Introduction

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) is a non-infectious, autoimmune inflammatory disease of the joints, which is the most common rheumatic disease occurring in childhood, more often in girls, and the aetiology remains unclear at present (genetic predisposition, exposure to stress, the influence of viruses and sex hormones are taken into account) [1–4]. The division of JIA subtypes according to the International League of Associations of Rheumatology (ILAR) is as follows: systemic arthritis, oligoarthritis, polyarthritis (rheumatoid factor [RF]-positive), polyarthritis (RF-negative), psoriatic arthritis (PsA), enthesitis-related arthritis (ERA) and undifferentiated arthritis [3]. The symptoms common to all types of JIA are primarily stiffness, pain, and limitation of movement in the affected joints, while the individual types of JIA differ in, among other things, the severity of systemic symptoms, such as fever (mainly in the case of systemic JIA), symmetry of the affected joints (usually asymmetric in oligoarthritis JIA and polyarthritis RF-negative JIA and symmetric in polyarthritis RF-positive JIA), and uveal involvement (characteristic in oligoarthritis JIA) [4]. Diagnostics involves taking a medical history and performing a physical examination, imaging studies, and laboratory tests including, among others, inflammatory markers, RF, and antinuclear antibodies (ANA) [5, 6]. To make a diagnosis of JIA, the following criteria must be met: age of onset before the age of 16, at least 6 weeks of arthritis, and exclusion of other causes of arthritis [7]. An important role in treatment is played by interdisciplinary patient care, which includes rehabilitation, psychology, pharmacotherapy: using non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) such as methotrexate, glucocorticosteroids (GCs) and biologic drugs (for example, adalimumab, rituximab, tocilizumab, anakinra) [8–11]. An important issue concerning JIA is the coexistence of hormonal and metabolic disorders, such as Cushing’s syndrome (CS), Hashimoto’s disease (HD), type 1 diabetes (T1D), growth disorders and hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis disorders.

Cushing’s syndrome is primarily characterized by elevated cortisol levels, and its symptoms include obesity, diabetes, menstrual disorders, acne, hirsutism, stretch marks and mood changes [12]. The causes of its occurrence include hormonally active tumours, adrenal hyperplasia and long-term use of GCs (which may be important in the context of JIA) [13]. Hashimoto’s disease is an autoimmune inflammation of the thyroid gland that may be the cause of its hypothyroidism, which leads to complications in the form of weight gain, low mood and other hormonal disorders, such as irregular menstruation [14]. Another autoimmune disease that may occur with JIA is T1D, and hyperglycaemia contributes to increased inflammation, which in turn exacerbates the symptoms of JIA [15, 16]. Hashimoto’s disease, T1D and JIA are autoimmune diseases that tend to co-occur with each other, so after diagnosing one of them, it is important to keep this in mind and regularly monitor the patient’s condition in this respect [15–17]. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis is characterized by inflammation, problems with the musculoskeletal system and hormonal disorders that are a possible side effect of medications taken, which contribute to growth disorders [18]. The HPA axis functions on the principle of negative feedback. The hormones involved are primarily corticoliberin, adrenocorticotropic hormone and GCs, and in the context of JIA, close attention should be paid to the side effect of GCs, which is the suppression of this axis [19]. This article aims to analyse the co-occurrence of JIA with other autoimmune diseases of the endocrine organs, as well as with hormonal disorders that are an iatrogenic effect of drugs used in JIA therapy.

