Introduction

Greater trochanter pain syndrome (GTPS) is a very common problem in society, causing pain in the lateral part of the hip [1]. Bicket et al. [2] reported an incidence of GTPS of 3.29 patients per 1,000 per year. It can affect patients of any age (most often between 40 and 60 years of age) and is primarily associated with a sedentary, overloading lifestyle with a lack of regular physical activity, obesity, overweight, and female gender (3–4 times more often). In addition, GTPS can be secondary to other musculoskeletal pathologies such as osteoarthritis (gonarthrosis, coxarthrosis, spondyloarthrosis) or rheumatic diseases [1–3].

It manifests primarily as pain in the lateral part of the hip, with or without prominence toward the lumbarsacral spine, but also through the iliotibial band toward the knee on the lateral aspect of the thigh. Patients have difficulty walking upstairs or getting up from a chair, and report pain when sleeping on the affected side [4].

Greater trochanter pain syndrome is two-fold. It may be associated with inflammation of the bursa or peritrochanteric bursae and/or enthesopathy (tendinopathy), i.e. inflammation of the muscle attachment to the bone in the area of the gluteus medius and/or minimus tendon. Due to the fact that there are many bursae within the greater trochanter area, it is possible to distinguish those located between the various muscle tendons, which may undergo pathological changes [5].

In the vicinity of the greater trochanter, several bursae are present, including:

the subgluteus maximus bursa – located above the greater trochanter and below the tensor fascia lata,

the subgluteus medius bursa – located deep in the distal insertion of the gluteus medius tendon, and covering a region of the superior part of the lateral facet of the greater trochanter of the proximal femur,

the subgluteus minimus bursa – located in the area of the anterior facet of the greater trochanter of the proximal femur, deep in the gluteus minimus tendon.

In addition, within the greater trochanter there can be distinguished the subcutaneous trochanteric bursa, bursa of the piriformis muscle, sciatic bursa of the obturator internus, subtendinous bursa of the obturator internus, intermuscular gluteal bursae, and others [6].

Currently, it is believed that inflammation within the bursae is secondary to tendinopathy. Depending on the degree of progression of the changes, the clinical picture may vary. Typically, the patient reports pain in the lateral hip and buttock area, and in more advanced lesions the pain radiates through the iliotibial band. Sometimes the pain radiates towards the inguinal region, so it is necessary to determine whether the cause of the pain is coxarthrosis [6, 7]. To differentiate, a standing X-ray of the pelvis is taken and the hip joints are assessed. However, it may also be the case that GTPS is a complication of coxarthrosis and the X-ray will show radiological changes characteristic of coxarthrosis, and the patient will also have GTPS [8].

The greater trochanter bursae, due to their superficial location and proximity to large tendons, are prone to inflammation. The bursa directly above the trochanter separates it from the tendon of the gluteus medius muscle, which runs above it on the side of the hip, and facilitates the work of the quadriceps femoris muscle [6].

In addition to inflammation of the bursae, changes with the character of enthesopathy, i.e. overload and degenerative changes of the tendon attachment, are observed. The symptoms similar to enthesopathy most often derive from the subgluteal bursae [6, 7].

Tendinopathy is a chronic, painful tendon disease characterized by histological modifications such as disorganization of collagen (COL) fibrils, increased non-collagenous components of the extracellular matrix, increased proteoglycans and glycosaminoglycans [7].

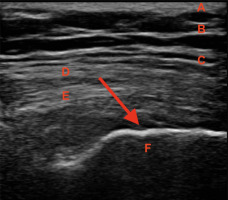

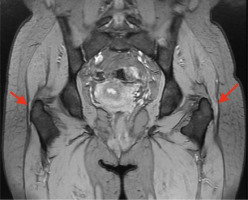

The diagnosis is made on the basis of history (risk factor assessment) and physical examination. Palpation assessment of the greater trochanter plays a key role. The patient lies on his or her side with the lower limb straight at the hip and knee. It is always advisable to evaluate the right and left sides. In addition, the FABER test is also applicable in the diagnosis [4, 9]. Imaging diagnostics can be used to confirm the diagnosis. Ultrasonography (Fig. 1), X-ray (Fig. 2) and magnetic resonance imaging (Fig. 3) are applicable [10, 11].

