Introduction

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) is a chronic disease characterized by joint inflammation in children under the age of 16, persisting for more than 6 weeks. Genetic factors, infections, and environmental factors are believed to contribute to the development of an abnormal immune system response. As a result of persistent chronic inflammation, joints become damaged. The synovial membrane thickens and transforms into a kind of scar tissue that grows in the joint, covering the articular cartilage. The articular cartilage and the bone ends forming the joint are destroyed, and pseudocysts are formed. The consequences of ongoing inflammation include swelling and tension in the periarticular tissues and muscles, as well as accompanying pain [1, 2]. Most often, large peripheral joints are involved. Pain and swelling cause reduced mobility, which leads to decreased physical activity (PA). Lack of movement in children with JIA can lead to cardiovascular disease, joint contractures, muscle weakness and poor postural control. In children with JIA, physical examination sometimes reveals abnormal growth of the lower limb bones near the affected joint with its characteristic valgus position. Abnormal posture affects the mechanics of adjacent joints, disrupts or alters movement patterns, and can intensify bad habits, eventually leading to disability [2–4].

In November 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) published new PA guidelines for children and adolescents, recommending an average of 60 minutes a day of moderate to vigorous intensity aerobic activity at least 3 days per week [5]. An adequate level of PA is essential for a child’s proper development. Physical activity influences normal growth, prevents many diseases, and has psychological and social benefits. Insufficient PA in children leads to many diseases, metabolic disorders and hypertension in later life. Numerous studies have shown that without an adequate amount of exercise, the human body develops less efficiently and at a slower rate [6]. Therefore, according to the WHO, any movement is better than no movement. Children with JIA belong to the group of children with a chronic disease affecting the musculoskeletal system. Current research for JIA, in addition to pharmacological treatment, recommends the use of rehabilitation and regular PA that takes into account the child’s current health and functional status. Movement improves the physical and mental state in children. Participation in sports activities positively impacts overall health, provides biological benefits, minimizes the effects of the disease, reduces the possibility of cartilage damage and optimizes bone mineral density [4, 7, 8]. Exercise can delay structural changes and help establish proper compensatory movement patterns that enable independence and self-reliance in children with JIA [3, 9, 10].

The aim of the study was to confirm that children with JIA are more often exempt from physical education (PE) classes at school, as well as to examine their PA during leisure time and how they spend their time compared to healthy peers.

Material and methods

Patients and study design

The study group was recruited from patients admitted to the Department of Rehabilitation or Clinic and Polyclinic of Rheumatology of the Developmental Age, National Institute of Geriatrics, Rheumatology and Rehabilitation (NIGRiR) in Warsaw. Researchers prescreened the patients upon admission and generated a list of potential study participants. The inclusion criteria were as follows: age 7–13 years, diagnosis of JIA (all subtypes of JIA were eligible), disease remission, and a need for physiotherapy consultation or intervention. The exclusion criteria included high disease activity or refusal to participate. Both patients and their legal guardians were approached for consent. The control group was recruited among healthy children from elementary schools in Pruszkow and Nysa. Written informed consent was obtained from the legal guardians of all participants in both groups. An anonymous, original on-paper questionnaire was used to collect data. The questionnaire was modeled after the Health Behavior in School-aged Children (HBSC) [11, 12] survey and reviewed available tools for assessing children’s PA [13]. In designing the survey, the PAs most frequently cited in scientific publications and those preferred by children in Poland were considered [14, 15]. Additionally, participants had the opportunity to list any other activities they engaged in. The survey contained general questions and questions about the child’s health, frequency of participation in typical forms of activity, such as running, biking, scootering, roller skating and rollerblading, skipping, time spent outdoors, attendance at PE classes, and time spent in front of the TV and computer. The survey assessed children’s PA over the previous 6 months. No explanatory sessions were provided.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed at the Department of Gerontology, Public Health, and Didactics at National Institute of Geriatrics, Rheumatology and Rehabilitation. Data were processed using the Statistica 13.5 program. The χ2 test was applied to examine differences between the study groups, and a p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Bioethical standards

This study was conducted between September 2018 and January 2019, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by the Bioethics Committee of the National Institute of Geriatrics, Rheumatology and Rehabilitation (approval number: KBT-7/1/2018, date of approval: 04.10.2018). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants and their legal guardians.

Results

Groups’ main features

A total of 49 subjects were included in the study: 29 children with JIA in the study group (median age 11 years, range 9–12), consisting of 19 girls (66%) and 10 boys (34%), and 20 healthy volunteers in the control group (median age 9.5 years, range 7.5–12), consisting of 11 girls (55%) and 9 boys (45%). The two groups were similar in terms of age, gender, and place of residence (Table I).

In-school and out-of-school physical activity

A significant proportion of children with JIA, compared to their healthy peers, did not attend PE classes. In the JIA group (group A), 17 of children (59%) attended PE, compared to 20 (100%) in the control group (p = 0.003) (Table II). There were no significant differences in the frequency of extracurricular activities between children with JIA and healthy children in most of the activities examined (Table III). For nine out of the 13 activities considered, the frequency of participation was the same for both sick and healthy children (p-values ranged from 0.218 to 0.851). For 3 activities, the difference in frequency of participation between healthy children and children with JIA was on the verge of significance: running – sport (p = 0.079), dance – sport (p = 0.074), and scooter riding (p = 0.083). The only extracurricular activity that was more frequently performed by healthy children than children with JIA was martial arts (p = 0.033).