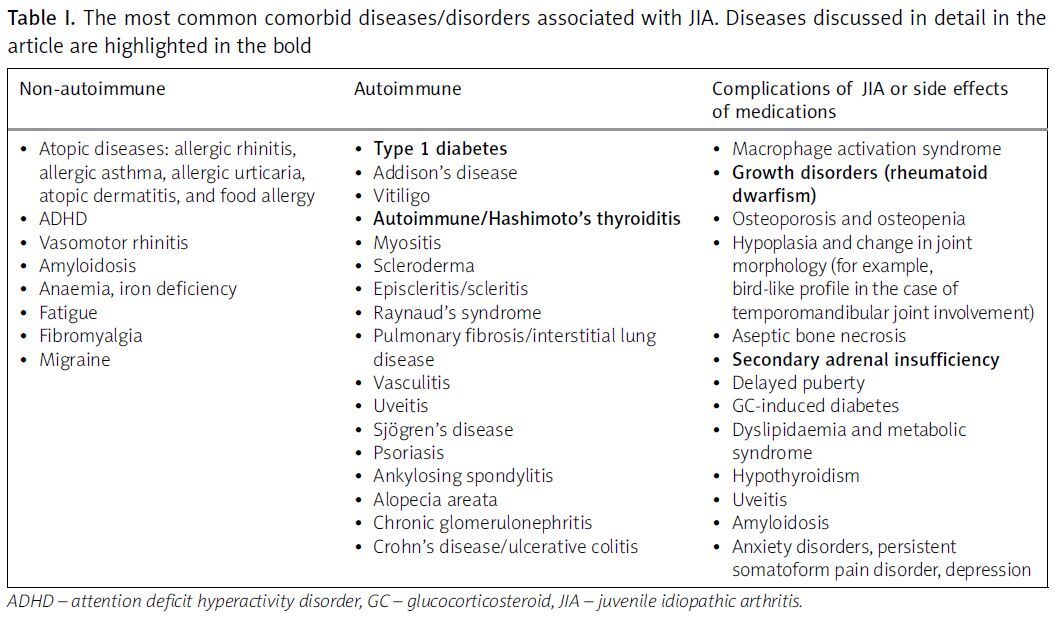

The authors also summarise the most commonly coexisting paediatric conditions in patients with JIA (Table I).

Table I

The most common comorbid diseases/disorders associated with JIA. Diseases discussed in detail in the article are highlighted in the bold

Type 1 diabetes and juvenile idiopathic arthritis

Type 1 diabetes is the most frequently occurring chronic metabolic disease of childhood. The presence of one autoimmune process increases the likelihood of developing additional autoimmune diseases. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis, though not the most common of them, is manifested by non-characteristic clinical features, which may postpone the diagnosis. This is a common reason for misdiagnosis and may confer a risk of inadequate treatment. The prevalence of JIA in patients with T1D is significantly greater (0.19%) than in the general population (0.05%) [20]. The coexistence of a few autoimmune diseases in one patient suggests that these conditions could have a common genetic background. The human leukocyte antigen (HLA), CTLA4, and PTPN22 as T-cell activation regulators are suspected of playing a crucial role in autoimmunity processes; i.e., the aberrant function of the molecules encoded by them are suspected to be responsible for the development of autoimmunity [21].

In most reported patients, diabetes developed first, whereas juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (RA) was diagnosed afterward, sometimes followed by other autoimmune diseases.

The likelihood of T1D occurrence appears to be slightly higher before JIA manifestation and without DMARDs therapy after JIA onset [20]. Surprisingly, haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) was found to be somewhat lower in children with JIA, presumably because of a more intensive treatment or a latent haemolysis caused by the inflammation [15].

Significant problems of paediatric patients with T1D are maintaining a stable glucose blood level and managing acute complications (hypo- and hyperglycaemia). Since hyperglycaemia and glucose variability are acknowledged pro-inflammatory conditions [22], it is crucial to avoid glycaemic fluctuations in JIA patients, to prevent exacerbation of inflammation, which may hinder the treatment of arthritis [16].

Interestingly, administration of biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) in some JIA cases is associated with a significant improvement of HbA1c and better long-term metabolic control of diabetes. Patients receiving biologic DMARDs for JIA require less insulin therapy for diabetes [20]. Moreover, DMARD therapy is suggested to prevent T1D development in patients with RA. Therefore, it could be an argument for starting biologic DMARD therapy early in the course of JIA management to potentially ameliorate the development of other autoimmune disorders [23].

It is extremely difficult for a young person to cope with one chronic disease, let alone two or more [16]. Psychological support can improve diabetes metabolic control and consequently affect the patient’s well-being and quality of life in a long-term perspective [24]. For this reason, the clinical psychologist should be included in the interdisciplinary team taking care of such a patient. The optimal pattern for the multidisciplinary service encompassing paediatric rheumatology, diabetes care, and the transition schedule between paediatric and adult care is an important issue to consider as well [20].

