Introduction

Rheumatic diseases (RDs) encompass a range of chronic, inflammatory, and progressive disorders, including rheumatoid arthritis, spondyloarthropathies, Sjögren’s disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, scleroderma, and dermatomyositis. They can significantly impact patient health, frequently resulting in disability and a notable decline in quality of life [1]. In addition to their effects on individuals, these diseases impose a significant burden on healthcare systems and society in general [2, 3].

The application of artificial intelligence (AI) in healthcare, particularly for managing chronic medical conditions such as RDs, is an expanding area of research and development. Individuals with chronic illnesses frequently seek information and assistance to manage their afflictions, and AI-based tools, such as conversational agents and health coaching systems, are increasingly being created to address these needs [4, 5]. The integration of AI into the healthcare domain is progressing rapidly, with ChatGPT emerging as a prominent exemplar of this technological advancement. ChatGPT has gained widespread popularity among numerous users due to its capacity to generate detailed and rapid responses and its accessibility. As a large-scale language model, it employs deep learning techniques based on a variant of the transformer architecture to produce human-like responses to text-based input [6].

There is an increasing acknowledgment of the capacity of AI chatbots to provide prompt, precise, and empathetic information to individuals managing chronic health issues [7]. Nevertheless, the use of these tools in medical domains, particularly rheumatology, remains a largely unexplored area. Research has highlighted the strengths and weaknesses of these technologies, indicating that they can produce reasonably accurate and empathetic responses akin to those provided by medical professionals. The importance of ongoing management and patient education in rheumatology cannot be overstated. It is crucial to deliver information that is clear and easy to comprehend. Nonetheless, there is a valid concern that these chatbots might disseminate outdated or inaccurate information, underscoring the importance of a comprehensive evaluation of these emerging technologies [8, 9]. Indeed, the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology has acknowledged the potential of leveraging big data to tackle rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases. There is a strong emphasis on the necessity for further benchmarking studies to assess the effectiveness and reliability of AI-driven healthcare tools [10].

Considering all the background information provided, the objective of this study was to evaluate the quality, reliability, and readability of texts generated by ChatGPT on common RDs and compare the similarity and word count of these texts to the fact sheets created by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) to bridge the gap in the literature and provide insights for future studies. The ACR was selected due to its prominent international presence and active leadership in global rheumatology collaboration, which support its visibility and influence in standard-setting efforts [11].

Material and methods

This study was conducted at the İzzet Baysal Physical Treatment and Rehabilitation Training and Research Hospital from August 20, 2024 to September 15, 2024. The study adhered to the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines for cross-sectional studies to ensure transparent and standardized reporting [12].

Selection of diseases

Fifteen common RDs were identified from the fact sheets available on the official website of the ACR [13]:

rheumatoid arthritis,

systemic lupus erythematosus,

spondyloarthritis,

psoriatic arthritis,

fibromyalgia,

gout,

Sjögren’s disease,

osteoarthritis,

scleroderma,

polymyalgia rheumatica,

vasculitis,

inflammatory myopathies,

reactive arthritis,

familial Mediterranean fever,

Behçet’s disease.

Fact sheets that included comprehensive information on etiology, common signs and symptoms, treatment options, and lifestyle recommendations were retained for analysis. Those missing any of these key domains were excluded to maintain a standardized framework for comparison with the texts produced by ChatGPT.

Data collection

All browsing data were cleared entirely before initiating the searches, and a new account was created to engage with ChatGPT as a precautionary step to avoid any browsing history bias. Each RD query was handled on distinct chat pages to maintain clarity and enhance the efficiency of the analytical process.

Questions about common RDs were developed explicitly for this study based on the health information in the ACR fact sheets [13] to compare the readability, quality, and similarity of the ACR fact sheets and the texts generated by ChatGPT-4. The prompts submitted to ChatGPT were systematically developed based on the structural and thematic organization of the ACR fact sheets, incorporating key domains such as disease etiology, clinical features, treatment modalities, and lifestyle recommendations. A single, standardized prompt was used in English for each condition, and no iterative regeneration or manual optimization was performed. This methodological approach was intended to simulate typical, real-world patient interactions with AI-driven tools, in which users generally input straightforward, natural-language queries without applying advanced formatting or refinement techniques [14]. The study aimed to assess the model’s baseline performance in generating patient-facing health information under ecologically valid conditions by avoiding prompt manipulation. Prompt engineering strategies were deliberately excluded, as they represent a specialized skill set not widely adopted by the general public or typical end-users seeking medical information [15].

The following standardized questions were used in the study to evaluate the content related to common RDs:

“What is [disease]?”

“What are the signs/symptoms of [disease]?”

