Introduction

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is a chronic inflammatory musculoskeletal disease associated with psoriasis, characterized by peripheral arthritis, enthesitis, dactylitis, and axial involvement. Apart from joint-related manifestations, PsA patients face a significantly increased burden of comorbidities, particularly cardiovascular (CV) diseases, metabolic syndrome, and mental health disorders, all of which contribute to reduced quality of life and increased mortality [1–3].

Several studies have demonstrated that PsA patients have a higher risk of CV events and mortality compared to the general population. Specifically, PsA patients exhibit a 43% higher risk of CV mortality, with a standardized mortality ratio of approximately 1.43, similar to that observed in rheumatoid arthritis [4, 5]. This increased risk is attributed to both traditional CV risk factors – such as obesity, hypertension (HT), diabetes mellitus (DM), and dyslipidemia – and the systemic inflammatory burden [6].

Systemic inflammation plays a central role in accelerating atherosclerosis and promoting endothelial dysfunction, thereby increasing CV risk in PsA patients [7]. Consequently, adequate control of inflammation is critical not only for improving articular outcomes but also for reducing CV morbidity and mortality.

Physical activity (PA) is widely recognized as a cornerstone of non-pharmacological management in chronic inflammatory arthritis, including PsA. Regular PA has well-established benefits in improving functional capacity, reducing fatigue, and lowering CV risk in both the general population and among patients with rheumatic diseases [8–10]. Despite these benefits, PsA patients often exhibit lower PA levels compared to healthy controls, largely due to pain, fatigue, joint damage, and psychological barriers [11–13].

The primary objective of this study was to evaluate the relationship between PA levels and CV risk factors in patients with PsA.

The secondary objective was to identify distinct subgroups of PsA patients based on PA patterns and associated comorbidities using latent class analysis (LCA), in order to better understand potential targets for personalized interventions.

Material and methods

Study design and participants

This cross-sectional study included consecutive adult patients (≥ 18 years) diagnosed with PsA according to the Classification Criteria for Psoriatic Arthritis (CASPAR) criteria [14], regularly followed at the outpatient rheumatology clinic of the Institute of Rheumatology in Belgrade, Serbia.

Exclusion criteria included: severe comorbid conditions precluding PA assessment (e.g., advanced heart failure, severe neurological deficits), active malignancy, and severe musculoskeletal disorders significantly affecting mobility (e.g., major limb amputation, advanced osteoarthritis of the hip or knee).

Clinical and demographic data

Demographic data included age, sex, educational level, and employment status. Disease activity was assessed using the clinical Disease Activity Index for Psoriatic Arthritis (cDAPsA) score, a validated composite score that combines tender joint count (68 joints), swollen joint count (66 joints), patient global assessment (0–10 cm visual analog scale), and patient pain assessment (0–10 cm visual analog scale), without including C-reactive protein (CRP). The cDAPsA scores allow classification into remission (≤ 4), low disease activity (> 4 to ≤ 13), moderate disease activity (> 13 to ≤ 27), and high disease activity (> 27), enabling precise categorization of disease control in PsA patients. Treatment information was collected, including current and previous use of biologic or targeted synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs – e.g., tumor necrosis factor TNF inhibitors, Janus kinase inhibitors (JAKi) and glucocorticosteroids – with duration of therapy recorded in years. Educational attainment and employment status as well as marital status were included to explore potential socioeconomic and behavioral influences on PA levels and LCA membership.

Assessment of physical activity

Physical activity levels were evaluated using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire Short Form (IPAQ-SF), a widely used and validated self-report tool designed to assess PA in adults across different populations [15].

The IPAQ-SF includes seven items assessing the frequency and duration of vigorous, moderate, and walking activities during the past 7 days. Time spent sitting was also recorded to capture sedentary behavior.

Total PA was expressed in metabolic equivalent task (MET)-minutes per week:

Metabolic equivalent task-minutes per week were calculated by multiplying activity duration (in minutes) by the corresponding MET value (vigorous = 8.0, moderate = 4.0, walking = 3.3) and frequency (days per week).

According to IPAQ-SF scoring guidelines, patients were categorized as:

Assessment of cardiovascular risk factors

Cardiovascular risk factors were recorded based on patient history, clinical examination, and laboratory data, including:

HT (blood pressure ≥ 140/90 mmHg or current antihypertensive therapy),

type 2 DM ([DMT2] previous diagnosis or antidiabetic therapy),

dyslipidemia (total cholesterol ≥ 5.2 mmol/l, low-density lipoprotein [LDL] ≥ 3.4 mmol/l, triglycerides ≥ 1.7 mmol/l, or lipid-lowering therapy),

obesity (body mass index [BMI] ≥ 30 kg/m²),

current or former smoking status.

