Introduction

Definitions and epidemiology

The lumbosacral segment of the spine performs several diverse roles. It supports the upper segments (support function) by transmitting forces and bending moments to the pelvis via both sacroiliac joints. The lumbosacral segment of the spine protects the spinal cord and nerve roots from damage by providing a protective sheath. In addition, it performs a cushioning function via the lumbar curvature and intervertebral discs, allowing simultaneous motor functions: flexion, extension, lateral bending, and rotation [1]. Fulfilling such an important role, any anatomical deviations of the lumbosacral junction can affect a patient’s functionality and lead to pain symptoms. Bony anomalies of the lumbosacral transition include sacral lumbarizations and sacralizations of the lumbar vertebrae. Both anomalies refer to the so-called lumbosacral transitional vertebrae (LSTV). The LSTV is described in the literature as a complete or partial unilateral or bilateral anastomosis of the transverse process (TP) of the lowest lumbar vertebra with the sacrum [2, 3]. The association of the occurrence of LSTV with low back pain (LBP) was first described in 1917 by Mario Bertolotti [4]; hence the pain syndrome associated with this anomaly is referred to as Bertolotti’s syndrome.

Based on the available literature, the prevalence of LSTV in the LBP population ranges from 4 to 35%, mainly affecting individuals under 40 years of age (50.6%). In women and men, LSTVs occur with similar frequency [5]. The most common form of LSTV is the type with unilateral pseudoarticulation between the TP and the sacral ala [5, 6]. The presence of LBP and/or lumbar radiculopathy was observed in 96.4% of patients with this abnormality [2, 3, 5–7]. The most common LBPs are found in patients with unilateral pseudoarticulation between the TP and the sacral ala and in patients with co-existence of pseudoarticulation on one side and fusion on the opposite side between the TP and the sacral ala [3].

Classifications lumbosacral transitional vertebrae

Various classifications of LSTV have been presented in the literature. Most classifications are based on the morphological characteristics of the lumbosacral transition area. A unique classification is the Onyiuke Grading Scale, which takes into account the location of the anomalies, their extent, the coexistence of other defects, and the nature of the LBP. Table I presents a summary of transitional vertebral classifications based on the existing literature [8–12].

Table I

| Castellvi classifications (1984) [8] | O’Driscoll transitional lumbosacral junction morphology (1996) [9] | Mahato classifications (2013) [10] | Onyiuke Grading Scale (2021) [11] | Jenkins classifications (2023) [12] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Based on the morphologic characteristics | Based on the morphology between what was considered to represent the uppermost sacral segment (s1) and the remainder of the sacrum | Integrating the full spectrum of morphological alterations in a biomechanical continuum | Based on location, severity, and characteristics of pain experienced due to LSTVs | Based on the concept of a reduced gap between the TP and SA |

| Grade I | Type I | Type I: dysplastic L5 TP | Grade I | Type 1 |

| Grade I a Enlarged L5 TP unilaterally Grade I b Enlarged L5 TP bilaterally | No disc material With without transitional segments | Type I A Unilateral TP ≤ 19 mm in width Type I B Bilateral TPs ≤ 19 mm in width Type I A F(i/c) or Type I B F(i/c) With presence of ipsi-/contralateral rudimentary facet to the side of the L5 enlargement Type I A F2 or Type I B F2 With presence of bilateral rudimentary facets | Grade I a No clinical symptoms and radiographic LSTV of single level Grade II a No clinical symptoms and radiographic LSTV of multiple level | Type 1A Unilateral dysplastic TP (< 10 mm between TP and SA) Type 1B Bilateral dysplastic TP (both sides < 10 mm gap) |

| Grade II | Type 2 | Type II: accessory articulations | Grade II | Type 2 |

| Grade II a Incomplete S or incomplete L, enlarged TP and PA between TP and the SA unilaterally Grade II b Incomplete S or incomplete L, enlarged TP and PA between TP and the SA bilaterally | Small residual disc (anteroposterior length less than that of the sacrum) Mostly without transitional segments | Type II A Unilateral L5-S1 accessory articulation Type II B Bilateral L5-S1 accessory articulations Type II A F (i/c) or Type II B F(i/c) With presence of ipsi-/contralateral rudimentary facet to the side of the diarthrosis Type II A F2 or Type II B F2 With presence of bilateral rudimentary facets | Grade II a Isolated LBP and radiographic LSTV of single level Grade II b Isolated LBP and radiographic LSTV of multiple level | Type 2B Incomplete unilateral L/S with enlarged TP that has a joint between itself and SA (< 2 mm separation, but > 10 mm gap on the opposite side) Type 2B Incomplete bilateral L/S with enlarged TP that has a pseudo-joint between itself and SA (< 2 mm of separation on both sides) Type 2C Dysplastic TP on one side and incomplete L/S on the other side (< 10 mm but > 2 mm on one side and < 2 mm on the other side) |

