Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic systemic autoimmune disease characterized by prolonged synovitis, systemic inflammation, and the formation of autoantibodies. Joint degeneration, disability, reduced quality of life, cardiovascular diseases, and other comorbidities are all consequences of uncontrolled active RA [1]. According to current guidelines, as soon as RA is diagnosed, treatment with disease-modifying antirheumatic medications (DMARDs) should begin [2].

According to de Klerk and van der Heijde [3], adherence is the process by which patients take their medications as directed, which includes starting the medication, following the prescribed regimen, and stopping the medication [4]. Noncompliance is related to poor response to or failure of therapy, worsening or return of the condition, and wasteful treatment adjustments [5]. In the management of chronic illnesses such as RA, noncompliance with pharmacologic therapy is a crucial concern. Drug adherence is considered to be crucial for effective treatment. Non-adherence is a major problem for patients with chronic rheumatic diseases such as RA [6]. Medication adherence refers to the extent to which patients follow medical professionals’ recommendations regarding the frequency, dose, and timing of drug administration [7].

Noncompliance with medication results in poor disease control, increased morbidity, and repeated hospitalization, all of which raise the use of health resources [8, 9]. Enhanced comprehension of the effects of treatment adherence on RA patients and the discovery of potential adherence predictors will enable the creation of adherence-promoting tactics.

Research on adherence to treatment in patients with RA is rare in Kurdistan Region, Iraq, and the Middle East. One study conducted in Egypt reported that 65.1% of patients were highly adherent to their treatment, followed by 26.0% with middle-level adherence [10], and 40.9% in Iran [11]. The purpose of this study was to determine the prevalence of medication adherence and its related factors in patients with RA at the Specialized Center of Rheumatic Diseases and Medical Rehabilitation in Duhok City.

Material and methods

Study design

A cross-sectional study design was employed in 91 patients with RA at the Specialized Rheumatology Center in Duhok City in Kurdistan Region. Patients who attended the mentioned rheumatology center and were diagnosed with RA by a rheumatologist were included in this study. In this regard, we tried to reach the RA patients by phone.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

This study included adult patients aged 18 years and above who had been diagnosed with RA. Patients were included regardless of their gender, socioeconomic status, or disease duration. Patients who could not be contacted due to missing or incorrect contact information were excluded from the study. In addition, patients with cognitive impairments that hinder their ability to understand or participate were not included. 17 patients were excluded for various reasons: did not answer (n = 4), incomplete information (n = 5), did not have time (n = 2), were not taking any medication (n = 2), incomplete responses (n = 2), did not complete interview (n = 1), and experiencing depression (n = 1).

Setting

The Specialized Center of Rheumatic Diseases and Medical Rehabilitation in Duhok City is a standalone tertiary center for diagnostic and treatment services for patients with rheumatic illnesses and rehabilitation services. There are no private medical centers for the treatment of rheumatic diseases in the Duhok region. Therefore, we are confident that our sample is as representative as possible of patients from this area.

Data collection and measures

To collect the general and medical characteristics of the RA patients in this region, we created a Google Form. Then we called the patients one by one, based on the available medical records of the center. We obtained some medical and general information from the medical records, and the remaining information was obtained through phone calls. The information was entered into the Google Form and later was downloaded as an Excel file. The following information was included in the predesigned questionnaire: demographics, medical history, medication use, perceptions of treatment and side effects, and access to treatment. The disease severity of the patients was determined by a doctor and recorded in the medical records as the Disease Activity Score in 28 joints score [12].

Statistical analyses

The demographic and medical features of the patients are reported as mean (standard deviation, SD) or number (%) as applicable. Adherence of the patients to the treatment is presented as the number and percentage. The associations of adherence to the treatment with the patients’ characteristics were examined using the Pearson χ2 test. The predictors of adherence to the treatment were determined using binomial logistic regression. The significance level was set at p < 0.05. The statistical calculations were performed using JMP Pro 17.1.0. (JMP, Version 14.30. SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, 1989–2023).

