Introduction

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic inflammatory multisystem disease of unknown etiology characterized by diverse clinical manifestations and a variable course and prognosis. The incidence of SLE ranges from 3.7 to 49.0 per 100,000 individuals with a predominance among women, particularly those of younger age [1]. Systemic lupus erythematosus has long been considered a prototypical immune complexes-mediated disease. However, it is now increasingly recognized as an acquired interferonopathy. Innate immune receptors, such as toll-like receptors (TLRs), detect pathogen-associated molecular patterns and initiate immune activation bridging the innate and adaptive immune responses. In lupus, TLR7 and TLR9 in particular are implicated, as they mediate the production of interferon α (IFN-α) by plasmacytoid dendritic cells upon activation by circulating immune complexes containing self-nucleic acid [2]. Neutrophils also play a critical role in SLE pathogenesis. Enhanced formation of neutrophil extracellular traps and increased neutrophil degranulation contribute to the release pro-inflammatory cytokines, including interferons (IFNs) [3]. Elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-6, IL-2, and IFNs in patients with SLE promote T helper 1 (Th1) differentiation and naïve T cell proliferation, ultimately leading to increased immunoglobulin G production by B cells [4]. Type I interferons, especially IFN-α, are considered central mediators driving the loss of cell tolerance and autoreactivity in SLE [5].

From a clinical standpoint, particularly in a disease as pathogenetically and clinically complex as SLE, there is a pressing need for therapies that act rapidly and effectively while maintaining an acceptable safety profile. Currently, available biologic therapies for SLE include rituximab, belimumab, and anifrolumab (ANF). Blocking the type I interferon signaling pathways has proven to be a highly effective therapeutic strategy. Anifrolumab is a fully human monoclonal antibody that targets subunit 1 of the type 1 IFN receptor (IFNAR1) [6], thereby preventing formation of the active IFNAR heterodimer.

However, data regarding the efficacy and safety of ANF in patients with severe SLE remain limited. The aim of this report is to share our clinical observations and experiences in treating patients with neuro-SLE, lupus nephritis (LN), and antiphospholipid syndrome-associated SLE (APS-SLE).

Material and methods

Ten patients with severe SLE were treated in the Rheumatology Clinic of the National Institute of Geriatrics, Rheumatology and Rehabilitation between 15 March 2024 and 20 April 2025. The diagnosis of SLE was established based on the clinical presentation, laboratory and imaging tests, and considering the American College of Rheumatology (ACR)/European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR) 2019 classification criteria of SLE [7].

Demographic, clinical, laboratory data, Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index 2000 (SLEDAI-2K) values, and the medical treatment of ten cases with severe SLE before ANF treatment are presented in Table I.

Table I

Summarized demographic, clinical, laboratory data, SLEDAI-2K values and medical treatment of ten cases with severe SLE before ANF treatment

[i] AE – adverse event, ANF – anifrolumab, APS – antiphospholipid syndrome, AZA – azathioprine, CLASI – Cutaneous LE Disease Area and Severity Index, CYC – cyclophosphamide, CysA – cyclosporine, dsDNA – double-stranded deoxyribonucleic acid, epi – epilepsy, GC – glucocorticosteroid, GFR – glomerular filtration ratio, HCQ – hydroxychloroquine, LIP – lymphocytic interstitial pneumonitis, MMF – mycophenolate mofetil, MTX – methotrexate, NPSLE – neuropsychiatric systemic lupus erythematosus, PGA – Patient Global Assessment, RTX – rituximab, SJC – swollen joint count, SLE – systemic lupus erythematosus, TJC– tender joint count, SLEDAI-2K – Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index 2000.

Patient No. 1, age 48 years, male, with third and fourth cranial nerve palsies and lupus headache with inflammatory lesions on brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), was admitted due to severe lupus flare (SLEDAI-2K = 16).