| Grade III | Type 3 | Type III: sacralizations | Grade III | Type 3 |

| Grade III a Complete L or S, the enlarged TP with complete fusion with the SA Ia: unilaterally Grade III b Complete L or S, the enlarged TP with complete fusion with the SA bilaterally | Well-formed disc extending the entire anteroposterior length of the sacrum With LSTV or with normal spinal | Type III A Unilateral L5–S1 sacralization Type III B Unilateral complete S with contralateral L5–S1 PA Type III C Bilateral complete L5–S1 sacralization Type III A F (i/c) or Type III B F(i/c) or Type IIIC F With presence of ipsi-/contralateral rudimentary facet to the side of the S Type III A F2 or Type III B F2 or Type III C F2 With presence of bilateral rudimentary facets | Grade III a LBP with radiculopathy and radiographic LSTV of single level Grade III a LBP with radiculopathy and radiographic LSTV of multiple level | Bilateral L/S with complete osseous fusion of the TP to the SA |

| Grade IV | Type 4 | Type IV: lumbarizations | Grade IV | Type 4 |

| Unilateral Type IIa on one side with Type IIIa on the contralateral side of the same LSTV | Well-formed disc extending the entire anteroposterior length of the sacrum With the addition of squaring of the presumed upper sacral segment | Type IV A Incomplete/partial lumbarization of S1 as an accessory S1–2 articulation Type IV B Unilateral complete separation of S1 from sacral mass Type IV C Bilateral S1–2 accessory articulation Type IV D Complete S with residual four segment sacrum Type IV A F(i/c) or Type IV B F(i/c) or Type IV C F or Type IV D F With presence of ipsi-/contralateral rudimentary facet to the side of the diarthrosis Type IV A F2 or Type IV B F2 or Type IV C F2 or Type IV D F2 With presence of bilateral rudimentary facets | Grade IV a LBP with radiculopathy, other spinal pathology, and radiographic LSTV of single level Grade IV b LBP with radiculopathy, other spinal pathology, and radiographic LSTV of multiple level | Type 4A L/S with complete osseous fusion on one side dysplastic TP on the other side (type 1 on one side, type 3 on the other side) Type 4B L/S with complete osseous fusion on one side and incomplete L/S on the other side (type 3 on one side, type 2 on other side) Type 4C L/S with complete osseous fusion on one side, > 10 mm gap on other side (type 3 on one side, type 1 on other side) |

Radiological diagnosis

The most common methods of diagnosis are X-ray and higher resolution imaging: magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography (CT). Bone scintigraphy is also helpful. The literature reports a new method of radiography (the EOS imaging system) that may have significant implications for understanding LSTV [2, 3]. The EOS system can add significant value to the diagnosis and management of patients with LSTV, allowing for 3D reconstruction without CT and eliminating the need for MRI, reducing cost, saving time, and minimizing error in correctly numbering spinal levels [2].

Anatomical differences in lumbosacral transitional vertebrae

Bone and joint structures

The variability of LSTV (different anatomical variants on radiographs) has clinical and therapeutic implications. Thus, patients with LSTV present unilaterally or bilaterally: wide TP, pseudoarticulations and complete fusion of TP with sacrum ala. However, other anatomical variations in LSTV patients have also been described in the literature. It was observed that L5–S1 pseudoarticulations were associated with increased lordotic curvatures, irregularities of L5 vertebral heights, and pedicle and angular dimensions [13]. Increased lumbar lordosis may predispose these individuals to more rapid progression of facet degeneration and degenerative spondylolisthesis [14]. On the other hand, decreased lumbar lordotic curvature is strongly associated with LBP [15].

In addition, Mahato associated the presence of L5–S1 fusion with smaller disc heights, wider and shorter L5 pedicles, narrower and taller TPs, and straighter spines (smaller lordotic angles) [16].

The first lumbar vertebra and the number of lumbar vertebrae are determined by the presence and classification of the transitional ribs at T12 or L1. Patients with LSTV may present with sacralization or lumbarization. Mahato observed variations in bone structures in people with LSTV with different numbers of lumbar vertebrae. He observed the occurrence of decreased S1 pedicle height and sagittal pedicle angulation with increased downward slope in patients with sacralization, while lumbarization was associated with more open peduncles in the sagittal plane and a shorter length between the facet and sacral promontory dimensions [14].

Muscles

Becker et al. [17] noted a different load on specific muscles in patients with LSTV compared to individuals without these abnormalities. In the CT images analyzed, they observed muscle atrophy of the psoas muscle (p = 0.028), paraspinal muscles (p < 0.001), rectus abdominis muscle (p < 0.001), and obliquus abdominis muscle (p < 0.001), and more fatty muscle changes for all analyzed muscles in patients with LSTV [17]. Reduced muscle volumes have also been observed by other investigators [18]. In addition, Becker et al. [17] noted significantly greater total muscle degeneration of all analyzed muscles in LSTV patients compared to the control patient group (without LSTV).