Bioethical standards

Ethical approval of this study was obtained from the health ethics committee of the Kurdistan Board for Medical Specializations and Duhok Directorate General of Health, registered on 30 October 2024 under no. 30102024-9-29. The patients were free to decline participation in the study and had the right not to answer any questions.

Results

The mean age of the RA patients (n = 91) was 49.70 [standard deviation (SD): 11.09], aged between 20 and 82 years. The patients were in different age groups, but mostly between 40 and 69 years (79%), and 79% were female. The patients had different educational levels. They were mostly married (91%) and unemployed (73%). The patients had different monthly incomes. Most of the patients had been diagnosed with RA for more than 10 years (42%), followed by 2–5 years (32%). The patients had different disease severity, including mild (20%), moderate (46%), and severe (35%), and more than half (53%) had other chronic diseases, such as hypertension and diabetes (Table I). The study showed that RA patients who were satisfied with the treatment were more likely to adhere to the treatment (full adherence: 84% in very satisfied patients, 0.0% in unsure, 50% in satisfied patients; p = 0.0003). Adherence to the treatment in patients with RA was not associated with other medical or general factors (not shown in the tables).

Table I

General and medical characteristics of the patients with RA

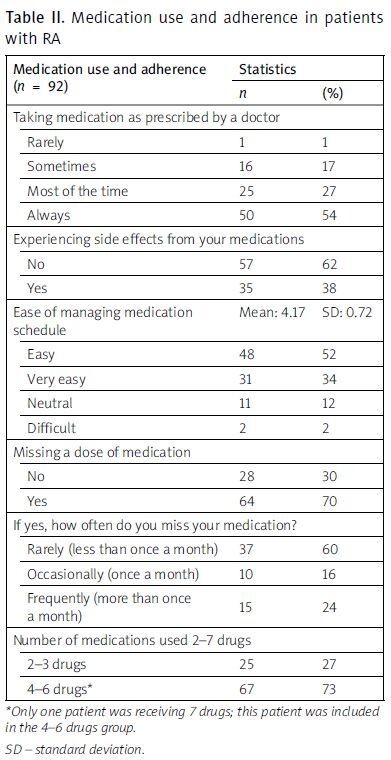

The study showed that most of the patients always took their medications (54%), followed by those who took them most of the time (27%), and sometimes (17%). Only one patient took their medications rarely (1%). The study found that 38% of the patients experienced some kind of side effects, mostly epigastric pain (51%), hypertension (6%), oral lesions (6%), and some other rare side effects. The patients had different management levels of medication schedules. Most of the patients found that managing the medication schedule is easy (52%) or very easy (34%). Only 2 patients found it difficult to manage their medication schedule. The patients reported that 30% missed a dose of medication, including rarely (60%), occasionally (16%), or frequently (24%) (Table II).