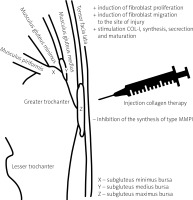

Fig. 1

GTPS in an ultrasound image (indicated with a red arrow) showing uneven outline of the greater trochanter and subgluteus medius bursitis: A – skin, B – subcutaneous tissue, C – tensor fascia lata, D – gluteus maximus, E – gluteus medius, F – greater trochanter

Fig. 2

Greater trochanter pain syndrome in standing pelvic X-ray (indicated with red arrows) – uneven outline of the greater trochanter, visible calcifications and osteophytes on the right and left sides.

Fig. 3

Greater trochanter pain syndrome in magnetic resonance imaging (indicated with red arrows) – visible swelling and inflammation. In the area of the right greater trochanter, smaller inflammatory changes and tissue swelling are visible. More severe changes are visible on the left side

Physical therapy, kinesio-therapy, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are used to treat GTPS. Glucocorticosteroids (GCs) injections in the greater trochanter region are also frequently used. Based on an analysis of 76 publications on the treatment of GTPS, it appears that infiltrations with GCs and shockwave therapy have the greatest efficacy, although this therapy has not been compared to sonotherapy or transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation [12, 13]. According to Mani-Babu et al. [13], shock wave therapy was found to be more effective than GCs therapy.

Glucocorticosteroid injection therapy has analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects. But it has its downsides. It can cause elevated blood pressure values in patients with hypertension. It can cause elevated blood glucose in diabetic patients. In addition, GCs therapy weakens immunity and is contraindicated in athletes [14].

In their randomized study, Brennan et al. [15] found no significant difference between the use of GCs injections and dry needling in the course of GTPS.

In addition, injection therapy with platelet-rich plasma (PRP) is worth mentioning, but the literature to date presents poor-quality evidence on the effectiveness of this therapy in the course of GTPS [16].

In view of the above, medicine is continually seeking new yet safe therapeutic solutions in the course of musculoskeletal pathologies, including GTPS. One of these therapies is injection COL therapy. Papers published in recent years emphasize not only the effectiveness, but also the safety of injectable COL-I [17, 18].

The aim of this article is to evaluate the use of injectable COL therapy in the course of GTPS as a new therapeutic approach.

Causes of greater trochanter pain syndrome

Greater trochanter pain syndrome can be secondary to osteoarthritis, especially in the course of gonarthrosis or coxarthrosis. In the process of degenerative changes, the articular cartilage is degraded, thereby narrowing the joint space. As a consequence, there is shortening of the lower limb and unilateral overload. However, GTPS has not been linked to lower limb length asymmetry based on the literature [19]. The load generated increases tension of periarticular soft tissues, including in the greater trochanter as a compensatory mechanism. This leads, in the course of developing arthrosis, to an abnormal gait or limp mechanism. A potential consequence of this is the development of degenerative disease [2, 6].

Moreover, tendinopathies and bursitis are observed in the course of rheumatic diseases, e.g. rheumatoid arthritis [20].

In addition, it is worth mentioning spinal pathologies, symptomatic discopathy with neuralgia-like pain radiation to the lower limb or spondyloarthrosis. Pain conditions of the lumbar spine and symptoms of femoral or sciatica cause abnormal gait and limping, resulting in asymmetric loading at the muscle attachments to the greater trochanter and the development of GTPS [21].