Patient No. 2, age 46 years, female, was admitted due to acute demyelinating inflammation of the second cranial nerve with necrotizing uveitis and orbital inflammatory pseudotumor (SLEDAI-2K = 25).

Both patients (No. 1 and No. 2) were treated initially with methylprednisolone (MP) pulses with mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) and cyclosporine (CysA), later changed to cyclophosphamide (CYC) (up to 6 g). Despite aggressive treatment, cranial nerve palsies and headaches were recurring during reduction of MP doses below 16 mg/day.

Three patients with LN were admitted due to severe flare of SLE: No. 3, age 47 years, male, with class III/IV nephropathy; No. 4, age 22 years, female, with class II/V LN; and No. 2, with neuropsychiatric lupus and class III LN.

Patient No. 3 presented a rapid rise of creatinine levels from 0.7 mg/dl glomerular filtration rate [glomerular filtration ratio (GFR) > 90 ml/min] to 2.7 mg/dl (GFR 23 ml/min) in 1 month with concomitant nephrotic syndrome and proteinuria 3.4 g/day (SLEDAI-2K = 25). The patient was started on MP 1 mg/kg/day and CYC (total 6 g). Despite treatment, we observed a rise of creatinine to 3.3 mg/dl.

In the second case (patient No. 4) we observed initially a rise in proteinuria to 1 g with a concomitant rise in creatinine levels from 0.6 mg/dl (GFR > 90 ml/min) to 1.1 mg/dl (GFR 54 ml/min) (SLEDAI-2K = 16). The patient was treated with CysA (250 mg/day), MMF (3 g/day) and MP, but no change in proteinuria/creatinine level was observed. Patient No. 4 was additionally diagnosed with lupoid hepatitis [aspartate transaminase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) elevated 5 × above the normal range].

Patient No. 2 additionally presented 1.5 proteinuria per day and creatinine 1.1 mg/dl, GFR 54 ml/min with no improvement after pulses of MP followed by MP orally 16 mg/day, CYC (total dose 7 g), MMF 3 g/day, and CysA 250 mg/day.

Patient No. 5, age 37 years, female, additionally had thrombocytopenia 20,000 platelets/ml and obstetric antiphospholipid syndrome (oAPS). There was no improvement after pulses of MP followed by oral MP 16 mg/day and CysA 250 mg/day.

Patient No. 6, age 57 years, female, had comorbid porphyria and primary hemochromatosis with severe skin lesions with ulcerations (CLASI 31 points) attributed to SLE based on skin biopsies.

Patient No. 7, age 37 years, male, was additionally diagnosed with Raynaud’s syndrome and lymphocytic interstitial pneumonitis (LIP).

Bioethical standards

The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines and was approved by the Bioethics Committee of the National Institute Geriatric, Rheumatology and Rehabilitation, Warsaw, Poland (consent N KBT-2/6/2025).

All the patients provided written consent to participate in the study and authorization to use their health data. All patients agreed to be treated with ANF.