Ligaments

In addition, it is necessary to emphasize the importance of the iliolumbar ligament, which has an important role in the biomechanics of the lumbosacral spine. This ligament has certain functions in the stabilization of the spine, and this action is more prominent in lateral flexion than during movements in the sagittal plane [19]. However, the iliolumbar ligament is the weakest ligamentous stabilizer of its area, and it is susceptible to injury due to its angulated attachment. This ligament is attached to the ilium at an angle of approximately 45° [19, 20]. In addition, through its rich innervation (large presence of type IV nerve endings), it plays a role in the proprioception of the lumbosacral region. All this may promote the development of pain in this area [21].

A postmortem study by Aihara et al. [22] proved that at the level immediately above the transitional vertebrae, the iliolumbar ligament is thinner and weaker compared to those without LSTV. This, in turn, can destabilize the lumbosacral region and contribute to the earlier development of degenerative changes. On the other hand, the formation of a joint or bony connection between the lumbar vertebra and sacrum in the LSTV may be an adaptive mechanism to compensate for the weak iliolumbar ligament and preserve spinal stability [3, 22].

Biomechanics

The presence of LSTV is associated with variation in movement and with stresses on the patient’s spine. The LSTV may be a cause of hypomobility at the L5–S1 level and hypermobility at the suprajacent and superior lumbar levels [23]. Unilateral LSTV results in asymmetric biomechanical changes. The larger proportion of load is borne by the side with an additional L5–S1 relationship, which results in lateral tipping of the iliac crest and convexity of a scoliotic curve towards the LSTV side. On the side with pseudoarticulation, the sacroiliac joint is overstressed, more worn and irritated. The muscles on the LSTV side are also more active. All these changes can be potential causes of secondary problems, such as early degenerative changes [24, 25].

Treatment in lumbosacral transitional vertebrae with low back pain

The number of published studies relating to the topic of LSTV and treatment management has increased in recent years [5]. Treatment management options for LSTV cover [5]:

conservative treatment: pharmacology (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, glucocorticosteroids [GCs]), physiotherapy (manual therapy, mobility training, motor control training, myofascial techniques);

minimal invasive interventional therapies: GCs injections, radiofrequency ablations;

surgery treatment: resection of the pseudoarticulation, decompression of the bone osteophyte, spine fusion, and other endoscopic techniques.

Physiotherapy is one of the most widely used forms of treatment in LBP. Physiotherapy or physiotherapy combined with educational programs can reduce pain and improve the function and quality of life for patients and also reduce the risk of a future LBP episode, as well as the future severity of LBP [17]. Such benefits can be achieved through various techniques of physiotherapy tailored to individual needs in patients treated both conservatively and surgically.

The literature also underlines the importance of physiotherapy in the treatment of LSTV patients in non-surgical and surgical management. Published reviews on the treatment of LSTV present limited data on physiotherapeutic treatment options. These are based only on a few published articles considering physiotherapeutic management alone, making it difficult to analyze the effectiveness of the therapy used [2, 3, 7].

The purpose of this review is to comprehensively present the issue of conservative treatment incorporating modalities of physiotherapy based on the available publications in the literature.