Therefore, an important aspect in the diagnosis of GTPS is to determine whether the pathology is primary or a complication of another disease, including osteoarthritis. Additionally, some patients after hip replacement may develop GTPS, especially when a posterior surgical approach is used. However, postoperative satisfaction and functional outcomes were significantly lower in patients with GTPS, regardless of approach [22].

Collagen type I

The human body is made up of 5–6% COL. Nearly 90% is composed of COL-I. In the course of tendinopathy of the greater trochanter, micro-injuries most often occur in the tendons of the small and/or medium gluteal muscle [2, 18].

Tendons play a key role in the musculoskeletal system, transmitting forces generated by muscle contraction to the skeleton. Their mechanical properties are based on the structure and composition of the extracellular matrix (ECM), consisting mainly of COL-I [23, 24]. Tenocytes are specialized fibroblasts located in tendons, distributed between COL fibers, responsible for metabolic activity and tendon structure [25]. They participate in COL turnover pathways and act as mechanosensors, playing a key role in modifying gene expression of ECM components in response to mechanical forces acting on tendons [26–28].

The unique structure and composition of tendons provide them with their characteristic mechanical stability, and COL-I is the most important factor in the mechanical strength of tendons. Tenocytes are responsible for the synthesis and degradation of COL and all components of the ECM [24].

In order to counteract physiological and pathological tendon degeneration, an injectable compound based on porcine COL-I (100 µg/2 ml ampoules) was developed. In addition, it contains ascorbic acid, magnesium gluconate, pyridoxine hydrochloride, riboflavin, thiamine hydrochloride, NaCl and water as excipients [29, 30].

Based on the studies, COL-I in combination with additional substances has a multidirectional effect on gluteal muscle tenocytes. It activates the following mechanisms (Fig. 4):

induction of fibroblast proliferation,

induction of fibroblast migration to the site of injury,

stimulation of COL-I synthesis, secretion and maturation,

inhibition of the synthesis of type I metalloproteinase (MMP-1), which degrades COL [24].

Newly synthesized COL undergoes crosslinking, which is an important condition for its maturation, providing tendon strength, stabilization of COL fibrils and increased tensile strength of tendons, especially when they are overloaded due to excessive work [31].

Moreover, COL content is the result of a finely regulated dynamic balance between its synthesis and degradation driven by MMPs; tendon strength is strongly dependent on degradation pathways. Type I metalloproteinase (MMP-1), capable of cleaving the intact COL triple helix, is involved in COL degradation [32].

The role of MMP-1 is reinforced by the previously demonstrated inverse correlation between MMP-1 gene/ protein expression and the amplitude of tendon mechanical tensile loading, suggesting that low levels of MMP-1 lead to a more stable and less vulnerable tendon structure [33].

Metalloproteinase activation and activity are regulated by tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase (TIMP), where TIMP-1 is the main inhibitor of MMP-1. In a study by Randelli et al. [24], it was found that COL-I had no effect on MMP-1 and MMP-2. A significant increase in COL-I-induced TIMP-1 gene expression was observed after 24 hours, with the up-regulation trend continuing at 72 hours. This result leads to the hypothesis that COL-I is able to stimulate COL secretion by tenocytes, increasing COL content in tendons, and the increase in COL is facilitated by inhibition of its degradation [34].

Injection scheme

The standard procedure is to perform injections within the greater trochanter into the inflamed bursa and/or pathologically altered tendon [3]. These procedures can be performed under ultrasound guidance for precise administration of COL-I. For more experienced practitioners, an ultrasound machine is not necessary [30]. Palpation examination immediately before the injection procedure is crucial. The patient lies in a side-lying position with the lower extremities straight at the hip and knee. The doctor looks over the greater trochanter for the most painful points, known as trigger points. Using COL-I (2 ml ampoule), an average of 4–5 injections are performed at one time, applying about 0.4–0.5 ml of the product per injection point. Injections are made directly into the bursa/bursae and/or tendon insertion. In chronic lesions, such treatment is performed once a week, at least in 5 repetitions [29, 35].

