater than 3 g [17]. The administration of multiple doses of intravenous or oral TXA does not result in a significant reduction in calculated blood loss or the requirement for blood transfusion when compared to a single dose of intravenous or oral TXA [16]. A more recent meta-analysis showed that there was no statistically significant difference between intravenous TXA and topical TXA in terms of total blood loss (874.8 ±349.7 ml vs. 844.9 ±366.6 ml, respectively; SMD = 0.13; 95% CI: from –9.37 to 85.32; p = 0.15) or need for transfusion (10.9% vs. 15.4%, respectively; RR = 0.79; 95% CI: 0.60 to 1.04; p = 0.09), which supports the previous studies [21]. Tranexamic acid is more effective than other medications (aprotinin, ε-aminocaproic acid, fibrin) at reducing the need for allogeneic blood transfusion [19]. Importantly, recent reviews and clinical studies have consistently confirmed that TXA is a safe intervention in orthopedic procedures, including in patients with preexisting thromboembolic risk. A 2024 EFORT Open Reviews article reported no increase in thromboembolic complications, including death, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, myocardial infarction and stroke, associated with TXA use in TKA, while also reinforcing its efficacy [15, 22]. A study by Pecold et al. [21] showed no significant difference in particular types of adverse effects between intravenous and topical TXA groups.

Although the effectiveness of TXA in reducing blood loss is well established, the optimal dosing regimen remains uncertain. Current clinical guidelines, including those from the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, support the use of both low-dose (≤ 1 g or < 20 mg/kg) and high-dose (> 1 g or ≥ 20 mg/kg) intravenous TXA, with evidence showing that both regimens are effective. Multiple dosing strategies do not appear to confer a significant advantage over single-dose administration in terms of blood loss or transfusion rates. All administration routes – intravenous, topical, and oral – are considered equally effective, and the choice is often based on institutional protocol or individual patient risk profiles. This flexibility is valuable, particularly given that high total doses (> 3 g) may enhance efficacy, although further studies are needed to establish a standardized, evidence-based dosing protocol [15].

Keep the femoral canal closed

The meta-analysis by Wang et al. [23] demonstrated that patients with a sealed femoral canal experienced reduced total blood loss (MD = –381.29 ml, 95% CI: from –645.35 to –117.23 ml, p < 0.05), decreased transfusion rates (RR = 0.54, 95% CI: 0.43–0.68, p < 0.05), lower total drain output, diminished hidden blood loss, reduced drop of Hb level at day 1 postoperatively and less hematoma compared with the control group. Furthermore, there were no significant differences in rates of infection, deep vein thrombosis and redness of incision [23]. The most effective method of sealing the femoral canal is a combination of bone and cement [24].

Studies show that using extramedullary femoral alignment instead of the conventional intramedullary technique also reduces blood loss [25, 26].

Apply ice

Cryotherapy may reduce blood loss at one to 13 days after surgery – the mean difference was 264 ml (MD = 264 ml, 95% CI: 7–516 ml) when comparing the group receiving cryotherapy vs. the group without [27]. There is no demonstrated advantage of consistent cryotherapy using a device over intermittent cooling using ice bags regarding blood loss [28]. Cooling within the first 48 h after surgery is probably the most crucial, due to the peak of inflammation that occurs at this time [28].

Additionally, cryotherapy may also enhance the range of motion at discharge (MD = 8.3 degrees greater in group with cryotherapy vs. without; 95% CI: 3.6–13.1 degrees) [27], may slightly reduce pain at 48 hours on a 0 to 10-point Visual Analogue Scale (MD = 1.6 points lower; 95% CI: 2.3 lower to 1.0 lower) [27] and consequently decrease the need for opioid consumption during the first postoperative week [29].