Cushing’s syndrome

Cushing’s syndrome is caused by prolonged exposure of the body to high levels of GCs in the blood [25, 26]. There are two types of CS: endogenous, in which cortisol is produced by the adrenal glands, and exogenous, in which the patient uses GCs [13, 26, 27]. If these are prescribed by a physician for therapeutic purposes, it is referred to as iatrogenic CS. The true incidence of CS is not known, as it is influenced by the nationality of the population and the frequency of GC use within that population [13]. Nevertheless, in order to illustrate the scale of the problem with the incidence of CS, some data on the subject will be presented. According to Guarnotta et al. [25], approximately 0.7–2.4 new cases of CS occur per million people annually, with about 10% of these cases occurring in paediatric age. In another study by Bavaresco et al. [12], the annual incidence of endogenous CS was estimated to be 2–8 cases per million people. Meanwhile, Tatsi et al. [28] stated that endogenous CS occurs in about 3–50 people per million per year, with 6–7% of all cases being paediatric patients [28]. On the other hand, there is a consensus in the medical community that the most common form of CS is iatrogenic CS, and that it is a frequent phenomenon in medicine [13, 26, 28, 29]. The prevalence of GC use for the treatment of various diseases affects 2–3% of the population [27]. Furthermore, among chronic diseases, the most common reasons for the use of GCs are rheumatological diseases and bronchial asthma [12]. Importantly, regardless of the method of GC administration, therapy with these medications can lead to the development of iatrogenic CS [13]. On the other hand, GCs are one of the main groups of drugs used in the treatment of JIA [30] . More precisely, they are used in the following subtypes: oligoarticular, polyarticular, systemic onset, and ERA [31]. Therefore, GCs are used in most subtypes of JIA. They can be administered systemically, intra-articularly, or injected at the entheseal site. In the case of the oligoarticular onset subtype, intra-articular GC injections are recommended [18]. When encountering a patient with CS, it is very important to determine its exact cause. Both endogenous and exogenous causes can occur simultaneously. Although very rare, such a situation has already been described [30]. This case concerned a 23-year-old female patient with JIA who was treated with oral triamcinolone at a dose of 4 mg. During this treatment, she had persistently elevated serum cortisol levels and the presence of large, nodular adrenal glands. She was ultimately diagnosed with primary pigmented nodular adrenocortical disease (PPNAD) as well as iatrogenic CS. Differentiating between these two types of CS can be facilitated by the fact that symptoms of hyperandrogenism, including hirsutism, although they can occur in exogenous CS, more strongly suggest an endogenous cause [25, 30].

Autoimmune diseases

According to a systematic review from 2024, no direct association was found between the molecular basis of JIA and other autoimmune diseases (ADs) [32]. It is suspected that the pathogenesis of JIA may be attributed to a combination of genetic, environmental, and hormonal factors. These factors induce an autoreactive immune response of T and B lymphocytes to autoantigen, which manifests as the accumulation of activated memory cells in the synovium [33]. Numerous studies have demonstrated the frequent co-occurrence of various ADs in children and adolescents with JIA [20, 33–36]. Several associations have been detected between human leukocyte antigen (HLA) alleles and JIA, RA, celiac disease (CD), and T1D. A study that examined the alleles and genotypes of JIA patients and healthy controls revealed a significant correlation between JIA and variants in certain regions of TNFAIP3, STAT4, and C12ORF30, which have been associated with other ADs, such as RA and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) [37]. Furthermore, the presence of comorbid AD in individuals with JIA has a detrimental effect on their quality of life, resulting in increased disability and mortality [34, 35]. The strongest association has been described between rheumatic diseases and thyroiditis [33].