Table II

Medication use and adherence in patients with RA

| Medication use and adherence (n = 92) | Statistics | |

|---|---|---|

| n | (%) | |

| Taking medication as prescribed by a doctor | ||

| Rarely | 1 | 1 |

| Sometimes | 16 | 17 |

| Most of the time | 25 | 27 |

| Always | 50 | 54 |

| Experiencing side effects from your medications | ||

| No | 57 | 62 |

| Yes | 35 | 38 |

| Ease of managing medication schedule | Mean: 4.17 | SD: 0.72 |

| Easy | 48 | 52 |

| Very easy | 31 | 34 |

| Neutral | 11 | 12 |

| Difficult | 2 | 2 |

| Missing a dose of medication | ||

| No | 28 | 30 |

| Yes | 64 | 70 |

| If yes, how often do you miss your medication? | ||

| Rarely (less than once a month) | 37 | 60 |

| Occasionally (once a month) | 10 | 16 |

| Frequently (more than once a month) | 15 | 24 |

| Number of medications used 2–7 drugs | ||

| 2–3 drugs | 25 | 27 |

| 4–6 drugs* | 67 | 73 |

Most of the patients had regular access to prescribed medications (60%). Different factors were reported to have impacts on access to medications, including the cost of medication (78%), availability of medication at the pharmacy (27%), distance to the pharmacy/health center (14%), transportation issues (5%), and other factors (17%). Fifty-eight percent of the patients visited the rheumatologist every 2–3 months, followed by every month (30%), every 6 months (2%), and when necessary (9%). Most of the patients were satisfied (67%) or very satisfied (21%). The patients had a good or very good understanding of the treatment plan. Most of the patients found that the current treatment was effective in controlling the disease symptoms. The patients reported that the side effects were significant barriers to continuing treatment (26%). We found that 39% were interested in receiving additional support to improve adherence (Table III). Binary logistic regression showed that satisfaction is the only predictor of adherence to treatment in RA patients (p = 0.00006) in this study (not shown in the tables).

Table III

Access to treatment in patients with RA

Discussion

This study showed that most of the patients adhered to the treatment, whether mostly or sometimes. The patients experienced some kinds of side effects. A percentage of the patients missed a dose of medication. The patients had some kinds of barriers to treatment, including the cost of medication, availability of medication at the pharmacy, distance to the pharmacy/health center, transportation issues, and other factors. The study showed that most of the patients were satisfied with the treatment and found the current treatment to be effective. The patients reported that the side effects were significant barriers to continuing treatment.

Some other studies have been conducted in Middle Eastern countries. For example, 65.1% were reported to show high adherence to the treatment in Egypt [10], 40.9% in Iran [11], 30.2% were consistently compliant in Turkey [13], and 56.7% in Jordan [14]. However, different adherence rates have been reported in developed countries, for example, 90.4% in South Korea [15], 79% in Spain [16], and 87–95% in Canada [17].

Various factors have been reported to be associated with non-adherence in RA patients. The World Health Organization classified the factors associated with non-adherence into the following five domains [7]; socioeconomic factors; healthcare system factors; condition-related factors; therapy-related factors; and patient-related factors. In terms of sociodemographic factors, age, gender, education, tobacco use, socioeconomic status, living situation, marital status, and presence of children were not unequivocally related to adherence. We did not find a significant association between treatment adherence and age in this study. Some studies reported that older patients have better adherence, while others have reported that younger patients have better adherence to treatment [8]. However, the association between age and nonadherence or adherence may also be influenced by confounding factors such as multiple comorbidities and complex medical regimens (which are both often associated with increased age).

A good patient-provider relationship seems to improve adherence [18], whereas poorly developed health services with inadequate or nonexistent reimbursement by health insurance plans negatively affect adherence [19]. Many therapy-related factors could potentially affect adherence; none of these factors (class of medication, drug load, the immediacy of beneficial effects, and side effects) were adequate predictors for non-adherence in RA [3, 20]. Despite this, a review of studies in non-RA patients confirmed that the prescribed number of doses per day and the complexity of the regimen were inversely related to compliance. Simpler, less frequent dosing regimens resulted in better compliance across a variety of therapeutic classes [21]. We did not find a significant association between adherence and the number of medications in this study, possibly because most of the patients received many medications.

Regarding patient-related factors, patients seem to adhere better when the treatment regimen makes sense to them: when the treatment seems effective, when the benefits seem to exceed the risks/costs (whether financial, emotional, or physical), and when they feel they have the ability to succeed at the regimen [18, 22]. We did not find a significant association between adherence to the treatment and feelings of the patients when the treatment seemed effective. Some other factors have been reported to be associated with treatment adherence, such as occurrence of adverse events, while a higher level of education was associated with the risk of non-adherence due to an absence of RA symptoms [15].

Satisfaction with the quality of care was the only predictor of adherence to the treatment in RA patients in our study. Patients’ satisfaction with therapy has an impact on medication adherence, treatment continuation, and future treatment choices [23, 24]. Satisfaction is also closely associated with patients’ treatment expectations [25].

Strengths and limitations of the study

The strength of the study is that we tried to include as many patients diagnosed with RA as possible. However, some patients were not included in the study due to a lack of information in their medical records.