Kawasaki disease (KD), previously known as mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome, is a medium-size vessel disease affecting mostly children. While the pathophysiology of the disease is still not fully understood, it is hypothesized to have a genetic or even infective cause [1]. In this study, we provide an updated epidemiological background of the disease in the United States.

An analysis was conducted using the 2016 Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project Kid’s Inpatient Database (HCUP KID). It is compiled by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and involves multiple partners [2, 3].

The sample consisted of patients below the age of 21. The International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) code for “Mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome” (M 30.3) was used to identify patients with a diagnosis of Kawasaki disease [4]. The data were converted to weighted form and differences in gender, month of year, race, region, and household income were studied using Pearson’s χ2. We further used linear regression to investigate the total charges [5].

There were 5503 weighted cases of Kawasaki disease in the 2016 KID database (Table I). Kawasaki disease was more common in males (3345, 60.8%) than females (2158, 39.2%) (p < 0.01). Statistically significant racial differences were also identified (p < 0.01) as more patients were white (1913, 38.1%). However, a higher prevalence among patients of Asian or Pacific Islander background (0.2%) was observed compared to the remaining ethnic groups (white: 0.1%, black 0.1%, Hispanic 0.1%). The southern regions of the United States reported the highest rate of admission with 2036 patients (37%) diagnosed and treated for the condition.

Table I

Characteristic findings of Kawasaki patients between the ages of 0–20

We also found that the disease was more common in families with a median household income exceeding $71,000 (26.7%), closely followed by those earning between $54,000 and $70,999 (26.6%) (p < 0.01). The median age on admission was 2 years (interquartile range [IQR] of 1–5, p < 0.01) and the median charge was $32,170 (IQR: $20,825.00–$50,502.05) (p < 0.01). While the median length of stay of children with KD was 3 days (IQR: 2–5 days), linear regression showed that it lacked statistical significance (B = 0.007, p = 0.953, 95% CI = 0.236–0.251).

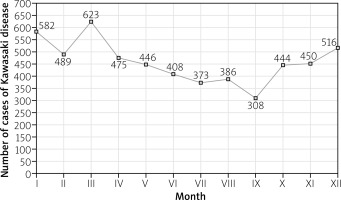

Seasonal differences were also studied and the findings are illustrated in Figure 1. Most admissions of Kawasaki disease were recorded in winter. A seasonal increase started in October and peaked in March (623, 11.3%) (p < 0.01), despite a transient drop in February. The incidence started tapering in April and the nadir was in September.

Fig. 1

Admissions for Kawasaki disease in patients between ages of 0–20 in the United States between 1st January 2016 to 31st December 2016.

Since there are multiple cardiovascular complications associated with KD, prompt hospitalization and proper management of the condition are vital. The higher male to female ratio (1.55 : 1) and increased prevalence among “Asians or Pacific Islanders” seen in our study are compliant with multiple previously published studies. Similar peaks in winter have also been reported in Japan [6]. We also observed a monomodal distribution of the age groups with a peak at 2 years and 78.9% of all cases were below the age of five.

There are some limitations to our study. The HCUP database does not classify Asians separately for a comparison to be made for that specific ethnic group only. We also did not have any history from the parents or siblings and therefore were unable to test the infectious and genetic theories.