Material and methods

Search strategy

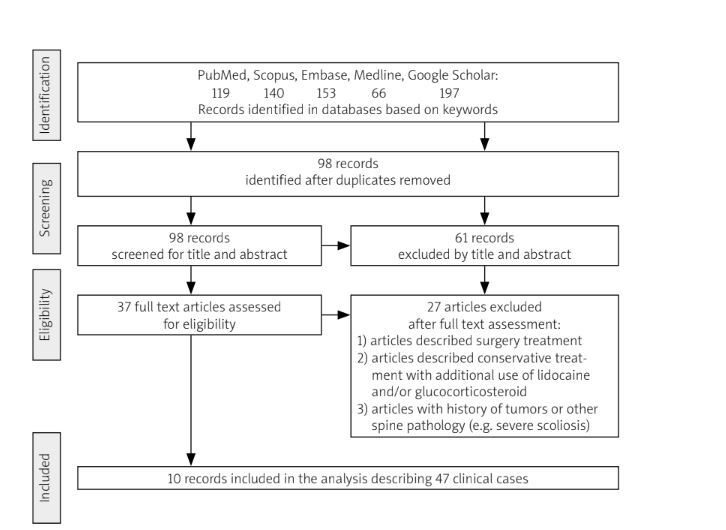

The PRISMA statement [26] used for review is included in the supplementary materials. Two authors independently conducted a search using the databases PubMed, Scopus, Embase, Medline, and Google Scholar from November 20 to December 31, 2023. The articles published up to the end of December 2023 were reviewed. The keywords used in the literature search contained words and phrases related to LSTV, Bertolotti’s syndrome, physiotherapy, conservative treatment, exercises, mobilizations, manual therapy, chiropractic management. The full description of the search strategy is available in the supplementary material. Reference lists from the found documents helped to identify additional articles and other types of documents that were included in the review. Inclusion criteria for the review cover types of documents including controlled trials, observational studies, qualitative studies, and case descriptions. Exclusion criteria for the study include the use of other treatments (injection with medications, radiotherapy) in addition to physiotherapy, and patients who had undergone spinal surgery with metal stabilization. Due to a small number of articles on conservative treatment in LSTV, the search was not limited to the language of the published article. In order to reduce duplication of original research summarized in this review, secondary sources were excluded. An attempt was made to complete the information for those articles that had gaps in the details of the LSTV patients described. Three emails were sent to the corresponding authors of publications. Only one response was received. Article titles and abstracts were initially screened for eligibility, and only then reviewed independently and fully analyzed (J.F., B.T.). Any disagreements arising in screening or data extraction were resolved through discussion between the authors. The primary outcomes concentrated on the effects of physiotherapy on pain reduction in LBP in LSTV patients. Secondary outcomes included the duration of therapy and type of physiotherapeutic interventions used. The flow chart of the study is shown in Figure 1.

Statistical methods

In the selection process of eight manuscripts presenting case studies, one non-randomized control study and only one randomized controlled study qualified for review. Due to the very small number of randomized controlled studies available in the literature, comprehensive evaluation of the effect of physiotherapy in patients with LSTV was not possible. This article presents a simple summary of the information available in the literature so far. The analysis was performed on all available data (including incomplete data) reported in the literature. If missing, standard deviation was imputed based on the rest of the studies. Only descriptive statistics were presented: number of observations, percentages, mean with 95% confidence interval (CI) or range. Calculation of an overall mean was performed using the ‘metamean’ function from the ‘meta’ package in R [27].

Assessment of risk of bias

Risk of bias assessment was performed using the Cochrane RoB 2 tool [28]. Assessment was performed only on studies comparing two interventions. Case studies included in the review were considered as “unclear risk”.

Results

General characteristics

The study included nine articles (2 original studies and 7 case reports) and one doctoral project presenting conservative treatment (various forms of physiotherapy) in 47 patients with LSTV [29–38]. The articles are mainly from Asian countries. They describe 32 patients from South Asian countries (India, Bangladesh) [29, 31, 34], 9 patients from East Asian countries (China, Korea) [33, 35], 5 patients from North America (USA, Canada) [30, 32, 36, 37] and 1 patient from Europe (Italy) [38]. Patients’ age range was 20–73 years, with an average of 39 years. The average duration of therapy was 3 weeks (3.09 ±1.99, min. 2 weeks, max. 12 weeks). Intervals between appointments and frequency of treatments varied (from one to 5 times a week). Most authors do not specify the duration of therapy, with single articles reporting an average duration of a therapy session of about 40–45 min [29, 33]. Patients had an average of 13 therapy sessions (min. 4, max. 21 meetings). The general characteristics of the studies included in the review are presented in Table II.

Table II

| Author(s), year, ref., country | n | Sex (F or M) Age (years) Profession (if described) | Castellvi classifications (if described) | Onyiuke Grading Scale | Duration of pain (if described) Radiculopathy (R) | Duration of therapy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ali et al. 2022 [29], Bangladesh | 1 | M, 22 Garments worker | II a left | II a | – R (+) hip | 6 weeks 21 sessions |

| Fectau et al. 2022 [30], USA | 1 | F, 15 Circus acrobat | II b | IV b | 4 year R (+) left lower extremity | 8 weeks 16 sessions |

| Lakhwani et al. 2022 [31], India | 1 | M, 54 Tailor | III b | III b | 5 years R (+) left lower extremity | 4 weeks 16 sessions |

| Jones 2018 [32], USA | 1 | M, 73 – | LSTV left | II a | 9 year R (+) left lower extremity | 12 weeks 12 sessions |

| Park et al. 2015 [33], Korea | 1 | F, 29 Nurse | LSTV (L6) | II a | – R (+) left lower extremity | 4 weeks 13 sessions |

| Angmo et al. 2015 [34], India | 30 | F and M, Age durations 20–55 | I a/II a | II a/b or III a/b | – R (+) or R (–) | 2 weeks 10 sessions |

| Chan et al. 2015 [35], China | 8 | 3 F : 5 M 39.25 ±14.8 | LSTV | LSTV | 8.25 ±6.36 months R (+) or R (–) | 4 weeks – |

| Muir 2012 [36] Canada | 1 | M, 29 – | II b | II b | – R (–) | 7 weeks 21 sessions |

| Muir 2012 [37] Canada | 1 | F, 51 Standing work | III a left | II a | 8 year R (–) | 6 weeks – |

| 1 | F, 62 – | III a left | III a | 2 year R (+) hip, left lower extremity | 4 weeks 4 sessions | |

| Brenner et al. 2012 [38], Italy | 1 | M, 22 Soldier | II a right | III a | 4 months R (+) hip | 2 weeks 4 sessions |

