Introduction

Familial Mediterranean fever (FMF) is the most common hereditary monogenic auto-inflammatory recurrent fever. It mainly affects ethnic groups in the Middle East and around the Mediterranean [1].

Familial Mediterranean fever is the prototypical inherited autoinflammatory disease. The mutations occur in the Mediterranean fever gene MEFV that encodes the pyrin protein [2]. Pyrin controls the activation of caspase-1, leading to interleukin (IL)-1β production. Additionally, pyrin regulates the transcriptional nuclear factor κ-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB), which in turn stimulates the production of other proinflammatory cytokines [3]. In physiological conditions, this protein inhibits inflammasome activity and helps in the downregulation of the innate immune response [2]. Therefore, mutations in the MEFV gene lead to disruption of the innate immune system. This abnormality occurs mainly in monocytes and neutrophils, and results in the abnormal secretion of certain pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-6, IL-18, and tumor necrosis factor [4]. This cytokine secretion leads to a non-specific increase in the proteins of the acute phase of inflammation (C-reactive protein [CRP], serum amyloid A protein [SAA], fibrinogen, etc.) and is responsible for the clinical signs of systemic inflammation (fever, muscle pain, and inflammation of serous membranes). Familial Mediterranean fever begins before the age of 20 in approximately 90% of patients. In more than half of them, the disease appears within the first 10 years of life.

The major long-term complication of FMF is amyloid A amyloidosis (AA amyloidosis). It mostly affects the kidneys and gastrointestinal tract, but it can also affect the liver, spleen, heart, and thyroid. It is a severe, life-threatening complication with a poor prognosis [5].

Treatment mainly aims to prevent disease outbreaks and reduce inflammation to prevent complications such as amyloidosis. First-line treatment has been based on colchicine since the 1970s with proven effectiveness in preventing and treating amyloidosis as well as managing acute FMF attacks [5]. However, 5 to 15% of patients with FMF are resistant and/or intolerant to colchicine and must be given alternative treatment options [6].

Recently, biological therapies, notably IL-1 antibody (anti-IL-1) medications including anakinra, canakinumab, and rilonacept, have been proven to be effective and safe in managing recurrent episodes and persistent inflammation among FMF patients. These treatments selectively target immune system components such as IL-1 to regulate the inflammatory cascade and mitigate disease severity [2, 5, 7–10].

Although anti-IL-1 medications are biological first-line treatment alternatives for FMF patients with colchicine resistance or intolerance [2], they may not yield sufficient efficacy, particularly in amyloidosis, or may be contraindicated due to adverse events [11, 12]. In this particular case, anti-IL-6 inhibitors have been suggested to be potentially beneficial [13].

Tocilizumab (TCZ), a humanized monoclonal antibody that blocks the action of IL-6 receptors, has been approved for the treatment of many autoimmune/inflammatory diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis [14], giant cell arteritis [15], and cytokine release syndrome [16], with acceptable safety and effectiveness. Numerous studies have revealed encouraging outcomes in managing FMF attacks and amyloidosis using TCZ.

While many reviews assessing the efficacy and safety of drugs are available [17], notably the effectiveness and safety anti-IL-1 drugs in FMF [2], systematic reviews analyzing the available evidence of anti-IL-6 drugs regarding the effectiveness and safety in FMF are lacking.

This systematic literature review aimed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of TCZ in the treatment of FMF.

Material and methods

Data sources and strategy search

The present systematic literature review was conducted according to the updated Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [18]. Two authors (S.O., B.S.) independently performed the search using the PICO (Patient, Intervention/Exposure, Comparison, Outcome) strategy. The following online databases were searched: PubMed, Embase, Scopus, Web of Science, and the Cochrane Library, for literature published until February 2024. Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) used were: “Tocilizumab” OR “Interleukin-6 inhibitor” AND “Familial Mediterranean Fever”. Manual research was also performed by reviewing the references of the retained articles.