Be aware of tourniquet

A randomized controlled trial (RCT) by Zhang et al. [30] found that the use of a tourniquet reduces intraoperative blood loss (207 ±56 ml in tourniquet group vs. 556 ±45 ml in control group) but does not affect significantly total blood loss – it may be explained by increased drain output and hidden blood loss. Total blood loss was higher in the tourniquet group by a mean of 70 ml (1,360 ±237 ml in tourniquet group vs. 1,290 ±279 ml in control group), but the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.16). Moreover, tourniquet application carries the possibility of various complications, including thigh pain, nerve palsy, ischemia, soft tissue damage, thromboembolic events, decreased muscle strength, and restricted range of motion [30]. A recent meta-analysis of RCTs by Magan et al. [31] reported even less favorable results for tourniquet: the tourniquet group had a longer hospital stay, a greater Hb drop (mean difference: 0.33; 95% CI: 0.12–0.54; p = 0.002), and higher transfusion rates (OR = 2.7; 95% CI: 1.4–5.3; p < 0.01) compared to the non-tourniquet group. Additionally, the pooled incidence of infection in the tourniquet group (4.0%, 95% CI: 2.7–5.4) was significantly higher in comparison to the non-tourniquet group (2.0%, 95% CI: 1.1–3.1) with an OR of 1.9 (95% CI: 1.1–3.76, p = 0.03) [31].

A recent study by Zhao et al. [32] investigated the effects of tourniquet use on total blood loss and early functional recovery in patients undergoing primary TKA with multiple doses of intravenous TXA. The study found that while the tourniquet group exhibited lower intraoperative blood loss (77.48 ml in the full tourniquet group vs. 137.04 ml in the limited tourniquet group and 212.99 ml in the no tourniquet group), it resulted in significantly higher total blood loss, including hidden blood loss, compared to the no tourniquet group (1,213.00 ml vs. 867.32 ml). Additionally, the full tourniquet group showed higher levels of muscle damage markers, including creatine kinase, C-reactive protein, and IL-6, suggesting increased muscle injury and inflammatory response. Early functional outcomes, such as pain, knee swelling, and quadriceps strength, were significantly better in the no tourniquet group compared to those in the tourniquet groups, with the no tourniquet group achieving superior scores on the American Knee Society Score (KSS) and range of motion assessments. These findings suggest that routine tourniquet use during TKA may not provide significant additional benefits over its absence, particularly when combined with TXA administration. Furthermore, tourniquet use may lead to increased total blood loss and muscle injury and risk of local complications, highlighting the potential advantages of alternative approaches, such as controlled hypotension, in improving postoperative outcomes [32].

The more efficient alternative is the use of controlled hypotension technique. With this technique there is increased intraoperative blood loss compared to the use of tourniquet, but controlled hypotension reduces Hb drop, postoperative drainage flow, and hidden and total blood loss after TKA. Additionally, the controlled hypotension technology helps to alleviate the postoperative hypercoagulable state, relieve inflammatory reactions, and facilitate early recovery of knee joint function after surgery [33].

Limit drain use

In the group of patients without drain release, total and hidden blood loss as well as the blood transfusion rate were significantly lower compared to the group with drain release: total blood loss: 535 ±295 ml vs. 853 ±331 ml, hidden blood loss: 513 ±290 ml vs. 689 ±324 ml (p < 0.05) [34]. This fact is explained by the loss of the tamponade effect [35]. A meta-analysis by Zhang et al. [35] showed that there was a significantly higher transfusion rate in the group with closed suction drainage compared to the group without drainage (RR = 1.50; 95% CI: 1.06–2.12; p = 0.02). An advantage of drain use was the lower rate of soft tissue ecchymosis (RR = 0.51; 95% CI: 0.28–0.91, p = 0.02) [35].