Table II

Participation in PE lessons

| Study group (n = 29) | Control group (n = 20) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attends a physical education lesson [n (%)] | 17 (59) | 20 (100) | 0.003 |

| Does not attend physical education lessons [n (%)] | 12 (41) | 0 (0) |

Table III

Out-of-school activities

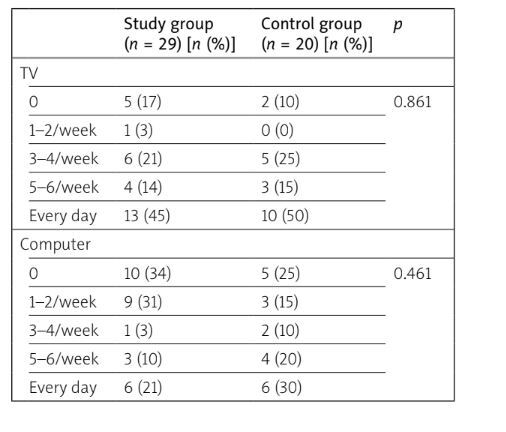

Screen time

There were no significant differences in the frequency of time spent watching TV (p = 0.86) or using the computer (p = 0.46) between group A and group B (Table IV).

Discussion

Chronic illness often results in reduced PA, which negatively affects psychomotor and psychosocial development in children [6]. On one hand, a child’s motor activity decreases due to bodily weakening, fatigue, and various disease-related symptoms; on the other hand, the treatment process often requires children to avoid intense PA and spend more time in bed [16]. Children who engage in PA during their free time tend to have a better sense of well-being. It is important for children with JIA to lead as normal a lifestyle as possible. They should spend time with peers and not feel different from them. It is also crucial for them to maintain independence and cope with the limitations imposed by the disease. However, if certain forms of PA are not recommended by doctors, they should be replaced with others, rather than removing PA entirely. For example, children with JIA can engage in activities such as swimming, cycling, or gymnastics.

The study aimed to assess the impact of JIA on the extracurricular activities of school children. It was found that children with JIA and healthy children showed similar levels of participation in extracurricular activities in the parameters we examined. No significant differences were found in either PAs (e.g., running, cycling, games) or other forms of leisure activities (e.g., TV, computer use). This suggests that the disease process associated with JIA does not significantly influence the preference for a sedentary lifestyle at the expense of PA, which could have been expected due to changes in the musculoskeletal system. In contrast, a study by Bos et al. [17] found that children with JIA exhibited lower levels of PA compared to healthy children. They assessed functional levels using the CHAQ-38 (Child Health Assessment Questionnaire) and daily PA using the Bouchard diary. The results showed that children with JIA had significantly lower levels of PA (p = 0.01), spent significantly more time in sedentary activities (p = 0.02), and engaged less in intense and moderate exercise (p = 0.06) [17]. These findings contrast with the present study, which did not observe significant differences between children with JIA and healthy children regarding the choice of daily activities. However, it remains unclear whether the activities were pursued with the same intensity. For instance, cycling can vary in intensity, depending on how and under what conditions it is performed.

The purpose of our study was not to assess the physical fitness of children with JIA compared to healthy peers, but rather to evaluate whether the disease influences the choice of PAs. It is likely that, in fitness tests, children with JIA would perform worse than their healthy peers, as supported by other studies. For example, Patti et al. [18] reported that children with JIA had lower levels of physical fitness than healthy children. They found that children with JIA scored significantly lower in 3 tests: the Abalakov test (control group 38.67 ±17.48 cm vs. JIA 29.06 ±12.74 cm; p < 0.05), the right-hand grip test (control group 23.08 ±11.37 kg vs. JIA 16.65 ±7.82 kg; p < 0.05), and the left-hand grip test (control group 22.15 ±10.08 kg vs. JIA 15.64 ±6.318 kg; p < 0.05). Additionally, posturography tests revealed significant differences in sway path length (control group 543.2 ±300.2 mm vs. JIA 921.2 ±430.7 mm; p < 0.001) and ellipse area (control group 84.47 ±47.94 mm² vs. JIA 165.8 ±215.7 mm²; p < 0.05). The lower level of physical fitness in children with JIA is not surprising, given that the disease affects the musculoskeletal system, which in turn impacts motor skills. However, it is noteworthy that children with JIA can still perform and enjoy the same PAs as their healthy peers, as demonstrated by our study’s findings on extracurricular activities, where no significant differences were observed between children with JIA and healthy children in terms of leisure activities.

It is, however, surprising that a large proportion of children with JIA did not participate in PE lessons (41%), while all healthy children attended PE. This might be due to the underutilization of the option allowing students to be exempt from specific exercises rather than complete exemption from PE lessons, which was introduced in Poland in 2015 [19]. The intent of this change was to enable students with specific exercise limitations to still participate in PE classes. Based on our own experience working with children with JIA, a significant proportion of these children do not require total exemption from PE. The discrepancy between participation in extracurricular activities (especially PAs) and participation in PE lessons raises questions about the legitimacy of some total exemptions. A study by Milatz et al. [8] highlighted this issue, noting that the attendance of children with JIA in sports activities increased from 31% in 2000 to 64% in 2015, while the number of children exempted from sports activities decreased from 44% in 2000 to 16% in 2015. They observed the beneficial effects of biological treatment on these rates but also noted that some patients continued to avoid PA. We agree with this view and, based on our research and experience, we believe it is important to implement measures to increase participation of children with JIA in PE classes.

Conclusions

The results of the study showed that children with JIA aged 7–13 years engage in the same types of extra-curricular activities as their healthy peers, with the exception of martial arts, which they participate in less frequently. Furthermore, children with JIA are more often completely exempted from PE classes, raising concerns about the validity of these exemptions, especially since no significant differences were found in the choice of PAs between healthy children and those with JIA. A key conclusion is the need for further investigation into the issue of PE exemptions and the implementation of measures to increase the participation of children with JIA in PE classes, particularly with regard to available adaptations based on their health condition.