Assessment of fatigue, functional status, and other questionnaires

Fatigue was evaluated using the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy Fatigue Scale (FACIT-F) [16]. The FACIT-F is a 13-item questionnaire assessing fatigue and its impact on daily activities and function over the past week, using a 5-point Likert scale. Total scores range from 0 to 52, with higher scores indicating less fatigue. Scores below 30 are commonly interpreted as indicating severe fatigue.

Functional status was assessed using the Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index (HAQ-DI) [17]. The HAQ-DI is a 20-item instrument covering eight domains of daily activities, scored from 0 (“no difficulty”) to 3 (“unable to do it”). The final score ranges from 0 to 3, with higher scores reflecting greater disability.

Depression symptoms were assessed using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), a 9-item self-report instrument designed to screen, diagnose, and measure the severity of depression. Each item is scored from 0 (“not at all”) to 3 (“nearly every day”) based on the past two weeks, with total scores ranging from 0 to 27. Scores were categorized as minimal (0–4), mild (5–9), moderate (10–14), moderately severe (15–19), and severe depression (20–27) [18].

Anxiety symptoms were assessed using the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), a 21-item self-report tool measuring common anxiety symptoms experienced over the past week. Each item is scored from 0 (“not at all”) to 3 (“severely”), with a total score range of 0 to 63. Scores were categorized as minimal (0–7), mild (8–15), moderate (16–25), and severe anxiety (26–63) [19].

Risk of sarcopenia was assessed using the SARC-F questionnaire, which evaluates strength, assistance in walking, rising from a chair, climbing stairs, and falls. Each item is scored from 0 to 2, with a total score range from 0 to 10. A score ≥ 4 was considered indicative of probable sarcopenia [20].

Kinesiophobia was assessed using the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia (TSK), a 17-item self-report questionnaire measuring fear of movement or (re)injury. Each item is rated on a 4-point Likert scale, with total scores ranging from 17 to 68. Scores above 37 indicate high kinesiophobia [21].

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize demographic and clinical characteristics. Continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median with interquartile range (IQR), as appropriate. Categorical variables were presented as counts and percentages.

Comparisons between groups (based on PA levels) were performed using the χ2 or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables, and ANOVA or Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables, depending on data distribution.

Latent class analysis was conducted to identify unobserved subgroups (latent classes) based on PA levels and associated CV and psychosocial risk factors (e.g., HT, DMT2, obesity, smoking status, PHQ-9 scores, BAI scores, HAQ-DI, SARC-F scores, TSK scores, education, marital status, etc.).

Latent class analysis models with different numbers of classes were fitted, and the optimal number of classes was selected based on the lowest Bayesian information criterion, Akaike information criterion, entropy, and clinical interpretability. Patients were assigned to classes based on their highest posterior class membership probability.

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). A two-sided p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 62 patients with PsA were included, with a nearly equal sex distribution: 32 females (51.6%), 30 males (48.4%). The mean age was 44.5 ±10.3 years, with no significant sex difference (females: 42 years, males: 47 years, p > 0.05). Median disease duration was 9 years (IQR: 5–15), and the median treatment duration was 6 years (IQR: 3–15).

Most patients (90%) were treated with biologics or JAKi, with a median duration of 1 year (IQR: 0.5–5). Glucocorticosteroids therapy was used in 80% of patients, with a median duration of 2.2 years (IQR: 0.25–5). Overall, 80% of patients were in remission or had low disease activity according to cDAPsA scores. In our cohort, the prevalence of obesity was 51.6% (32 patients), DMT2 12.9% (8 patients), HT 23% (16 patients), and dyslipidemia 30% (19 patients).

Physical activity levels

Physical activity was classified as low in 12 patients (19.4%), moderate in 42 patients (67.7%), and high in 8 patients (12.9%). Median MET-minutes per week significantly differed among groups (p < 0.001), with the lowest in the low PA group (235 ±184 MET-min/week) and the highest in the high PA group (4552 ±1452 MET-min/week).

Patients with low PA were more likely to be over 60 years of age (p = 0.04) and exhibited significantly higher fatigue levels (FACIT-F median score 29 ±7. vs. 38.3 ±6.7 in moderate PA and 43 ±6.4 in high PA, p = 0.01), as well as greater functional impairment (HAQ-DI median score 0.9 vs. 0.1 and 0.25, p = 0.03).