Types of physiotherapy interventions

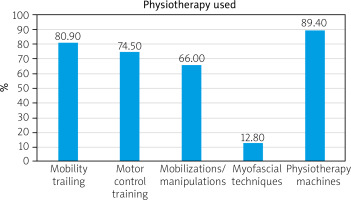

The types of interventions used according to their frequency are shown in Figure 2. All patients received elements of physiotherapy based on manual techniques and/or various forms of exercise. Mobility training included physiotherapy procedures such as directional preference exercises, range of motion (ROM) stretching, lumbar mobility, and strengthening. The term motor control training was used to described spine stabilization exercises, and the same method as Pilates or proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation. Therapies such as myofascial release therapy, soft tissue therapy, or trigger point therapy were described by one common name of myofascial techniques. Among all the cases described in the review, mobilizations and manipulations were the most commonly used manual therapy techniques. On the other hand, in terms of physiotherapy machines, hot packs and electrotherapy were mainly used. Only a few articles described the use of percussive massage therapy for muscles: rectus femoris and hamstring and myofascial decompression for spinal extensors, calf tissue restrictions, and posterior backline [30, 31].

Measurement tools

In the present study, the primary outcome measures by which clinical improvement was assessed used the following pain scales: Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) and Visual Analogue Scale (VAS). The Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) is used to measure pain influence on activity and participation in individuals with LSTV. Also, various other factors were analyzed to verify clinical improvement. The outcome measures that were used to assess clinical improvement in the articles analyzed are presented in Table III.

Table III

Outcome measures to assess clinical improvement in patients with lumbosacral transitional vertebrae after applied physiotherapy, based on reference information [28–37]

| Measuring tools | n | % | Before therapy | After therapy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VAS [30, 34–36] | 40 | 85.1 | 6.34 (mean)* (min. 5, max. 8) | 3.23 (mean)* (min. 0, max. 6) |

| NRS [31–33, 37–38] | 7 | 14.9 | ||

| ODI [33–35, 38] | 34 | 72.3 | 49.23 (mean) (min. 32, max. 68) | 29.16 (mean) (min. 4, max. 48) |

| Assessment of joint ROM** [31, 33, 36–38] | 13 | 27.7 | Improved ROM in all patients | |

| Return to work and/or PA [31–33, 38] | 4 | 8.7 | Return to work/PA in all patients | |

| FABQ-W [32, 38] | 1 1 | 2.1 2.1 | 28 8 | 23 – |

| FABQ-PA [32, 38] | 1 1 | 2.1 2.1 | 16 | 14 – |

| Sleep improvement [32, 33] | 2 | 4.3 | Better sleep in all patients | |

| Measurement of muscle multifidus thickness on CT [33] | 1 | 2.1 | Left: 572.09 mm2 Right: 479.84 mm2 | Left: 662.09 mm2 Right: 530.9 mm2 |

* The average pain value from articles that reported a range of pain scales “from – to” was calculated based on the maximum value of pain in the scale quoted.

** Range of motion was assessed using a spinal mouse (Idiag, Swiss) [33], goniometer [36, 38] or inclinometer [38].

CT – computed tomography, FABQ-W – Fear Avoidance Belief Questionnaire, the Work subscale, FABQ-PA – Fear Avoidance Belief Questionnaire, the Physical Activity subscale, NRS – Numerical Rating Scale, ODI – Oswestry Disability Index, PA – physical activity, ROM – range of motion, VAS – Visual Analogue Scale.

Different devices were used to assess the ROM, the studies were conducted using different techniques, and various spinal movements were assessed in various planes [30, 32, 35–38]. Two studies used the Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire (FABQ) for activity and work in analyzing return-to-work/physical activity outcomes [32, 38]. Measurements of the multifidus muscle were assessed using CT images of patients, which were performed before and after therapy [33].

In all analyzed studies, LBP assessment measures included VAS or NRS scales. Changes in VAS/NRS scores were observed when comparing pre- and post-therapy values (Table III). Also, changes in ODI scale values improved after therapy of LSTV patients, with mean post-treatment values showing a reduction. Most of the articles did not report whether and at what time after the end of therapy a recurrence of LBP was observed. Information on pain return concerned 3 patients [29, 36, 38] and appeared 1, 3, and 6 months after the end of physiotherapy.