Results

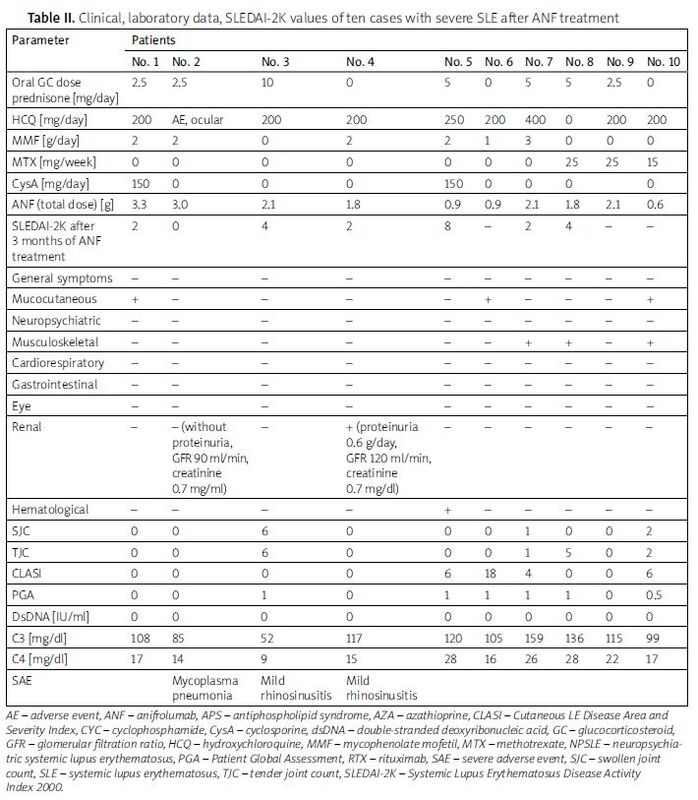

Table II presents data of patients after ANF treatment. Patients were treated with ANF for 6 to 15 months. No serious adverse event was noted in our group of SLE patients.

Table II

Clinical, laboratory data, SLEDAI-2K values of ten cases with severe SLE after ANF treatment

[i] AE – adverse event, ANF – anifrolumab, APS – antiphospholipid syndrome, AZA – azathioprine, CLASI – Cutaneous LE Disease Area and Severity Index, CYC – cyclophosphamide, CysA – cyclosporine, dsDNA – double-stranded deoxyribonucleic acid, GC – glucocorticosteroid, GFR – glomerular filtration ratio, HCQ – hydroxychloroquine, MMF – mycophenolate mofetil, MTX – methotrexate, NPSLE – neuropsychiatric systemic lupus erythematosus, PGA – Patient Global Assessment, RTX – rituximab, SAE – severe adverse event, SJC – swollen joint count, SLE – systemic lupus erythematosus, TJC – tender joint count, SLEDAI-2K – Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index 2000.

After ANF treatment, all patients improved clinically and showed a reduction in SLEDAI-2K in comparison with the previous value.

In both cases with neuropsychiatric lupus (patients No. 1 and No. 2), we initiated additional treatment with ANF. After 3 months of treatment, patients achieved full remission of neuropathy. Also, we managed to reduce MP doses below 4 mg/day. Patient No. 2 was ultimately without orbital inflammation. We observed cessation of proteinuria, and the patient achieved low lupus disease activity.

In the case of patient No. 3, due to aggressive disease progression, we initiated treatment with ANF at full dose. After one month, we observed a rapid improvement in SLEDAI-2K to 6 and a decrease in creatinine level to 1.3 mg/dl (GFR 58 ml/min) with normalization of proteinuria.

In patient No. 4, after addition of ANF we observed a decrease of creatinine levels to 0.7 mg/dl (GFR > 90 ml/min) and proteinuria cessation (SLEDAI-2K = 7). Additionally, patient No. 4 showed normal AST and ALT values.

In patient No. 7, we observed stabilization of pulmonary lesions and major improvement in the skin involvement.

Patient No. 5 showed improvement in SLEDAI-2K and an increase in platelet count to 100,000/ml.

We observed 3 side effects during ANF therapy: mild rhinosinusitis in 2 patients and Mycoplasma pneumonia in 1 patient.

Discussion

Randomized, placebo-controlled phase 3 (TULIP-1 and TULIP-2) trials have shown efficacy and safety of ANF during treatment of patients with SLE [8–11]. In these trials, including 809 SLE patients, intravenous administration of ANF 300 mg every 4 weeks was associated with clinical improvement, as evaluated by British Isles Lupus Assessment Group (BILAG)-based Composite Lupus Assessment (BICLA) and the SLE Responder Index (SRI) [8–11]. Patients also reduced glucocorticosteroid (GC) daily doses, and showed improvements in skin disease activity, active joint counts, and flare rates [7–10]. To date, many real-world observational studies have supported the efficacy and safety of ANF treatment in SLE patients [12–15].