While differences in the prevalence of HT, DMT2, dyslipidemia, and obesity across PA groups did not reach statistical significance, higher rates of obesity and dyslipidemia were observed in the low PA group. For example, obesity was present in 66.7% of patients with low PA, compared to 42.9% in the group with moderate PA. Dyslipidemia was also common in the low PA group (33%).

Psychosocial outcomes and sarcopenia risk

Patients with lower PA levels reported higher depression symptoms (PHQ-9 median score 6.7 ±3 vs. 5.6 ±5 and 3.25 ±2, p = 0.32) and greater kinesiophobia (TSK median score 39 vs. 38 and 38, p = 0.21). Higher SARC-F scores were observed in the low PA group (median 3 ±2.6 vs. 1.86 ±2 and 1.25 ±0.9, p = 0.13), indicating an increased risk of sarcopenia (Table I).

Table I

Characteristics of patients with different levels of PA

[i] BMI – body mass index, cDAPsA – Clinical Disease Activity Index for Psoriatic Arthritis (remission ≤ 4; low disease activity > 4 to ≤ 13; moderate disease activity > 13 to ≤ 27; and high disease activity > 27), DMT2 – diabetes mellitus type 2, FACIT – Fatigue Scale (score lower than 30 indicates serious fatigue), GCs – glucocorticosteroids, JAKi – Janus kinase inhibitors, HAQ – Health Assessment Questionnaire (0 = no incapacity, 3 = full incapacity), HT – hypertension, MET – metabolic equivalent of task, PA – physical activity (low PA = 0–600 MET minutes per week, moderate PA = 600–3,000 MET minutes per week, high PA = more than 3,000 MET minutes per week), PHQ9 – Patient Health Questionnaire for depression (score 0–4: none or minimal, 5–9: mild, 10–14: moderate, 15–19: moderately severe, 20–25: severe depression), SARC-F (scores > 4 indicate risk of sarcopenia), TSK – Tampa scale of kinesiophobia (scores > 37 predict kinesiophobia).

Latent class analysis

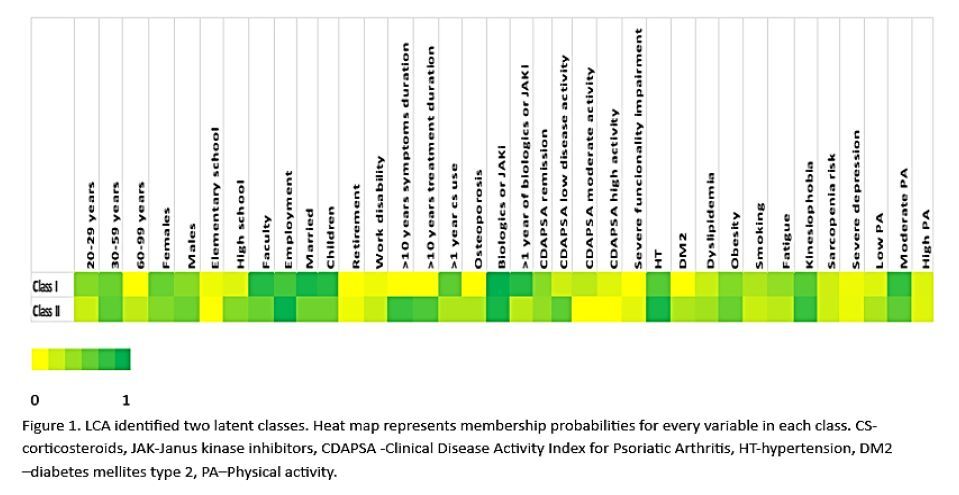

Latent class analysis identified two distinct latent classes.

Class I included predominantly younger adults (20–59 years), with a slight female predominance (56%). Most patients had a university education (82%) and were employed (69%). Moderate PA was most frequent (75%). Cardiometabolic risk factors were lower in this class, with obesity in 46%, smoking in 30%, and relatively low rates of HT, DMT2, and dyslipidemia. Approximately 12% of this class had high disease activity, which correlated with increased fatigue (40%). Overall, this class represented a younger, more active, and metabolically healthier subgroup.

Class II included a broader age range, with 23% of patients aged ≥ 60 years and a slight male predominance (54%). The proportion with a university degree was lower (55%), though employment remained high (93%). Physical activity levels were lower in this class, with 30% reporting low PA and 60% moderate PA. Cardiometabolic risk factors were more prevalent, including HT (86%), DMT2 (30%), obesity (56%), and dyslipidemia (35%), while smoking was less frequent (20%). Functional impairment was higher (10%), and serious depression was more common (7%). Notably, kinesiophobia (74%) and sarcopenia risk (19%) were elevated, suggesting greater physical and psychological barriers to PA in this subgroup. This class thus represented an older, higher-risk, and less active population (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1

Latent class analysis identified 2 latent classes. Heat map membership probabilities for every variable in each class.

cDAPsA – clinical Disease Activity Index for Psoriatic Arthritis, DM2 – diabetes mellitus type 2, GCs – glucocorticosteroids, HT – hypertension, JAKi – Janus kinase inhibitors, PA – physical activity.