Risk of bias in included studies

Assessment was performed only on case control studies. Case studies were considered as “unclear risk”. Risk analysis showed high overall bias, mostly due to lack of a proper randomization process, and selection of reported results (Table IV). In summary, the overall number of studies is small, and moreover all of them carry some risk of bias that might influence the results, and on that basis it is impossible to draw definite conclusions.

Discussion

To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first literature review presenting physiotherapeutic modalities and their effectiveness in patients with LSTV. Existing reviews describing LSTV to date have not included such a detailed analysis of physiotherapeutic management.

Physiotherapeutic strategies

The review shows that physiotherapeutic management can also be effective in reducing pain in LSTV patients, and that the time to LBP recurrence can persist for up to 6 months after the end of physiotherapy.

The number of studies and case reports in the literature on the treatment management (conservative and surgery treatment) of patients with symptomatic LSTV is sparse. Therefore, there is a lack of consensus on the treatment of LBP in LSTV patients [3]. The choice of treatment should ultimately be guided by a reliable clinical assessment and the patient’s specific condition. Undergoing surgery is considered the last line of treatment. Physiotherapy, ergonomic relief efforts, and other less invasive treatment options should be offered before the surgery is suggested [7].

In the management of LSTV patients with LBP, the different anatomical variants of the musculoskeletal system, functional factors and biomechanical differences must be taken into account, as deviations from the norm can lead to confusion and false assumptions in the diagnostic process and physiotherapeutic treatment. According to this review, mobility training, motor control training, and mobilizations were most commonly used in LSTV patients to reduce LBP. There is increasing evidence that in patients with LBP, exercises with educational programs can reduce the risk of LBP and its intensity [17]. Also important is early physiotherapy, which can improve a patient’s function and reduce pain [39]. Physiotherapy should be an important strategy for pain prevention in LSTV patients. Training should be comprehensive and individually adapted to the needs of the patients: training of the autochthonous muscles of the back, spine stabilization exercises, ROM stretching, lumbar mobility, exercises to strengthen the lumbar and quadriceps muscles and the abdominal muscles as a preventive measure.

Radiological diagnostics and implications for physiotherapy

Reliable radiological diagnosis in LSTV patients is important for treatment management. Bertolotti’s syndrome is characterized by variability, and clinical symptoms often correlate poorly with imaging findings [23]. The most common diagnostic errors observed relate to the inaccurate numbering of vertebrae [2, 3].

The presence of fatty infiltrates in analyzed muscles on CT imaging in patients with LSTV [17] previously has been described in relation to patients with reduced muscle activity or repetitive trauma. Such changes may result from mobility limitations and a higher incidence of bone fusion in LSTV [40] or may be due to the fact that LSTV itself is poorly understood in terms of other possible soft tissue changes. It was found that in patients with the presence of fatty infiltrates, proper training of the spinal stabilizing muscles can reduce this degenerative process [41–43]. Therefore, such preventive management also seems to be important in patients with LSTV, in whom increased fat infiltration is observed. Presumably, properly selected exercise training and exercise can also prevent early muscle degeneration.

Practical use of lumbosacral transitional vertebrae classification for physiotherapy

Lumbosacral transitional vertebrae are a frequently described clinical problem and occur in an average of 4–36% of patients with LBP [2, 3, 5, 7]. There are different classifications of LSTV [8–12]. The oldest and most common is Castellvi’s classification referring to the anatomical division of the defect [8]. The Onyiuke Grading Scale classification [11] seems useful for physiotherapy. This classification not only details the anatomical organization of the junction between the TP and SA in LSTV, but also takes into account the presence of vertebral lumbarization/sacralization as well as concomitant other spinal pathologies, and includes the presence of pain and/or radicular symptoms. Lumbarization/sacralization, on the other hand, alters the biomechanics of the lumbar spine and can affect the outcome of non-operative treatment of LSTV patients with LBP [44]. However, a reduced or increased number of lumbar vertebrae is rarely present in practice. According to Paik et al. [6] based on 8,280 lumbar spine radiographs analyzed, an increased or decreased number of lumbar vertebrae occurs in 2.6% and 8.2% of patients, respectively.

Low back pain in a patient with lumbosacral transverse vertebrae

In all studies analyzed, the main measurement indicator was pain assessment. The applied physiotherapy achieved a reduction in LBP as measured by various pain scales. However, LBP in LSTV can have different etiologies, which should be taken into account when building up the patient’s physiotherapy program.

Causes of pain in lumbosacral transitional vertebrae

Lumbosacral transitional vertebrae may contribute to the onset of lower back pain at an earlier age than in the general population [5, 45–48]. However, as LBP is prevalent in the population, identifying LSTV as the source of pain may be difficult. Discussions on the role of LSTV in LBP pathology have been ongoing for many years [49, 50]. According to the literature, LBP is more frequently observed in patients with LSTV than in patients without LSTV [51]. However, some studies have shown no significant difference in pain severity between patients with and without LSTV [3]. A number of studies have described the existence of pain in individuals with LSTV, but evidence on the exact mechanism of pain development is still unclear.