Study selection

Eligible articles were clinical trials, cohort studies, cross-sectional studies, case series, and case reports including adult patients (≥ 18 years) with FMF treated by TCZ. The selected languages were English and French.

The same two authors (SO, BS) independently screened all the articles generated, according to title, abstract, and full text. Redundant articles were removed, and those that did not satisfy the eligibility criteria were excluded. Selection discrepancies were resolved through discussion and consensus. All authors agreed on the final decision of the studies to be included.

Data extraction

A standardized data collection form was used, and the following information was collected:

study characteristics: design of the study, country, year, number of patients,

population characteristics: age, sex,

data related to FMF characteristics: duration, organ involvement,

data related to TCZ treatment: dose, administration schedule, duration, associated treatments,

data related to the efficacy of TCZ: clinical and laboratory data,

data related to the safety of TCZ: short-term and long-term side effects were assessed.

Study quality assessment

Each included article was critically appraised for methodological quality using the Cochrane Risk of Bias 2 (RoB 2) tool for randomized clinical trials (RCTs) [19] and the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale for non-RCTs and observational studies [20]. One author (BS) appraised the quality of eligible studies.

Results

Retrieved articles

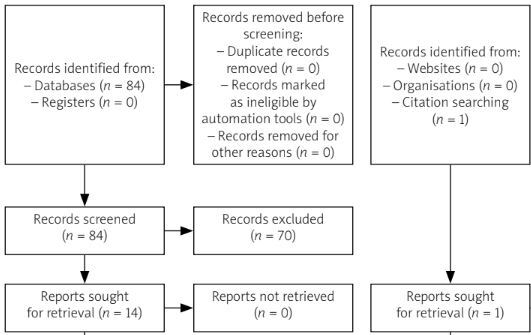

The systematic search identified initially 84 potentially eligible publications. Then, 60 studies were excluded based on title screening (primary exclusion) and a further 10 studies were excluded after abstract screening (secondary exclusion). Four duplicates were removed and one study was added through hand research.

Finally, we included a total of 11 eligible studies in our systematic review [21–31]. The PRISMA flow diagram for the review selection process is shown in Figure 1.

Studies and population characteristics

Of the collective 11 studies, 6 were case reports [21, 23, 24, 26, 28, 30], 3 were case series [22, 29, 31] and 2 were RCTs [25, 27]. The studies were conducted in Japan (6) [21, 23, 24, 26, 27, 30], Turkey (3) [22, 29, 31], Germany (1) [25] and Greece (1) [28]. The total number of participants receiving TCZ was 68 patients. Studies and population characteristics are summarized in Table I.

Table I

Characteristics of studies and population

| First author/Year [Ref.] | Country | Study design | Number of patient | Sex/sex ratio | Age/mean age ±SD/Median (min.–max.) [years] | Disease duration/mean duration ±SD/Median (min.–max.) [years] | Heterozygous MEFV mutation [n (%)] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aikawa et al. 2016 [20] | Japan | Case report | 1 | M | 53 | 16 | Genetic analysis was not mentioned |

| Colak et al. 2019 [21] | Turkey | Case series | 15 | 3/12 | 42.07 ±14.37 | 25.73 ±10.86 | 11 (73.3) |

| Fujikawa et al. 2013 [23] | Japan | Case report | 1 | F | 19 | 12 | 1 |

| Hamanoue et al. 2016 [24] | Japan | Case report | 1 | M | 51 | 21 | 1 |

| Henes et al. 2022 [25] | Germany | RCT | 13 TCZ 12 placebo | 6/7 TCZ 5/7 placebo | 33 (18–53) TCZ 28.5 (18–41) placebo | 18 (2–44) TCZ 12.5 (0–29) placebo | 8 (61.5) TCZ 5 (41.6) placebo |

| Inui et al. 2020 [26] | Japan | Case report | 1 | M | 51 | NR | 1 |

| Koga et al. 2022 [27] | Japan | RCT | 11 TCZ 12 placebo | 3/11 TCZ 6/6 placebo | 37.5 (14.5) TCZ 45.9 (11.0) | NR | 6 (86) TCZ 9 (75) placebo |