Tronconi et al. [36] examined 79 patients with JIA. They found that 12 patients had at least one AD associated with JIA and among these, 4 patients suffered from two ADs. Eight patients (10.1%) had autoimmune thyroid disease (AITD), one was affected by Graves’ disease (GD), 5 had positive anti-thyroid peroxidase (anti-TPO) and/or anti-thyroglobulin (anti-TG) antibodies with normal thyroid hormones and thyroid-stimulating-hormone (TSH) levels, and 2 patients had subclinical hypothyroidism. No correlation between JIA subtype and AITD was noted. The mean age at diagnosis of AITD was 13.2 years, and only one patient developed AITD before JIA. The cumulative incidence of AITD was 36%. Celiac disease was present in 3 patients, 1 had alopecia, 1 had T1D, and 3 suffered from psoriasis [36]. A higher incidence of T1D among JIA patients compared to the general population (p < 0.001) was reported by Schenck et al. [20]. The likelihood of developing T1D appeared to be slightly higher before the onset of JIA and without disease-modifying antirheumatic therapy after the onset of JIA [20]. A cross-sectional study by Simon et al. [35] showed that ADs were more common in patients with JIA compared with a matched cohort of patients with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Among patients with JIA aged < 18 years, the highest odds ratios (ORs) were observed for Sjögren’s disease [35]. Another study by Lovell et al. [34] found that JIA patients with additional AD or comorbidity were significantly older at the time of onset and diagnosis of JIA compared with the control group. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis patients with additional AD or comorbidity were prescribed significantly more nonbiologic and biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, GCs, and NSAIDs, which may indicate a more severe disease course. Of the 26 autoimmune and related diseases assessed, 14 (chronic urticaria, T1D, Addison’s disease, vitiligo, autoimmune/HD, myositis, AD not elsewhere classified, scleroderma, episcleritis/scleritis, Raynaud’s syndrome, pulmonary fibrosis/interstitial lung disease, vasculitis, Sjögren’s disease, and leukocytoclastic vasculitis) had a significantly higher prevalence in the JIA cohort compared with the general paediatric population [34].

Studies indicate that ADs occur much more frequently in relatives of JIA patients than in healthy controls. According to a study by van Straalen et al. [38], parents of patients with JIA were more likely to have several ADs, such as psoriasis, AITD, RA, and ankylosing spondylitis. Factors associated with a family history of AD in JIA included older age at JIA onset (p < 0.01), Scandinavian residence (p < 0.01), ERA, PsA and undifferentiated arthritis (p < 0.01), ANA positivity (p = 0.03), and HLA-B27 positivity (p < 0.01). However, the presence of AD in the family did not influence severity or the course of JIA [38]. In their observational study, Al-Mayouf et al. [39] noted that ADs cluster within families of patients with JIA with a high proportion of ERA and PsA. Furthermore, JIA patients with a family history of ADs had more disease damage [39]. In the previously mentioned study by Tronconi et al. [36], 76 families were analysed, with a total of 438 relatives. The prevalence of ADs was 13%, higher in first-degree relatives than in second-degree relatives. The most common disease was AITD, both in first- and second-degree relatives. There was no difference in the age of JIA onset between patients with positive and negative knowledge of AD (p > 0.05) [36].