When analyzing the causes of pain, multifactorial etiology should be considered. In the pathogenesis of pain in LSTV patients, the following are mentioned [52]:

genetic factors:

functional abnormalities:

–abnormal loading of interarticular joints with secondary degenerative changes of the pseudo-joints (between the TPs and the sacrum, type II of the Castellvi classification) and/or adjacent motor segments,

–muscle imbalance due to asymmetry and changed mobility,

–secondary compression of nerve roots,

–impaired motor control due to pain and peripheral and central sensitization (CS).

Pain reduction after physiotherapy

The difficulty in physiotherapy for LSTV patients with LBP is due to the fact that patient populations are heterogeneous and may have different causes of pain. Physiotherapy represents a first-line treatment for chronic LBP [53]. In many studies of chronic LBP associated with various other spinal pathologies, intensity and disability were significantly reduced at short-term follow-up [54]. All the articles in this review described pain reduction to a higher or lower degree. Similarly, pain reduction was presented in the existing reviews independently of the treatment method used (conservative, injections or surgery) [2, 7, 55]. In a study by Santavirta et al. [56], the operatively treated LSTV patients had pain with a slightly better ODI pain score than patients with physiotherapy applied. However, regarding the total ODI, the results did not differ. As LBP in patients with LSTV is chronic and recurrent (including after surgical treatment [57]), therapeutic management strategies should focus not only on pain reduction but also on preventing its recurrence.

Recurrence of pain

Pain recurrence is a noted problem in patients with LSTV. This is due to the anatomical anomalies of the vertebral column itself, the different biomechanics, and other abnormalities that are associated with LSTV. When conducting therapy with such a patient, this must be taken into account. In this review, pain recurrence occurred with varying frequency, 1–6 months after therapy. However, due to incomplete data in most of the articles used in the review, far-reaching conclusions cannot be drawn. The problem of pain recurrence does not only concern cases of conservative treatment with LSTV but is also described in patients treated with GCs injections or radiofrequency ablations and those managed surgically. Unfortunately, in the literature covering the treatment of LSTV, the follow-up period was not always reported. In the Marks et al. study [58], 5 of 10 patients who had X-ray-guided injections of GCs and local anesthetics in the LSTV relapsed to their former pain level after one day to 12 weeks. According to Jain et al. [59], non-surgical treatment in LSTV patients had good pain relief lasting 3–6 months [59]. Nevertheless, the time until pain recurrence in operated patients is longer, being in the range of 12–24 months [57].

Coexistence of other spinal pathologies

The association of occurrence of LSTV with transitional vertebral discopathy for the first time by Stinchfield and Sinton [60] gave rise to contextual considerations regarding other coexisting conditions/anomalies of the lumbosacral transition region. LSTV-associated disorders reported in the literature include disc protrusion, nerve root canal stenosis, spondylolysis, sclerosis at pseudojoints, spondylolisthesis, and spina bifida [61–66]. These conditions can affect the patient’s function and pain. It is therefore important to consider them in the therapeutic management process. The relationship between LSTV and coexisting abnormalities is under discussion and not completely documented.

The presence of unilateral LSTV is associated with asymmetric loading and wear on the joints and may favor the development of degenerative changes within the presenting pseudoarthritic joints or segments adjacent to the LSTV [51]. Premature development of degenerative changes in patients with LSTV has been cited as one of the possible causes of LBP. An association between LSTV and disc herniation has been reported in the literature. Intervertebral disc levels are affected more frequently at the levels L3–L4 and L4–L5, especially in male patients with LSTV [67, 68]. Lumbosacral transitional vertebrae are related to disc herniation in adolescents as well [69], and L5 sacralization may contribute to intervertebral disc herniation in patients [67, 69]. On the other hand, type III according to the Castellvi classification (stiffening) may lead to consequences similar to those of the described adjacent segment disease (ASD) after lumbar or lumbosacral fusion [55].

Increased lordosis angle, which was observed in LSTV patients [13], may predispose to development of spondylolisthesis [70, 71]. On the other hand, the notion that sacralization may provoke spondylolisthesis is based on the theory that lack of or limited movement between the LSTV (L5) and the sacrum can lead to hypermobility and result in spine instability and consequently spondylolisthesis. However, this theory has not been confirmed in certain studies [66, 72]. Probable other anatomic variations, such as instability of the musculoskeletal system, may influence the occurrence of spondylolisthesis.

The co-existence of spina bifida occulta and LSTV has been reported in the literature. Unfortunately, the relationship between these defects has not been analyzed. The authors indicate that spinal mechanical instability due to spina bifida occulta can probably be compensated by the formation of an extra joint due to the LSTV [63].