| Serelis et al. 2015 [28] | Greece | Case report | 1 | F | 32 | 32 | The type of mutation was not specified |

| Ugurlu et al. 2017 [29] | Turkey | Case series | 12 | 6/6 | 35.2 ±10 | 6.43 ±6.90 | 8 (66.6) |

| Umeda et al. 2015 [30] | Japan | Case report | 1 | F | 64 | NR | 1 |

| Yilmaz et al. 2014 [22] | Turkey | Case series | 11 | 1/10 | 37.9 (22–76) | NR | 3 (27.2) |

Tocilizumab indications

Tocilizumab has been used in FMF for different indications (Table II). First, TCZ was introduced for treating AA amyloidosis in 7 studies [21, 22, 24, 26, 28, 29, 31]. In these studies, amyloidosis was confirmed by histopathological findings of biopsies mostly from renal and/or gastrointestinal origins. The second most frequent indication was for an active disease with disease activity defined by the occurrence of at least one fever attack in 3 months (2 studies) [25, 27]. In one study, TCZ was initiated to treat a resistant case of myositis [30]. Finally, in the study of Fujikawa et al. [23], it was introduced to treat a case of erysipelas-like erythema associated with periodic fever and polyarthralgia that was mistaken for adult-onset Still disease.

Table II

Indications of tocilizumab, doses, concomitant and previous treatment

| First author | Number of patients | Indication for treatment by TCZ | Dose | Number of infusions/injections mean ±SD/Median (min.-max.) | Follow-up (months) | Co-medication | Previous DMARDS/biologics before TCZ (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aikawa et al. [20] | 1 | Gastrointestinal amyloidosis | 162 mg every 2 weeks | NR | 13 | Colchicine | None |

| Colak et al. [21] | 15 | Amyloidosis | 8 mg/kg bw monthly | 12 (3–96) perfusions | 12 | Colchicine | None |

| Fujikawa et al. [23] | 1 | FMF attack with fever synovitis and erysipelas like erythema | 8 mg/kg bw monthly | NR | NR | None | Methotrexate (n = 1) |

| Hamanoue et al. [24] | 1 | Gastrointestinal and renal amyloidosis | 8 mg/kg bw monthly | NR | 24 | None | Etanercept (n = 1) |

| Henes et al. [25] | 13 | Active disease | 8 mg/kg bw monthly | 4 perfusions | 4 | Colchicine NSAIDS GC | Anakinra (n = 1) Canakinumab (n = 1) |

| Inui et al. [26] | 1 | Renal amyloidosis | 8 mg/kg bw monthly | NR | 108 | NR | None |

| Koga et al. [27] | 11 | Active disease | 162 mg weekly | NR | 6 | Colchicine GC | NR |

| Serelis et al. [28] | 1 | Renal amyloidosis | 8 mg/kg bw monthly | NR | 48 | Colchicine | None |

| Ugurlu et al. [29] | 12 | Amyloidosis | 8 mg/kg bw monthly | 15.3 ±12.1 perfusions | 17.5 ±14.7 | Colchicine | Anakinra (n = 5) Canakinumab (n = 3) Infliximab (n = 3) Cyclophosphamide (n = 2) Etanercept (n = 1) Sulfasalazine (n = 2) Azathioprine (n = 1) |

| Umeda et al. [30] | 1 | Active disease with myositis | 8 mg/kg monthly | NR | 9 | Colchicine | None |

| Yilmaz et al. [22] | 11 | Renal amyloidosis | 8 mg/kg monthly | 9 perfusions | NR | Colchicine | None |

In 10 studies, TCZ was introduced as patients showed resistance or intolerance to colchicine used at the maximum tolerated dose (1.5–2 mg/day) [21, 22, 24–31], whereas, in the Fujikawa et al. [23] study, it was resistance to methotrexate associated with prednisolone (1 mg/kg/day) that led to its use.