Additional evidence supporting the avoidance of routine drain use comes from a 2023 retrospective cohort study by Albasha et al. [36], which demonstrated several clinical advantages in patients who underwent TKA without drain placement. The no-drain group experienced a significantly shorter hospital stay (5.4 ±4.6 vs. 10.7 ±4.7 days, p = 0.000), shorter tourniquet time (80 vs. 111 minutes, p = 0.000), and less postoperative anemia, as indicated by smaller drops in Hb (1.2 ±0.7 vs. 1.8 ±1.0 g/dl, p = 0.000) and hematocrit levels (3.5 ±2.3% vs. 5.4 ±3.0%, p = 0.000). Patients without drains also required fewer transfused red blood cell units (0.04 ±0.2 vs. 0.18 ±0.6, p = 0.017) and received more postoperative anticoagulant doses (1.13 ±0.50 vs. 1.01 ±0.36, p = 0.025), possibly reflecting reduced bleeding risk [36]. These findings suggest that omitting closed-suction drains in primary TKA may contribute to improved recovery trajectories, reduced complication rates, and more efficient perioperative care, particularly when tranexamic acid is included in a multimodal blood management protocol.

Elevate the knee

Studies indicate that flexion of the knee reduces calculated blood loss, hidden blood loss, and the postoperative Hb drop compared to full extension of the knee, with a mean reduction of approximately 200–257 ml [37, 38]. This intervention is easy to implement and cost-effective.

However, there is no clear consensus on the exact limb position and duration of flexion. A study by Liu et al. [37] suggested elevation at the hip by 45o with 45o flexion at the knee on the grounds that previous studies have demonstrated that greater flexion does not further reduce blood loss, and may be uncomfortable for the patient due to increased immobility, increased wound stretch, and stimulation of pain receptors in flexion. Publications are also inconsistent regarding how long the knee should be flexed. Liu et al. [37] concluded that a 48–72 h postoperative knee flexion protocol should be implemented, citing studies that indicate the ineffectiveness of a procedure with a duration of less than 24 h. In contrast, Napier et al. [38] concluded that maintaining knee flexion for 6 h is also an effective method of reduction of blood loss. Shorter time of flexion (3 h) did not have this effect [38]. Additionally, the flexion of the knee immediately after TKA does not negatively affect the postoperative range of motion [37, 38]. When using this technique, caution is necessary due to possible nerve palsy. Patients should be carefully observed, and the position of the knee should be changed if they experience increasing discomfort – for this reason sciatic nerve block is not recommended when positioning the knee in flexion is planned [38].

A more recent randomized study from 2024 demonstrated that maintaining the knee in 60o of flexion, in combination with perioperative tranexamic acid administration, resulted in a significant reduction of total blood loss compared to extension (812.26 ±114.26 vs. 681.41 ±105.18 ml). This supports the effectiveness of early postoperative knee flexion as a blood-sparing technique, particularly when integrated with modern pharmacologic strategies [39].

Decrease operative time

A study by Ross et al. [40] demonstrated a significant relationship between surgical duration and calculated blood loss in patients undergoing total hip or knee arthroplasty, reporting an increase of 14.10 ml of blood loss per minute (p < 0.001). This equates to an estimated total blood loss of approximately 211.5 ml over a 15-minute interval. It also showed that prolonged operative time increases risk of allogeneic blood transfusion (OR = 1.35 per 15 min, p < 0.001). Notably, after 80 min of surgery, the risk of blood transfusion grows faster [41]. Furthermore, prolonged surgery time contributes to higher risks of readmission, reoperation, surgical site infection and wound dehiscence [41].

Other considerations

Modified Robert Jones bandage

A meta-analysis conducted by Li et al. [33] revealed no significant advantage of the modified Robert Jones bandage (MRJB) over conventional dressing concerning total blood loss (MD –25.41; 95% CI: from –90.52 to 39.70; p = 0.44), intraoperative blood loss, drain blood loss and transfusion rate (RR = 0.95; 95% CI 0.55–1.64; p = 0.86). Additionally, MRJB application may be associated with potential complications such as peroneal paralysis, pressure ulcers, bruise, and blisters [42]. Current evidence does not fully support or neglect use of MRJB after TKA.