Lumbosacral transitional vertebrae and conflict with anatomical structures

In addition, many authors note the possible conflict with nerve structures that is observed especially in Castellvi type II. Pseudarthrosis between the TP and the sacral ala was present on the side of compression with prominent new bone formation causing extra-foraminal compression of the exiting nerve root below the LSTV [73]. Evaluation of nerve root symptoms in patients with LSTV can be complicated by the accompanying variability of lumbosacral myotomes [56]. McCulloch and Waddell stated that a functional L5 nerve root always begins at the lowest mobile level of the lumbosacral spine [74]. If a sacralized L5 vertebral body is present, the L4 nerve root performs the usual function of the L5 nerve root; similarly, when a lumbarized S1 is present, the S1 nerve root acts as the L5 nerve root [75].

Central sensitization

When considering possible causes of LBP in LSTV patients, CS should be mentioned. No specific case describing CS in LSTV patients with LBP was found in the literature. Given the fact that pain in the lumbar region is most strongly associated with CS rather than that of other regions [76], CS should also be considered as a possible cause of LBP in LSTV patients. Furthermore, there is growing evidence that psychosocial factors are associated with treatment outcome and prolongation of LBP symptoms [77]. CS includes dysfunctions within the central nervous system in the spinal centers, as well as altered sensory processing within the brain, i.e. increased activity in areas known to be involved in the sensation of pain, i.e. the insula, the cingulate cortex, the prefrontal cortex, and the brainstem. The population of patients with CS is at higher risk of disability and has poorer pain management outcomes in terms of pharmacological and surgical interventions. Therefore, it is advisable to separate this group of patients from those without SC symptoms [78]. The presence of CS in LBP remains to be considered when the pain is localized in areas not associated with the original source of pain. It is continuous, persistent, and difficult for the sufferer to characterize. The pain is disproportionate to the nature and extent of the injury or pathology, is diffused in nature and variable in location, may be bilateral, and may be accompanied by allodynia and/or hyperalgesia [79]. The patient also shows clinical signs of other sensory hypersensitivity, such as smell, noise, etc.

Strengths and limitations of the study

Strengths of the study

The available reviews cover the different types of treatment used for Bertolotti’s syndrome. The reviews published to present physiotherapy in patients with this syndrome to date are usually based on 3 to 4 articles, which do not fully present an analysis of the effectiveness of such treatment used. This systematic review comprehensively and transparently evaluates the available evidence regarding physiotherapy management strategies for chronic pain control in patients with LSTV and LBP.

The authors were able to access a larger number of articles describing this topic, making the analysis appear more complete and detailed. This systematic review transparently evaluates the available evidence regarding physiotherapy management strategies for chronic pain control in patients with LSTV and LBP.

Study limitations

The small number of randomized controlled studies described in the literature may present some limitations of the review. In addition, the lack of detailed reports of the studies included in the analysis prevents a thorough analysis of the various relationships worsening or improving the treatment effect. The inclusion of more patients would require detailed reporting of the physiotherapy used in LSTV patients with LBP.

In addition, the scientific evidence shows the importance of collecting discussions on patient expectations such as the hope for the best possible outcomes, the expectation of tailored training with frequent follow-ups, activity levels, good dialogue and communication, etc. Obtaining such data from patients could be related to better recovery outcomes [80]. None of the articles included in the review contained data covering discussion of patients’ expectations. The inclusion of these aspects during implementation of the study would have provided a broader understanding of the specific topic.

The review only reports on physiotherapy management, but the lack of analysis of physiotherapy safety or the impact of LSTV on activities and participation is a notable limitation. Moreover, this review does not include other components of rehabilitation, such as occupational therapy, psychological support, or social and vocational activation. This is due to the fact that these areas are underrepresented in the reviewed literature. It would be worth considering performing a multicenter study of the use of comprehensive rehabilitation management in patients with this condition.

Undoubtedly, the inclusion of imaging techniques (e.g. electrophysiological testing, MRI, CT) in the analysis would provide a more detailed overview of potential factors that may influence treatment outcomes. However, a review of the research does not provide an analysis of all factors that could potentially influence clinical improvement after physiotherapy in LSTV patients with LBP.

Conclusions

Due to the heterogeneous patient population with LSTV and the different causes of pain, physiotherapy in chronic LBP can be difficult to apply and usually requires an individualized approach. Therapeutic management strategies should be a first-line treatment option in LSTV patients with LBP. In addition, physiotherapy remains an important management strategy for the prevention of LBP and is an important treatment option in clinical cases where surgery is contraindicated or the patient does not accept surgical management.

It is advisable to structure and systematize a physiotherapeutic treatment program for patients with LSTV that includes examination, diagnosis, scales used, and physiotherapeutic procedures applied. It is also important to monitor patients and follow-up evaluation that include analysis of specific scales in the period distant from the applied physiotherapeutic treatment.