Notably, several patients experienced intolerance or resistance to synthetic disease-modifying drugs or biologics before receiving TCZ whether these treatments were indicated for treating FMF or another associated disease. These previous treatments included methotrexate (1 patient) [23], azathioprine (1 patient) [29], sulfasalazine (2 patients) [29], cyclophosphamide (2 patients) [29], anakinra (6 patients) [25, 29], canakinumab (4 patients) [29], infliximab (3 patients) [29] or etanercept (2 patient) [24, 29].

Route of administration

In 9 studies corresponding to 56 patients (82%), TCZ was administered intravenously every 4 weeks at a dose of 8 mg/kg [22–26, 28–31]. The subcutaneous route was used for 2 studies, at the dose of 162 mg every week [27] and 162 mg every 2 weeks [21] (Table II).

Concomitant treatment

In 8 studies among 11 corresponding to 62 patients (91%), patients were receiving a co-medication with colchicine [21, 22, 25, 27–31]. In the studies of Henes et al. [25] and Koga et al. [27], patients were also allowed to take a low dose of glucocorticosteroids (≤ 10 mg/day and ≤ 5 mg/day respectively) as long as these doses were stable throughout the studies. Particularly, in the study of Henes, non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs that were allowed as a rescue treatment for attacks were used by 61.5% of patients [25].

Efficacy data

Familial Mediterranean fever attacks

The effect of TCZ on FMF attacks was recorded in 10 studies, corresponding to 57 patients (84%) [21–26, 28–31].

Tocilizumab showed efficacy in controlling fever (4 studies [21, 23, 24, 30]) abdominal pain (3 studies [22, 24, 26]) arthritis or arthralgia (5 studies [21, 23, 24, 26, 28]) myalgia or myositis (2 studies [22, 30]), erysipelas-like erythema (1 study [23]), chest pain (1 study [22]) and headache (1 study [22]).

Two studies focused on evaluating the efficacy of TCZ in reducing the frequency of attacks [27, 28]. Although the study of Koga et al. [27] showed no efficacy vs. placebo at the primary endpoint (24 weeks), attack recurrence was significantly lower in the TCZ group (hazard ratio = 0.457; 95% CI: 0.240–0.869) [27]. Additionally, it reported a tendency for fewer attacks in the long term (48 weeks) [27].

Inflammatory markers

Tocilizumab showed efficacy in controlling inflammatory markers. All 6 studies [24–27, 29, 30] reporting CRP variation under TCZ noted a decrease in levels, with 4 studies showing a fall to a normal range [24, 25, 27, 30] (Table III). Additionally, the study of Ugurlu et al. [29] that recorded erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) variation noted a decrease from 48.7 ±3 mm/h to 27.3 ±mm/h.

Table III

Efficacy data of tocilizumab

| First author | Number of patients | Response to TCZ (n) | Number of attacks under TCZ (n)/Median (min.-max.) | CRP [mg/dl] | Renal function | Proteinuria | SAA | Amyloid deposits |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aikawa et al. [20] | 1 | 1: no attacks | 0 | NR | NR | – | NR | Disappeared |

| Colak et al. [21] | 15 | 8: no attacks 6: decreased attacks Frequency 1: no response | 0 (0–10) | – | – | – | – | NR |

| Fujikawa et al. [23] | 1 | 1: no attacks | 0 | NR | – | – | – | – |

| Hamanoue et al. [24] | 1 | 1: no attacks | 0 | Decreased to 0.0 | Creatinine decreased to 1.6 mg/dl | Decreased to 0.3 mg/day | Decreased to 5.0 μg/ml | Marked reduction of amyloid deposits |

| Henes et al. [25] | 13 | 2: responders 11: no response (primary endpoint: PGA score of < 2 and normalization of SAA and CRP and/or ESR) | NR | CRP < 0.5 for 69.2% of patients (p < 0.011) | – | – | SAA < ULN (10 mg/l) in 7 patients (53.8%) (p < 0.015) | NR |