“What are common treatments for [disease]?”

“What are tips for living with [disease]?”

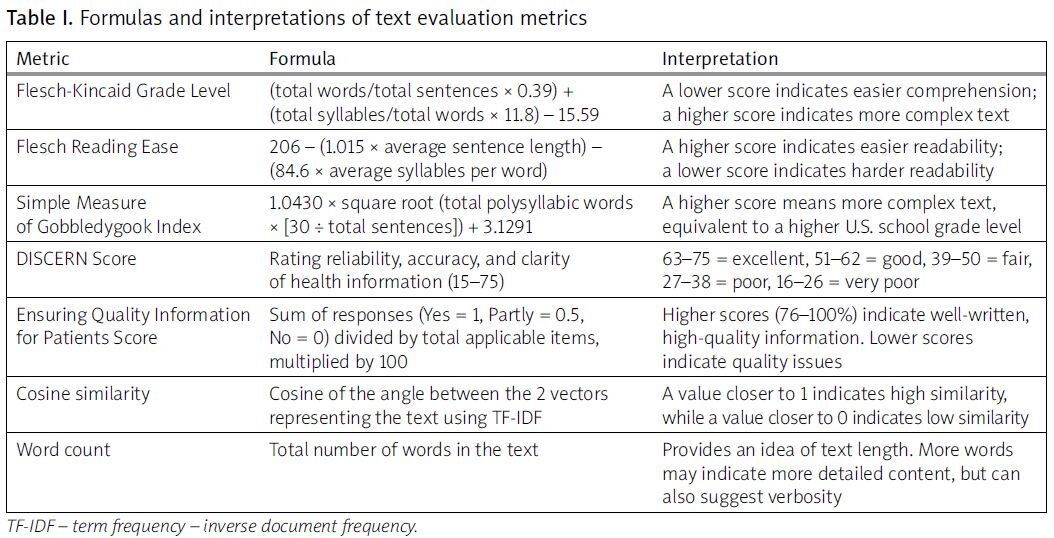

The obtained texts were then evaluated using established metrics. The meanings and interpretations of the text evaluation metrics, along with their formulas, are provided in Table I.

Table I

Formulas and interpretations of text evaluation metrics

Readability assessment

The Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level (FKGL), Flesch Reading Ease (FRE), and Simple Measure of Gobbledygook (SMOG) Index metrics were used to assess the readability of the content generated by AI chatbots. The FKGL is calculated by is calculated by multiplying the average sentence length (words per sentence) by 0.39, adding the average syllables per word multiplied by 11.8, and subtracting 15.59. A lower score signifies easier comprehension, while a higher one suggests greater linguistic complexity. The FRE measures document readability through calculations involving average sentence length multiplied by 1.015 and average number of syllables per word multiplied by 84.6; their difference is then subtracted from 206 [16]. The SMOG grade is calculated by multiplying 1.0430 by the square root of the total number of polysyllabic words multiplied by 30 divided by the total number of sentences, and then adding 3.1291 to the result. Finally, the result is rounded to the nearest whole number to determine the reading grade level. The score corresponds to a U.S. school grade level; a higher SMOG score indicates a more complex text [17].

Reliability and quality assessment

The DISCERN questionnaire, a validated tool developed to assist patients and information providers in evaluating the quality and reliability of the written content on treatment options, was used. The DISCERN tool is often used to assess the quality of health information based on criteria such as reliability, accuracy, and clarity. The minimum DISCERN score is 15; the maximum score is 75. DISCERN scores are categorized as follows: a score of 63 to 75 indicates excellent, a score of 51 to 62 is good, a score of 39 to 50 is fair, a score of 27 to 38 is poor, and a score of 16 to 26 is very poor [18].

The Ensuring Quality Information for Patients (EQIP) tool was used to analyze the quality of the gathered texts. This tool assesses different aspects of the material, including coherence and writing quality. The questionnaire consists of 20 inquiries, with response options including “yes”, “partly”, “no”, or “does not apply”. The scoring approach entails the multiplication of the quantity of “yes” responses by 1, “partly” responses by 0.5, and “no” responses by 0. The resultant values are aggregated, divided by the total quantity of items, and adjusted by removing the count of responses labeled as “does not apply”. Resources with scores ranging from 0 to 25% were categorized as “severe quality issues”, 26–50% as “serious quality issues”, 51–75% as “good quality with minor issues”, and 76–100% as “well written”, indicating exceptional quality [19].

Two independent raters (Y.E. and M.H.T.) evaluated all texts using the DISCERN and EQIP tools. Both raters jointly reviewed the assessment criteria before scoring to ensure consistency. All evaluations were performed independently and blinded to the text source (ChatGPT or ACR). In scoring discrepancies, a third reviewer (F.B.) acted as an arbitrator to resolve disagreements and determine the final rating.