In a recent issue of Lupus, Marques-Gomez et al. [16] reported a successful add-on therapy with ANF to the conventional treatment of chronic demyelinating polyneuropathy in SLE. Anifrolumab is a new emerging therapeutic option in SLE, yet data on its effectiveness in neuro-SLE and LN are scarce. Therefore, the authors’ contribution on this topic is important, as both manifestations are considered among the most severe [17]. Furthermore, we report 4 more cases (2 neuro-SLE, 1 neuro-SLE + LN and 2 LN) in which ANF demonstrated effectiveness.

A Japanese study [12] was based on real-world clinical practice from the LOOPS registry. It was a retrospective observational study, which included 45 SLE patients who started ANF therapy. The patients were divided into 2 groups: the non-LLDAS (Low Disease Activity State) achievement group and a minor flare group. In both groups, GC doses and the SELENA-SLEDAI score significantly decreased by week 26 after initiating ANF therapy, and about 90% of patients remained on therapy.

Another very interesting study was a multicenter, retrospective study involving 9 Italian SLE referral centers participating in a program for the use of ANF in adult patients with active SLE in whom all the other available treatment choices failed, were not tolerated, or were contraindicated [13]. A total of 26 SLE patients were enrolled. At 6 months, 50% of patients were in remission, and 80% were in LLDAS. A significant reduction in the mean GC daily dose was observed, starting from week 4. Overall, 4/20 patients with at least 24 weeks of follow-up (20%) were considered non-responders.

A study from Denmark [14] showed that ANF therapy improved subjective patient experience of treatment effects and implications for patients’ health-related quality of life (HRQoL). Data were collected from 16 patients with SLE (treatment duration 62–474 days). Patients reported a significant impact of the disease on daily life before treatment: day-to-day activities, social life, emotional aspects, physical activity, concentration/memory, work/employment, and family/romantic relationships. The authors also observed a decrease in disease activity after treatment initiation with a concomitant reduction in the use of GCs. A Greek study on multi-refractory skin disease reported efficacy of ANF in 18 SLE patients with active skin involvement, with a mean CLASI of 13.9 [15]. Flouda et al. [15] stated that ANF is highly effective in various skin manifestations of SLE, even prior to failure of multiple treatments.

In our cohort, an interesting improvement in cranial neuropathy and in the central nervous system involvement was observed. Similarly to the TULIP-2 extension trial [18] in our cases, addition of ANF significantly reduced the time to reach remission. Anifrolumab showed an acceptable safety profile; no major severe adverse event (SAE) was observed.

Interestingly, in patients with neurological manifestations of SLE, we observed the main improvement in terms of cranial nerve neuropathy. In patient No. 1, fourth and sixth cranial nerve symptoms improved, but polyneuropathy symptoms remained unchanged. Also, signs of inflammatory necrotizing uveitis with bilateral second nerve inflammation in patient No. 2 improved. As neuro-SLE was among the exclusion criteria in all available clinical trials to date, there is a paucity of data on efficiency of ANF in neuro-SLE. Our observation is among the few available.

Similarly to TULIP-1 and TULIP-2 with extension trials, ANF has shown an acceptable safety profile, as no major SAE were observed [9–11, 18]. Furthermore, we did not observe any herpes or varicella reactivations or primary infections despite several risk factors for infections during flare of the disease. In 3 cases we observed some adverse events: 2 patients presented mild rhinosinusitis and 1 case of Mycoplasma pneumonia infection. However, because the treatment was administered in the winter infection season, the causality of ANF therapy is questionable.

Conclusions

Building on the evidence from international studies, we report our single-center experience of 10 severe SLE cases with neuro-SLE, LN, and APS-SLE. Our retrospective observational study underlines very good results of ANF therapy in severe SLE cases, not responding to previous therapy with high doses of GC and immunosuppressive agents. In our observations, similar observations were made. We hope that more of our patients may benefit from it in the future.