| Inui et al. [26] | 1 | 1: no attacks | NR | Decreased | Creatinine: increased from 1.9 to 2.3 mg/dl GFR: decreased from 31.1 to 24.1 ml/min | Decreased from 3.8 g/day to 1.4 g/day | – | Decrease of up to 19% |

| Koga et al. [27] | 11 | NR | 11: TCZ 20: placebo (p = 0.58) Recurrence of attacks significantly lower with TCZ (HR = 0.457; 95% CI: 0.240–0.869) | Median CRP decreased from 0.70 (0.20–82) to 0.2 (0.20–0.80) | - | - | Median SAA decreased from 7.5 mg/l (2.5–1,100 mg/l) to 2.7 mg/l (2.5–41 mg/l) in TCZ group | - |

| Serelis et al. [28] | 1 | 1: decreased attacks frequency | 2 milder attacks/year | NR | Creatinine decreased from 2 to 1.2 mg/dl | Decreased from 9 g/day to 3.6 g/day | – | NR |

| Ugurlu et al. [29] | 12 | 10: no attacks 1: less frequent and mild attacks 1: no response | NR | Mean CRP decreased from 18.1 ±19.5 to 5.8 ±7.1 | Stable Mean creatinine: from 1.1 ±0.9 to 1.0 ±0.6 mg/dl mean GFR from 111.7 ±50.1 to 108.9 ±54.8 ml/min | Decreased from 6,537.6 ±6,526.0 mg/day to 4,745.5 ±5,462.7 mg/day (in 10 patients) | – | NR |

| Umeda et al. [30] | 1 | 1: no attacks | 0 | Suppressed to the normal range | – | – | – | – |

| Yilmaz et al. [22] | 11 | 10: no attacks 1: no response | NR | NR | Creatinine: Increased (n = 1) Stable/slightly increased (n = 10) | Decreased (n = 7) Stable (n = 2) Increased (n = 2) | – | NR |

Tocilizumab was also found to be efficient in controlling the levels of SAA [24, 25, 27] (Table III).

Renal function

Renal function in patients on TCZ was assessed in 5 studies, corresponding to 26 patients [24, 26, 28, 29, 31]. The effect of TCZ on renal function was inconsistent. A decrease in serum creatinine levels was reported by Hamanoue et al. [24] and Serelis et al. [28], while Inui et al. [26] observed an increase in its level. Conversely, the studies of Ugurlu et al. [29] and Yilmaz et al. [31] observed stabilization of serum creatinine levels in most patients.

Proteinuria

Urinary protein excretion in patients on TCZ was assessed in 5 studies, corresponding to 26 patients [24, 26, 28, 29, 31]. Overall, a decrease in proteinuria levels was reported in 20 patients (77%) (Table III). For instance, in their study, Yilmaz et al. [31] reported a decrease or normalization of 24-hour proteinuria in 7/11 patients. A reduction of 24-hour proteinuria was also observed in 10/12 patients in the Ugurlu et al. study [29].

Amyloidosis

Although 7 studies were conducted in patients with histologically proven AA amyloidosis corresponding to 43 patients [21, 22, 24, 26, 28, 29, 31], only 3 studies, corresponding to 3 patients, reported the effect of TCZ on amyloid deposition [21, 24, 26]. Interestingly, a reduction of amyloid deposition was confirmed in all 3 cases. This reduction was variable: from a 19% reduction [26] to a complete resolution [29].

Efficacy data in patients with resistance to anti-interleukin-1 biologics

Tocilizumab was used in 8 patients with known resistance to anti-IL-1 biologics.

Data were only available for the Ugurlu et al. study [29], corresponding to 6 patients, among whom 2 had had 2 anti-IL-1 biologics: anakinra and canakinumab. Tocilizumab administration was associated with a decrease in creatinine levels in 1 patient, stabilization in 3 patients, and an increase in 2 patients. Accordingly, glomerular filtration increased in 3 patients and decreased in 3 patients. Efficacy data on proteinuria were also inconsistent, as 4 patients experienced a decrease in their proteinuria levels, while 2 patients showed an increase.