Discussion

In this cross-sectional study, we comprehensively assessed PA levels and their associations with CV risk factors, psychosocial parameters, and functional outcomes in patients with PsA. By additionally employing LCA, we identified distinct patient subgroups, highlighting important differences in metabolic, behavioral, and psychological profiles. These findings reinforce the notion that optimal PsA management extends beyond pharmacological control of inflammation, emphasizing the importance of holistic, personalized approaches.

Physical activity levels and clinical outcomes

Most PsA patients in our cohort reported moderate PA levels (67.7%), while nearly one-fifth exhibited low PA (19.4%). These proportions are comparable to a large international study where approximately 30% of PsA patients were classified as physically inactive using IPAQ criteria [22]. Similar trends were observed in the study by Sokka et al. [23], where up to 41% of patients with inflammatory arthritis did not meet minimum WHO recommendations for weekly activity. However, our higher proportion of moderate PA may reflect the younger age and lower disease activity in our cohort.

Importantly, lower PA levels were associated with older age, higher fatigue (lower FACIT-F scores), and greater functional impairment (higher HAQ scores). These findings are consistent with prior evidence that pain, fatigue, and aging-related sarcopenia contribute to reduced activity levels in inflammatory arthritis [23].

The latest 2023 European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology recommendations strongly advocate for integrating regular PA – including aerobic, strengthening, flexibility, and neuromotor exercises – into standard care for all patients with inflammatory arthritis, including PsA [24]. Our results strongly support this recommendation, demonstrating that higher PA levels correspond to improved fatigue and functional outcomes.

Mechanistically, PA exerts anti-inflammatory effects by reducing levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF and interleukin-6 (IL-6) while increasing anti-inflammatory mediators such as IL-10 [25, 26]. Furthermore, PA improves endothelial function, reduces oxidative stress, and enhances insulin sensitivity, collectively mitigating CV risk [27]. These molecular mechanisms suggest that PA acts as a “systemic anti-inflammatory treatment,” complementing pharmacologic therapy to improve overall disease outcomes.

Despite advances in biologic and targeted therapies, CV risk remains high in PsA patients, as shown by the high prevalence of obesity, HT, and dyslipidemia in our cohort. These findings align with previous studies indicating that PsA patients have a 43% higher CV mortality risk compared to the general population [4].

At a molecular level, chronic systemic inflammation mediated by cytokines such as TNF, IL-6, and IL-17 promotes endothelial dysfunction and accelerates atherosclerosis [28]. Additionally, adipokines released from visceral fat (e.g., leptin, resistin) synergize with these cytokines, amplifying vascular inflammation and metabolic dysfunction [29]. Oxidative stress further exacerbates endothelial damage, perpetuating the cycle of vascular injury [30].

Obesity was present in more than half of our PsA cohort, highlighting the significant metabolic burden. Apart from being a major CV risk factor, obesity is associated with higher disease activity and poorer treatment response in PsA [31]. Recent studies suggest that glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs), originally developed for DMT2 and obesity, possess anti-inflammatory properties by modulating immune cell activity and reducing systemic pro-inflammatory cytokines [32, 33]. Preliminary evidence indicates that GLP-1RAs may help reduce disease activity in patients with obesity-associated inflammatory arthritis, offering a promising avenue that combines metabolic and inflammatory control [34]. These findings underscore the importance of comprehensive weight management strategies in PsA, potentially integrating pharmacologic and lifestyle approaches to optimize outcomes.

Psychosocial factors and barriers to activity

Patients with lower PA levels reported higher depression symptoms (PHQ-9), greater kinesiophobia (TSK), and higher SARC-F scores, indicating sarcopenia risk. These findings reflect the complex interaction between psychological barriers and physical inactivity. In PsA, kinesiophobia may be under-recognized but significantly affects PA – particularly in older or fatigued patients with a psychosocial burden. Unlike axSpA, where movement often relieves symptoms, PsA patients may associate activity with pain or damage, especially with enthesitis. Fear of movement and pain avoidance can lead to deconditioning, perpetuating fatigue and disability in a vicious cycle [35, 36]. Addressing these psychosocial and behavioral barriers is crucial. Multidisciplinary strategies involving physiotherapists, psychologists, and patient educators may help overcome these challenges and improve adherence to PA interventions.