Similarity and text length assessment

Cosine similarity, a well-established and widely used metric in text analysis, was employed to quantify the textual similarity between the materials. This metric measures the cosine of the angle between 2 numerical vectors, thereby providing a means to assess the similarity between textual elements [20]. Specifically, the scikit-learn library for Python was used, wherein the text was first transformed into a numerical representation using the Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency technique. Subsequently, the “cosine_similarity” function was applied to compute the cosine similarity between the transformed textual elements. Cosine similarity ranges from 0 to 1, with 1 indicating identical vectors and 0 indicating no similarity [21].

The text’s word count was determined using Microsoft Word (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). The built-in word count tool, accessible via the “Review” tab, calculated the total number of words [22, 23].

All statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS version 27 (IBM, New York, USA). The data normality was assessed with the Shapiro-Wilk test. Given the relatively small sample sizes (n < 30 per group) and the limitations of normality testing under these conditions, non-parametric methods were selected to reduce the risk of assumption violations [24]. Continuous data are represented as mean ±standard deviation, median (min.–max.) for non-normally distributed data, and categorical data as frequency. Between-group differences were computed with the Kruskal-Wallis test. Any possible correlation was investigated using the Spearman correlation coefficient. Post-hoc analysis was performed using the Bonferroni test. The significance level was 0.05.

Results

The Shapiro-Wilk test showed that FRE, FKGL, and SMOG scores were normally distributed (p > 0.05), while EQIP scores, DISCERN scores, and word count values were not (p < 0.05). Due to small sample sizes and non-normal distributions in several variables, non-parametric tests were applied [24].

The total word count, readability, reliability, and quality scores of the texts are summarized in Table II.

Table II

Comparative analysis of word count readability and quality of texts produced by ChatGPT vs. ACR

Readability

The mean SMOG score for all ACR fact sheets was 12.72 ±1.15, compared with 14.30 ±0.80 for ChatGPT-generated texts (p < 0.001). The mean FKGL score for ACR fact sheets was 11.4 ±1.42, compared with 12.57 ±1 for ChatGPT-generated texts. The mean FRE score for ACR fact sheets was 43.75 ±9.40, compared with 35.83 ±5.5 for ChatGPT-generated texts (p < 0.001).

Reliability and quality

The median DISCERN score for ACR fact sheets was 52 (min.–max.: 48–55), while the median score for ChatGPT-generated texts was 46 (min.–max.: 44–49; p < 0.001). The EQIP scores showed no significant difference between ACR fact sheets and ChatGPT-generated texts (p = 0.744).

Similarity and text length

The cosine similarity index values between ACR fact sheets and ChatGPT-generated texts ranged from 0.57 to 0.74, with an average of 0.69 ±0.05 (Table III). The median word count for ACR information pages was 450 (min.–max.: 361–553), compared to 1109 (min.–max.: 929–1,274) for ChatGPT-generated texts (p < 0.001).

Table III

Cosine similarity index values between texts produced by ChatGPT and ACR

Discussion

This study provides early empirical evidence that ChatGPT-generated texts on RDs are significantly less readable, longer, and less reliable than expert-authored materials such as ACR fact sheets. To our knowledge, this is the first study to benchmark ChatGPT’s educational content in rheumatology against validated patient resources, revealing both the potential and limitations of AI-generated health information.

A major issue identified was the readability gap. While ACR materials adhered to recommended standards for patient education, ChatGPT responses averaged a 12th-grade reading level, far exceeding the eighth-grade threshold considered suitable for most U.S. adults [25]. This poses a risk of misinterpretation, particularly among populations with limited health literacy [26]. Prior research has shown that even modest increases in linguistic complexity can impair comprehension and information recall, especially among patients managing chronic conditions [27, 28]. These findings highlight the need to embed readability constraints into AI outputs to ensure accessibility and safety for diverse patient groups.

Regarding quality, ACR fact sheets significantly outperformed ChatGPT outputs in DISCERN scores, indicating higher reliability and depth. Although EQIP scores were comparable, the discrepancy suggests that ChatGPT produces well-structured but often superficial content lacking evidence-based components. This supports previous concerns that ChatGPT’s fluency can mask factual inaccuracies or insufficient reasoning [29]. Given the 65% similarity between texts, these differences are not simply due to topic selection but reflect meaningful gaps in content depth, accuracy, and sourcing. Enhancing the clinical credibility of AI tools will require expert validation, transparent sourcing, and regular updates based on current medical guidelines to build trust and minimize misinformation.