Tolerance data

Tocilizumab tolerance data were reported in 5 studies, corresponding to 62 patients (91%) [22, 25, 27, 29, 31]. Overall, adverse events were recorded in 19 patients (30%; Table IV). Three serious adverse events were noted in 3 patients (13%) including ileitis, myocarditis, and headache [25, 27].

Table IV

Tolerance data of tocilizumab

| First author | Number of patients | Serious adverse events (n) | Infections (n) | Liver enzymes alteration (n) | Blood count parameters abnormalities (n) | Infusion reaction/injection site reaction (n) | Other adverse events (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aikawa et al. 2016 [20] | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Colak et al. 2019 [27] | 15 | None | None | None | None | None | None |

| Fujikawa et al. 2013 [21] | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Hamanoue et al. 2016 [17] | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Henes et al. 2022 [1] | 13 | 1: ileitis | None | 1: increased liver enzymes: | NR | NR | NR |

| Inui et al. 2020 [26] | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Koga et al. 2022 [24] | 11 | 2 (1: myocarditis 1: headache) | NR | NR | NR | 2: injection site reactions | 10 (8: hypofibrino-genemia 2: headache) |

| Serelis et al. 2015 [19] | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Ugurlu et al. 2017 [22] | 12 | NR | 1: non-complicated urinary tract infection 1: respiratory tract infection | None | None | None | 1: transient diplopia 1: increased blood pressure |

| Umeda et al. 2015 [25] | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Yilmaz et al. 2014 [23] | 11 | None | NR | 1: increased liver enzymes | 1: thrombo-cytopenia | NR | NR |

Interestingly, no serious or opportunistic infections were reported. Among adverse events of special interest, 2 cases of increased liver enzymes and a case of mild thrombocytopenia were noted [25, 31]. Infusion reactions were not observed. However, 2 patients presented an injection site reaction [27]. Notably, the study of Koga et al. [27] found no difference between patients and placebo in the number and severity of adverse events.

Adverse events led to TCZ discontinuation in 5 patients [25, 27, 29]. No deaths associated with anti-IL-6 treatment were documented in 4 studies that reported death occurrence, corresponding to 50 patients [22, 25, 27, 31].

The follow-up period was mentioned in 9 studies among 11, corresponding to 56 patients [21, 22, 24–30]. It varied between 4 and 108 months, with a median of 13 months.

Discussion

In this systematic literature review, we assessed the efficacy and safety of TCZ in the management of FMF patients. This is the first systematic review to synthesize the available evidence about anti-IL-6 in FMF. Our results showed that TCZ is safe and effective for treating FMF, especially in terms of decreasing proteinuria and inflammatory markers. Three-quarters of the included patients experienced no FMF attacks or had a decreased frequency and/or severity of attacks under TCZ.

Familial Mediterranean fever attacks are usually associated with high levels of proteins of the acute phase of inflammation such as CRP. Our results showed that more than half of the patients had their CRP levels controlled and fell into the normal range. This seems to be directly linked to the physiopathological mechanism of action of IL-6 inhibitors. Interleukin-6 is a major pro-inflammatory cytokine known to prompt the liver to produce acute-phase proteins such as CRP. Therefore, by blocking the action of IL-6, anti-IL-6 inhibitors decrease CRP levels. This reduction in acute-phase proteins underscores the efficacy of anti-IL-6 treatment in modulating the immune response and mitigating inflammation in numerous otherinflammatory diseases [32].

Interestingly, SAA levels were also controlled in all patients on TCZ treatment. This holds major importance in FMF patients since, it may prevent organ amyloidosis.

In this systematic review, the effect of TCZ on amyloid deposition was reported in 3 patients out of 43 with histologically proven amyloidosis, and all 3 of them experienced a decrease in amyloid deposition.