Electrocoagulation

One of the methods of ensuring hemostasis intraoperatively is electrocoagulation. Nowadays, there are available various technologies such as traditional electrocautery (TE), saline-coupled bipolar sealer, and argon beam coagulation [43]. A meta-analysis by Chen et al. [44] reported that the use of a bipolar sealer during TKA presented only a small reduction in terms of total blood loss (WMD = –123.80, 95% CI: from –236.56 to – 11.04, p = 0.031) when compared to standard electrocautery. No significant differences were observed in the need for transfusion, blood loss in drainage, Hb levels at discharge, Hb drop, or length of hospital stay (p > 0.05) [44]. A study by Krauss et al. [45] presented convergent results showing that the safety, efficacy, and outcome profile of the unipolar electrocautery system compared to the bipolar sealing system were similar. The study by Rosenthal et al. [43] also included argon coagulation in the comparison, indicating that these 3 hemostasis systems were statistically equivalent with respect to estimated blood loss. The mentioned studies also note increased costs of the procedure when a device other than TE is used [43, 45]. Thus, existing evidence does not endorse routine use of a bipolar sealer or argon beam coagulation during TKA.

Cell salvage

Cell salvage is a procedure in which contents of drainage are collected, filtered, and re-administered in the postoperative period. Existing studies indicate that cell salvage is less effective than intra-articular TXA for reducing blood loss, variation of hematocrit, need for blood transfusion, and in-hospital stay [14, 17].

Platelet-rich plasma

The effect of platelet-rich plasma (PRP) use is not superior to TXA, but it needs further investigation. The PRP group exhibited a higher mean total drain output (698 ml vs. 469 ml), with this difference reaching statistical significance. Also, there were significant differences in Hb level reduction (PRP: 2.08 vs. TXA: 1.21), although the transfusion rates remained equal between groups [46].

Correction of preoperative anemia

Preoperative anemia is the main predictive factor for the necessity of blood transfusions in TKA. The Enhanced Recovery in Orthopedic Surgery consensus recommends that patients before TKA should undergo screening for anemia. If Hb levels before surgery are found to be less than 13 g/dl, regardless of gender, optimization of Hb levels is advised [47]. Methods that may be considered [47]:

Iron therapy: Iron deficiency is the predominant cause of preoperative anemia, with treatment modalities encompassing oral or intravenous supplementation. Oral iron therapy, typically administered at a daily dose of 150 mg of ferrous salt, is cost-effective and convenient; however, its efficacy is limited due to low absorption rates. The average treatment duration prior to TKA was prolonged, with a mean of 134.5 days. Intravenous iron supplementation (doses 600–1,000 mg) is more effective and faster and may be considered in some clinical conditions such as malabsorption, chronic inflammation, or situations where surgery cannot be postponed. The therapeutic effect peaks approximately 2 weeks after administration [47]. Recent data from a Jorgensen et al. study [48] in hip and knee arthroplasty support the importance of identifying and addressing iron deficiency anemia (IDA). In a prospective analysis of 3,655 patients, those with IDA (defined as Hb < 13 g/dl and transferrin saturation < 20%) were more likely to experience a postoperative length of stay exceeding two days, and higher 30- and 90-day readmission rates compared to non-anemic patients. Although many adverse outcomes were attributed to comorbidities and frailty, the findings underscore that IDA is a modifiable risk factor worth addressing preoperatively [48].

Recombinant human erythropoietin (rHuEPO): It is used for managing mild preoperative anemia (Hb 10–13 g/dl). The recommended protocol consists of 4 injections of 600 IU/kg rHuEPO or 21 days before surgery combined with 4 weeks long oral supplementation of 150 mg of ferrous salts. The therapy should be interrupted if the Hb level reaches 15 g/dl [47].

Rheumatic diseases

Patients with rheumatic diseases, particularly rheumatoid arthritis (RA), undergoing TKA face distinctive challenges related to perioperative blood loss and transfusion requirements. These challenges arise due to a combination of chronic inflammation, altered hemostasis, and the pharmacological effects of antirheumatic medications. Several studies highlight the multifactorial nature of these risks and underscore the need for targeted perioperative strategies. Studies show that RA patients have increased risk of blood transfusion and prolonged hospital stay when compared to OA patients [49].

This group of patients is more likely to have anemia of chronic diseases or iron deficiency anemia, the diagnosis and treatment of which is particularly important, as it is a strong risk factor for the need of allogeneic blood transfusion [49, 50].

Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), frequently prescribed for RA management, have been associated with increased perioperative blood loss when compared to OA patients. In a retrospective study by Jiang et al. [51], RA patients treated with DMARDs demonstrated significantly greater total blood loss (804 ml vs. 654 ml, p = 0.001) and intraoperative blood loss (113 ml vs. 75 ml, p = 0.002) than OA patients. However, no statistically significant differences were noted in transfusion rates or perioperative complications between RA patients who received DMARDs and those who did not [51].

In addition, it is worth noting that RA patients have a higher risk of infection than the general population, so it seems especially important to reduce the allogeneic transfusions rate among this group [52].

Discussion

Total knee arthroplasty is vital for end-stage OA treatment but often leads to significant blood loss, increasing morbidity and healthcare costs. This review emphasizes the TKA-BLED acronym as a comprehensive strategy for effective blood management. Key components, including TXA, sealing the femoral canal, and cryotherapy, have been shown to significantly reduce total blood loss and the need for allogenic blood transfusions. Additionally, managing surgical time and proper knee positioning are efficient in minimizing blood loss. Addressing preoperative anemia with iron therapy and rHuEPO further enhances patient outcomes. Implementing these strategies can help achieve a “zero” allogenic transfusion rate, ultimately improving recovery and safety for TKA patients.

However, accurate assessment of blood loss in clinical studies remains challenging. Multiple studies have demonstrated that different estimation methods – such as Hb-based formulas, suction measurement, and gauze weighing – lack standardization and vary widely in accuracy [53]. These inconsistencies may partially explain the heterogeneity of results observed across clinical trials and meta-analyses. Moreover, the observed reductions in blood loss associated with TKA-BLED components must be interpreted considering these limitations. Future studies should adopt consistent, validated methods of quantifying blood loss to ensure more reliable data comparisons.

Recent literature highlights the importance of adopting individualized, multimodal blood conservation strategies rather than relying on single interventions. As emphasized by White et al. [54], perioperative blood management in TKA should be integrated into standardized care pathways, combining pharmacologic agents such as tranexamic acid with procedural elements such as tourniquet optimization and preoperative anemia correction. Importantly, they stress that outcomes are optimized when multiple techniques are combined and tailored to the patient’s individual risk profile.

Pempe et al. [55] further support this approach by identifying key predictors of blood loss and transfusion – such as preoperative Hb level, body mass index, operative time, and drain output. Their analysis underscores the need to account for these modifiable risk factors when designing perioperative strategies aimed at minimizing transfusion requirements.

Liu [56] also advocates for comprehensive blood conservation protocols in joint arthroplasty, emphasizing that integrating pharmacological agents, intraoperative techniques, and preoperative patient optimization yields superior outcomes compared to isolated interventions.

Together, these findings emphasize that effective blood management in TKA requires a bundled and patient-centered approach. This strengthens the justification for the TKA-BLED framework as a clinically valuable, adaptable tool for guiding evidence-based perioperative care.

Study limitations

This study has several limitations. Primarily, it is a narrative review, underscoring the need for a systematic review with meta-analysis to strengthen the evidence base. Additionally, many studies included in this review were conducted on small patient groups with limited follow-up periods, and some present inconclusive or conflicting results.

Further randomized controlled trials are needed, involving larger patient populations and extended follow-up periods, to evaluate the efficacy and potential complications of these methods. It is especially important to assess the real-world performance of bundled strategies such as TKA-BLED under consistent monitoring conditions. Studies assessing the combined effects of multiple strategies are also essential. Finally, a systematic review with meta-analysis is required to establish a practical protocol for managing blood loss and transfusion requirements in patients undergoing TKA.

Conclusions

The TKA-BLED approach provides an effective strategy for blood management in TKA, significantly reducing blood loss and minimizing transfusion needs. This method enhances patient outcomes, lowers complication risks, and supports improved recovery in TKA patients. Patients with rheumatic diseases represent a special group who require a multidisciplinary approach, as they are at increased risk of blood loss and the need for allogeneic transfusion.