Autoimmune thyroid diseases include HD, which results mostly in hypothyroidism, and GD, which causes hyperthyroidism. If left untreated, hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism can result in a variety of symptoms, thereby affecting the child’s development and functioning. It is estimated that the prevalence of AITD in JIA ranges from 1 to 44% [38]. Due to the incomplete understanding of the correlation between JIA and AITD, there is currently no indication for screening for AITD in JIA patients [38, 40]. Individuals with JIA are more likely to develop antithyroid antibodies, especially if they have a family history of thyroid dysfunction [33]. In their observational cross-sectional study, Sapountzi et al. [41] examined 130 patients with JIA and found that the prevalence of autoimmune thyroiditis was higher compared to the general population. Most patients (70%) had a family history of at least one AD and 30.8% of HT. More than half had ERA, 22.3% had oligoarthritis, and 15.4% had PsA. Thyroid autoantibodies were detected in 16.9% of patients. Most patients were euthyroid (normal TSH and free thyroxine [fT4]), whereas 13.6% had overt hypothyroidism determined by elevated levels of TSH, decreased levels of fT4, and typical ultrasound findings for HT. The prevalence of clinical cases of HT was 2.3% [41]. In another study, van Straalen et al. [38] reported that family history of AITD, female gender, positive ANA test result, and older age at JIA development were independent predictors of AITD. Family history of AITD was found to be the most important predictor of AITD in JIA. Therefore, it is a crucial factor for clinicians to consider when estimating the risk of developing AITD in patients with JIA [38]. Valenzise et al. [33] examined 51 patients with JIA, with a mean age of 9.9 ±3.94. A family history of AD was found in 21.6% of patients. The majority of patients (68.6%) had oligoarthritis, 27.5% polyarthritis, 2% had systemic onset, and another 2% had undifferentiated arthritis. Among the patients, 17.4% had TSH > 4.2 μU/l, 12.5% had TSH > 10 μU/l and were classified as hypothyroidism, and 87.5% had TSH between 4.2 and 10 μU/l with a normal fT4, which was classified as isolated hyperthyrotropinaemia. Of the patients, 6.4% were receiving levothyroxine therapy. All patients were diagnosed with AITD at the time of JIA. All patients treated for AITD had abnormal echographic findings. Among the patients, 7.8% had positive anti-TPO antibodies, and 3.9% had positive anti-TG antibodies. After a thorough analysis of the results in the individual subtypes of JIA, Valenzise et al. [33] concluded that although oligoarthritis is the most common, thyroid dysfunction occurred more frequently in patients with polyarthritis. The polyarticular subtype showed a higher presence of anti-TPO antibodies (21.4%) with a significant difference compared with the oligoarticular subtype (2.9%). In the group with polyarthritis, 7.1% of patients had positive anti-TG antibodies, whereas in the group with oligoarthritis, the frequency was 2.9%. In the polyarticular subtype, there was a significant frequency of a family history of AD (57.1%), while in the oligoarticular subtype group it was only 8.6%. The results of this study suggest that special attention should be paid to the diagnosis of thyroid abnormalities in patients with polyarthritis [33]. In their study, Revenco et al. [42] found no cases of overt clinical and biochemical hypothyroidism among 97 children with JIA. In contrast, mean levels of free triiodothyronine (fT3) were elevated in 36.4% and fT4 in 29.7% of patients. Anti-TPO antibodies were detected in 5 of 97 patients (5.15%), and anti-TG antibodies in 2 patients (2.06%). All patients with positive antithyroid antibodies were female. Ultrasonographic examination of the thyroid revealed abnormalities in 41% of cases; most of them were cystic and hypoechoic. In patients with thyroid nodules on ultrasound, thyroid scintigraphy did not show pathological activity or other processes. However, 2 patients had a mean thyroid volume above 2 standard deviations (SDs) of the mean according to the reference values for their age. Increased vascular flow in thyroid Doppler examination was found in 26% of patients. Correlation and regression analysis showed that low age at JIA diagnosis and longer disease duration are predictive factors for these thyroid disorders [42]. Alhomaidah et al. [43] highlighted the more frequent co-occurrence of endocrinopathies in children diagnosed with JIA and SLE. They examined a total of 42 patients, 22 with JIA and 20 with SLE. Fifteen patients (35.7%) had a family history of ADs. The most frequently detected endocrinopathies were vitamin D deficiency (35%) and thyroid disease (31%). Eight patients with JIA and seven with SLE had low vitamin D levels; hyperparathyroidism was detected in 10 patients. Thyroid dysfunction was observed in 13 patients (8 with SLE, 5 with JIA), and 2 patients were euthyroid with positive thyroid autoantibodies. In addition, 7 patients had subclinical hypothyroidism (high TSH, normal fT4), and 4 patients had overt hypothyroidism (high TSH, low fT4). Seven patients (4 with SLE and 3 with JIA) had short stature due to growth hormone (GH) deficiency (low insulin-like growth factor-1 [IGF-1] and insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3 [IGFBP-3]). Two patients had delayed puberty associated with low luteinizing hormone (LH) levels. Diabetes mellitus was more frequently observed in patients with JIA (4 patients) than in patients with SLE (1 patient) [43]. In their retrospective study, Torres-Fernandez et al. [44] examined a total of 193 patients with JIA, of whom 64% were female and the median age at disease onset was 5.6 years. The three most common ILAR categories were oligoarthritis (53%), RF-negative polyarthritis (20%), and ERA (10%). Hyperthyrotropinaemia was found in 14 (9%) children, 10/14 were female (71%). Only 1 patient (0.6%), a girl with ANA negative oligoarthritis and normal immunoglobulin A (IgA) serum levels, was positive for anti-TG and anti-TPO antibodies, and required pharmacological replacement therapy. All the other children had transient hyperthyrotropinaemia [44].