Colchicine is the gold standard for the treatment of FMF [33]. Its efficacy has been proven to control the frequency and severity of recurrent attacks and also decrease the risk of amyloidosis complications [33]. Nonetheless, 5 to 15% of FMF patients exhibit resistance and/or intolerance to colchicine [9, 34]. Biological therapies, notably anti-IL-1, have been proven as alternative treatment options. Kilic et al. [2] suggested that combining colchicine with IL-1 inhibitors is preferred to mitigate subclinical inflammation. The effectiveness of anti-IL-1 treatment in reducing the frequency and severity of attacks as well as in managing secondary amyloidosis in FMF patients has been demonstrated in many observational studies [11, 35]. Nonetheless, there is presently no evidence demonstrating the efficacy of anti-IL-1 treatment in preventing the onset of AA amyloidosis in FMF patients [2]. Additionally, IL-1 inhibitors do have certain inconveniences. First, daily anti-IL-1 subcutaneous administration, particularly anakinra, could be associated with eventual injection-site reactions. Moreover, the administration of IL-1 inhibitors, particularly canakinumab, is associated with higher costs compared to TCZ treatment [22].

It is worth noting that IL-1 triggers the transcription of IL-6 and is associated with a marked rise in serum IL-6 levels observed in FMF patients [36]. Therefore, targeting IL-6 could be a promising alternative treatment in IL-1-mediated diseases such as FMF. In the same context, the efficacy of TCZ was demonstrated in systemic-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis, characterized by a distinct IL-1β signature [37].

Interestingly, our findings highlight promising results of IL-6 inhibitors in reducing amyloid deposition. However, the evidence supporting the efficacy of anti-IL-6 inhibitors in preventing or managing AA amyloidosis in FMF patients remains limited and requires further robust studies.

Proteinuria was controlled in most of our patients on TCZ. Conversely, data on renal function were inconsistent.

It is notable that we found heterogeneity in TCZ regimens. Most of the studies adopted monthly intravenous administration of an 8 mg/kg regimen of TCZ.

Additionally, 95% of patients in this review received simultaneously colchicine and TCZ. We agree with Klic et al. [2] that combined therapy of colchicine with IL-6 inhibitors could be more effective in controlling inflammation and disease activity.

Tocilizumab was indicated as a third line treatment in patients who experienced intolerance or resistance to synthetic disease-modifying drugs or biologics. Tocilizumab was prescribed to 8 patients who previously received IL-1 antagonists with no amelioration [29].

In our systematic review, TCZ was a safe treatment option within a median follow-up period of 13 months. Adverse events were reported in almost one-quarter of our patients, with only 3 cases with serious adverse events. Interestingly, no serious or opportunistic infections were reported. Adverse events led to TCZ discontinuation in 5 patients. No deaths associated with anti-IL-6 treatment were documented in our review.

Anti-IL-1 treatment is the preferred initial treatment option for colchicine-resistant FMF due to its effectiveness and approved status [25]. To the best of our knowledge, no studies have proven a direct comparison between anti-IL-1 and anti-IL-6 treatments in FMF patients. However, our results suggest that TCZ offers a safe and effective treatment option in FMF patients who are intolerant and/or resistant to colchicine and/or IL-1 blockers.

Study limitations

The limitations of this systematic review arise from its main reliance on case reports and small case series, resulting in missing data for several variables. Clinical trials with a long-term follow-up remain necessary to validate our findings and would further characterize the profile of efficacy and safety of TCZ in FMF patients.

Conclusions

Although the duration of follow-up of TCZ was short, our systematic literature review concluded that TCZ might present an acceptable profile regarding efficacy and safety in FMF adult patients, in reducing inflammatory markers, particularly CRP and SAA, and decreasing proteinuria. Data on renal function and amyloidosis need to be better clarified, but our data suggest that TCZ could be a good treatment option after IL-1 inhibitors. Further prospective studies or controlled clinical trials are necessary to establish definitive conclusions.