Length was another key factor influencing readability. ChatGPT outputs were more than twice as long as ACR materials, contributing to lower readability scores. While length alone does not determine understanding, excessive verbosity can impair focus, elevate cognitive load, and reduce recall – especially among patients with chronic illnesses or limited health literacy [30–32]. Longer texts may also appear thorough while lacking clarity or prioritization. Furthermore, syntactic complexity, technical jargon, and disorganized structure – often present in AI outputs – compound these challenges [33]. Addressing this will require improved summarization algorithms and better integration of user-centered design principles in language model development. Techniques such as reinforcement learning with human feedback or domain-specific fine-tuning could help align AI outputs with medical standards for clarity and conciseness.

Despite these limitations, ChatGPT shows notable strengths when used in appropriate contexts. It has performed well on standardized medical assessments, demonstrating strong knowledge retrieval and clinical reasoning [34]. ChatGPT has been rated highly empathetic in patient communication, with patients often perceiving its tone as equivalent to that of physicians – even though experts continue to identify shortcomings in accuracy and depth [35]. Its use in clinical documentation has also been promising, particularly for drafting encounter summaries and reducing administrative workload [36]. A recent systematic review found that large language models offer value in tasks such as triage, summarization, and preliminary decision support – when outputs are supervised and constrained by domain knowledge [37]. These findings suggest that ChatGPT, though not suitable for unsupervised patient education, can complement healthcare delivery when embedded in expert-validated workflows.

Our findings also align with recent research in rheumatology showing a divergence between patient and expert evaluations of AI-generated responses. While patients frequently rate ChatGPT’s answers as clear and empathetic, clinical experts report gaps in factual accuracy, depth, and nuance [38]. This discrepancy raises concerns about patients’ ability to recognize the limitations of AI-generated information, particularly when responses appear polished and fluent [39]. In our study, ACR fact sheets outperformed ChatGPT across multiple quality domains despite moderate textual similarity, indicating that surface-level overlap does not equate to clinical reliability [40]. ChatGPT’s lower performance may stem from an inability to prioritize key clinical information, cite sources, or reflect expert judgment. These findings reinforce the importance of treating AI as a complement – not a replacement – for expert-developed educational materials.

As interest in AI-generated health tools grows [41], it remains essential to contextualize their role in healthcare delivery. While tools such as ChatGPT may offer convenient general insights, they are not substitutes for clinical judgment. They lack contextual sensitivity, diagnostic reasoning, and the ability to incorporate patient-specific details such as history, comorbidities, or evolving guidelines – elements critical to safe and effective care [42]. Both ChatGPT and the ACR advise users to consult healthcare professionals for diagnosis and treatment, emphasizing the continued need for clinician oversight in AI-augmented care models. In future, such tools should serve as adjuncts to professional care rather than standalone authorities.

Study limitations

This study has several limitations. First, ChatGPT outputs can vary based on model version, server conditions, and interaction context, all of which were standardized in this study but are subject to variability in real-world use. Second, while validated readability indices (e.g., FKGL, FRE, SMOG) were used, these tools measure only surface-level linguistic complexity and do not capture semantic understanding, cultural relevance, or engagement – factors vital to patient communication [32]. Third, although DISCERN and EQIP provide structured evaluation, both involve subjective scoring, which may introduce evaluator bias [43]. Fourth, the use of a single standardized prompt per condition aimed to enhance internal validity and replicate typical user behavior, though it limited the exploration of prompt variability [40, 44]. Finally, our sample included only 15 English-language RD topics, limiting the generalizability of findings across other specialties, languages, and patient populations. Future studies should assess AI content across prompt variations and model versions and incorporate feedback from clinicians and patients to evaluate clinical relevance, empathy, and trustworthiness in diverse contexts.

Conclusions

This study identified substantial differences in the readability, reliability, and length of ChatGPT-generated texts compared to expert-reviewed materials from the ACR. While ChatGPT outputs exhibited moderate textual similarity to ACR fact sheets, they were significantly more complex, less reliable, and markedly longer, raising concerns about accessibility and trustworthiness in patient education. These findings underscore that, in their current form, large language models are not a substitute for rigorously developed, clinician-reviewed educational content. However, generative AI tools may hold value as adjuncts to healthcare communication when used within well-defined parameters and under professional oversight. Future efforts should focus on improving the factual accuracy, readability, and personalization of AI-generated health information through expert validation pipelines, literacy-aware design constraints, and iterative evaluation frameworks involving both clinicians and patients. This study provides foundational evidence to inform the responsible integration of AI in patient education, particularly in complex chronic disease contexts such as rheumatology.