In the initial workup and ongoing evaluation of patients with JIA, clinicians should consider the presence of other potential ADs, which may develop earlier in this patient group than in the general paediatric population [34, 35]. It has been demonstrated that familial ADs are a risk factor for the development of JIA; thus it is imperative to consider certain diseases in the family history during the diagnostic stage [36, 45]. Due to the importance of thyroid hormones in proper child development, it is necessary to better understand the correlation between JIA and AITD, particularly HT, and identify risk factors for the onset of these diseases [38]. Autoimmune thyroid tests should be considered as part of the diagnostics in patients with JIA [41].

Growth retardation

Disturbance in the proper development and growth of children is one of the possible symptoms of JIA.

Depending on the subtype of JIA, patients experience growth retardation with varying frequency. It affects 10.4% of patients with the polyarticular subtype, compared with up to 41% of patients with the more severe subtype of the condition, systemic-onset JIA. Untreated patients experience a loss of up to 3 SDS for height in prepubertal years [46].

It is currently assumed that the marked inflammation and catabolic state are at least partially responsible for impeding growth development, marking the importance of quick and proper treatment as the best measure to secure proper development by the patient [47]. The prime pro-inflammatory cytokines associated with this process are interleukin-6 (believed to have a systemic effect on the GH–IGF-1 axis), interleukin-1β, and tumour necrosis factor α, which have an adverse effect locally on the growth plate chondrocyte dynamics, affecting longitudinal bone growth [48, 49].

The catabolic state JIA patients often find themselves in is also referred to as “rheumatoid cachexia,” leading to hepatic GH resistance, causing elevated systemic GH levels as well as fibroblast growth factor-21 (FGF-21) activation, which prohibits the binding of GH receptors of the chondrocytes present in the growth plate [49].

The proper development of the patient to allow them the best possible quality of life through childhood and adulthood is one of the primary goals of treatment. As such, proper treatment and subsequent adjustment of it are important to allow the child to reach the optimum height. Patients tend to experience an onset of growth retardation at the beginning of the disease with a possible “catch-up” phase in growth speed once the condition is properly managed [46].

The likelihood of growth impairment in JIA varies according to its subtype.

Systemic-onset JIA is characterised by systemic symptoms such as fever, characteristic rash, lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly or serositis. In this variant, growth retardation can be a symptom.

Oligoarticular JIA is noted to rarely occur with growth retardation, although this form tends to display localised excessive bone growth, leading to asymmetric limb length. This can be prevented with early appropriate general treatment and intra-articular GC injections [46].

Polyarticular JIA, which is arthritis of multiple joints (5 or more) during the first 6 months of the disease onset, tends to present with mild growth retardation.

Alternatively, paediatric patients may suffer from insufficient growth due to GC therapy administered to handle the primary disease. This problem was severely reduced in patients receiving cytokine antagonist (biological) treatment. Glucocorticosteroid therapy inhibits growth by reducing GH secretion and minimising IGF-1 activity through decreased expression of receptors for the protein in the targeted tissue [46]. Therefore, it is important to regularly measure a patient’s growth and plot it to ensure they are following their age-appropriate growth trajectory. Furthermore, proper nutrition and supplementation of vitamin D and calcium should be part of a systemic approach to handling the condition. A patient’s development in these areas should be assessed every 3 months [50]. Additionally, it is possible to administer concurrent GH therapy allowing JIA patients to have a normal growth experience and puberty development. Patients receiving GH therapy 12–15 months after receiving GC therapy had gained height of +0.37 ±1.5 SD and continued to grow in their appropriate growth trajectory, while untreated children experienced a loss of height of 0.96 ±1.2 SD. This improvement has been confirmed in long-term studies [46].

Bisphosphonate therapy has been shown to increase bone mineral density in children with JIA. However, there are concerns that it may impair bone remodelling and healing [47].

Hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis

The adrenal glands consist of a cortex and a medulla [51–53]. The cortex is divided into three layers: the zona glomerulosa, zona fasciculata, and zona reticularis. The zona glomerulosa synthesizes and secretes mineralocorticosteroids (mainly aldosterone), the zona fasciculata GCs (mainly cortisol), and the zona reticularis androgens (mainly androstenedione) [52, 53]. The secretion of mineralocorticosteroids is regulated independently of the hypothalamus and pituitary gland, through the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system [51–54]. However, the secretion of cortisol and androgens is regulated by the HPA axis via corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), and GC and mineralocorticosteroid receptors [51–55]. When the level of GCs in the blood is low, the hypothalamus is stimulated to secrete CRH, which then stimulates the pituitary gland to release ACTH. Adrenocorticotropic hormone then stimulates the zona fasciculata to secrete and synthesize cortisol, leading to an increase in its blood concentration [13]. In the case where the level of GCs in the blood is high, the secretion of CRH in the hypothalamus is inhibited, followed by inhibition of ACTH secretion in the pituitary gland, and subsequently, inhibition of GC secretion by the adrenal glands [56]. This mechanism is known as negative feedback.

Adrenal insufficiency

Mineralocorticosteroids and GCs are essential for the proper functioning of the body [51]. Mineralocorticosteroids regulate sodium-potassium balance, while GCs regulate carbohydrate metabolism. Adrenal insufficiency is defined as a condition in which the adrenal cortex is unable to synthesize GCs and/or mineralocorticosteroids [51, 53]. Adrenal insufficiency is categorized into primary (related to the adrenal glands), secondary (related to the pituitary gland and ACTH), and tertiary (related to the hypothalamus and CRH) [51, 53]. Adrenal insufficiency can present in a non-specific and difficult-to-diagnose manner [52, 57]. Nevertheless, it often manifests as psychiatric disturbances, anorexia, vomiting, weight loss, fatigue, and recurring abdominal pain [54].

The commonest cause of primary adrenal insufficiency is autoimmune damage to the adrenal cortex (Addison’s disease), while in children it is congenital adrenal hypertrophy [54]. However, the most frequent cause of adrenal insufficiency is the use of exogenous GCs, resulting in tertiary hypofunction [51, 53]. Adrenal insufficiency caused by GCs is a well-known side effect of therapy with these medications and is expected in patients taking GCs in doses equivalent to more than 5 mg of prednisone for at least 3 weeks [53].

To diagnose adrenal insufficiency, it is necessary to conduct tests for ACTH levels, cortisol levels, plasma renin activity, aldosterone, and a chemical panel [54]. Additionally, an ACTH stimulation test may be performed to differentiate the causes of the insufficiency [54, 57]. Individuals with secondary or tertiary adrenal insufficiency typically have preserved mineralocorticosteroid function [51]. Additionally, cortisol deficiency is characterized by hypoglycaemia, while aldosterone deficiency is associated with hyperkalaemia and hyponatraemia [52, 54].

According to a systematic review and meta-analysis of 73 studies, the median prevalence of adrenal insufficiency due to GC use was 37% among patients receiving any form of these medications [53]. Additionally, a meta-analysis of 74 studies showed that the prevalence of secondary adrenal insufficiency caused by intra-articular GC treatment can be as high as 52.2% [58]. It is worth noting the case of a 4-year-old girl with polyarticular JIA, who was treated with intra-articular injections of triamcinolone hexacetonide (with individual doses ranging from 0.5 mg to 20 mg) or dexamethasone (with individual doses of 1.5 mg) [59]. In total, patient received 46 individual injections of these substances, which were administered to all affected joints. This resulted in a cumulative dose equivalent to 250 mg of prednisolone (with triamcinolone 1 mg = prednisolone 1.25 mg, 75% triamcinolone content in triamcinolone hexacetonide; dexamethasone 1 mg = 6.25 mg prednisolone). A few weeks after this treatment, patient was hospitalized due to a deteriorating health condition. This child was diagnosed with a severe urinary tract infection and iatrogenic CS with adrenal insufficiency, which was linked to the previously administered GC injections.

Conclusions

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis is among the important interdisciplinary problems in paediatrics. To maintain the best possible well-being of the patient, a thorough medical history of the patient and family is essential. The patient should remain under the constant, regular supervision of a specialist. The clinician must be knowledgeable regarding the planning of extensive prophylaxis and diagnosis of comorbid disorders, and if they occur, adjust the treatment plan to the underlying condition with care.