Emerging evidence suggests that neuroinflammation plays a pivotal role in the development of depression and anxiety in chronic inflammatory diseases, including PsA. Pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF, IL-6, and IL-17 can cross the blood–brain barrier, activate microglia, and disrupt neurotransmitter metabolism, contributing to central nervous system inflammation and altered neuroplasticity [37, 38]. Recent neuroimaging studies in PsA and psoriasis have demonstrated altered activation in brain regions involved in pain processing and emotion regulation, including the insula, anterior cingulate cortex, and prefrontal cortex [39, 40]. These findings support the hypothesis of central sensitization and help explain the high prevalence of depression, anxiety, and fatigue in these patients. This neuroimmune interaction further underscores the importance of comprehensive management strategies that address both systemic and neuropsychological aspects of PsA. Interventions promoting PA may not only reduce peripheral inflammation but also modulate neuroinflammatory pathways, potentially improving mood and cognitive outcomes [41, 42].

Latent class analysis: implications for personalized care

Latent class analysis identified two distinct classes:

class I, characterized by younger, more active patients with lower metabolic risk, higher educational attainment, and a lower psychosocial burden,

class II, including older patients with higher rates of cardiometabolic comorbidities, lower PA levels, and greater psychological and functional barriers.

These results underscore the heterogeneity of PsA and the need for personalized, stratified care approaches. Patients in class II, in particular, may benefit from targeted interventions addressing both physical and psychological domains to promote PA and improve overall outcomes.

Phenotype and extra-articular manifestations

It is also important to consider that PA patterns may differ according to PsA phenotype. Patients with predominant axial involvement or severe peripheral joint damage might face greater physical limitations [42]. In our study, most patients had predominantly peripheral arthritis, and none had extra-articular manifestations such as uveitis, inflammatory bowel disease, or systemic organ involvement apart from skin psoriasis. This relatively “mild” disease profile may partially explain the higher proportion of patients achieving moderate activity levels.

Clinical implications

Our findings reinforce the importance of integrating PA promotion into PsA management, emphasizing its dual benefits for both musculoskeletal and CV health. The “kill two birds with one stone” concept is clearly illustrated: PA not only improves joint-related outcomes (fatigue, function) but also mitigates CV risk through multiple systemic mechanisms.

In our country, patients with PsA have the right to undergo inpatient rehabilitation once per year free of charge. During these rehabilitation programs, patients learn basic exercise techniques as part of a comprehensive multimodal approach, including physiotherapy, hydrotherapy, and patient education. This structured opportunity supports safe movement, strengthens self-efficacy, and encourages long-term adherence to active lifestyles. Moreover, the National Association of Patients with Rheumatic Diseases has initiated community workshops focused on activities such as yoga and tai chi. These gentle, low-impact exercise modalities have been shown to improve flexibility, balance, and mental well-being while reducing fear of movement. Such community-based initiatives represent an important step in translating evidence-based recommendations into practice, empowering patients to adopt a more active lifestyle and ultimately improving both physical and psychological outcomes.

Strengths and limitations of the study

Key strengths of our study include comprehensive assessment using validated questionnaires, analysis of both physical and psychosocial variables, and the use of LCA to uncover hidden patient subgroups. However, limitations include its cross-sectional design, which precludes causal inference, and reliance on self-reported measures (e.g., IPAQ-SF, PHQ-9), potentially introducing recall and social desirability biases. Although all our patients had peripheral PsA, we did not perform detailed clinical phenotyping into subgroups (e.g., asymmetric oligoarticular, symmetric polyarticular, distal interphalangeal–predominant, axial). Additionally, we used cDAPsA rather than including objective inflammatory markers such as CRP. The relatively small sample size may also limit the generalizability and statistical power for subgroup analyses.

Future directions

Longitudinal studies are needed to evaluate causality and the long-term impact of PA interventions on CV outcomes and disease activity in PsA. Incorporating objective measures of PA (e.g., accelerometers) and exploring personalized exercise interventions tailored to specific LCA-derived subgroups could further enhance future research and clinical practice.

Conclusions

Lower PA levels in PsA patients are associated with increased fatigue, higher functional impairment, and greater cardiometabolic and psychosocial burden. Our findings highlight the need for integrated management approaches that combine pharmacologic inflammation control with tailored PA promotion and psychological support. Such strategies hold the potential to improve both joint and CV outcomes, embodying a truly holistic approach to PsA care.