After COL injection treatment, physiotherapy of the area (especially movement therapy), massages, and hot baths are not recommended for 1–2 days due to the risk of stimulating the circulation of the treatment area and faster absorption of the injected product into the bloodstream [29, 35].

The injection itself can play quite an important role by stimulating receptors in the skin and subcutaneous tissue, causing activation of auto-repair mechanisms, stimulation of the immune system, an increase in inflammatory mediators and thus the repair of pathologically altered tissues [3].

The studies available in the literature report on the effectiveness of injection therapy alone, such as acupuncture or dry needling. In the proposed treatment concept, therapeutic effects should be expected from a dual mechanism of action, both mechanical and chemical [29, 35].

Safety of injection collagen therapy

Based on the literature to date on the use of COL-I and the injection technique in the greater trochanter, it appears that this form of treatment for GTPS is safe [3, 35]. Due to the high similarity of COL-I, about 95–97%, this risk of allergy is definitely low. It should be noted that COL-I is of natural origin, not synthetic [36, 37].

In addition, the injection technique is safe due to the fact that the injected anatomical structures (bursa or tendons) lie in a relatively shallow position under the skin, and there are no significant anatomical structures in the way [29, 35]. Attention should be paid to the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve, but there are thin branches of the nerve in this area, and the risk of its damage is not great [38]. Patients taking chronic anticoagulants may experience post-injection subcutaneous hematoma within the injection site [39].

Based on the existing literature, the use of injectable COL-I seems to be safe, and side effects from COL applications in enthesopathies and bursopathies appear to be rare, but their frequency has not been fully reported [18, 29].

Discussion

As there are no studies in the available literature showing the use of COL-I in GTPS, in vivo, this article is expected to be the first paper on this topic. In addition, it is also expected to show clinicians a new pathway in injection treatment in the course of GTPS.

In addition to the mechanisms of action of COL-I, a study by Randelli et al. [24] published in 2018 showed new therapeutic options in the course of GTPS. The study evaluated the effects of COL-I on cultured human post-tendon muscle tenocytes to understand how this compound can affect tendon biology and healing. The results showed that tenocytes cultured in a COL-I environment have an increased proliferation rate and migration potential. In addition, COL-I preparation affected the induction of COL-I secretion and the mRNA level of tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinases (MMP)-1. These results suggest that injectable COL-I may be effective in the conservative treatment of GTPS, given its effects on gluteal muscle tenocytes. Importantly, this study is ex vivo.

A follow-up to the above study was published in 2020 [40] by the same author and associates. The goal of this study was to analyze whether COL-I-induced effects were explained based on mechanisms related to mechanotransduction. This phenomenon is manifested through the ability of cells to translate mechanical stimuli into biochemical signals that can ultimately affect gene expression, cell morphology and cell fate. Tenocytes are responsible for the mechanical adaptation of tendons, reshaping mechanical stimuli imposed during mechanical loading, thereby affecting ECM homeostasis. Overall, COL-I, acting as a mechanical scaffold, can be an effective therapeutic, regenerative tool to promote tendon healing in tendinopathies.

Since there are no studies in the available literature on the use of COL-I in the course of GTPS, it is worth mentioning other studies that show both the safety and efficacy of injectable COL-I in the course of other tendinopathies.

A pilot study by Corrado et al. [41] published in 2019 assessed the effect of COL injections on the level of pain intensity and disability in patients with tennis elbow, thus testing whether there is a basis for conducting a randomized, controlled trial. The study included 50 patients who received 5 injection treatments at weekly intervals. This injection regimen is also proposed in the course of GTPS treatment. The Patient-Rated Tennis Elbow Evaluation questionnaire was used for assessment. Follow-up after 1 month and after 3 months showed the effectiveness of injectable COL therapy in lateral epicondylitis.

In another study by Corrado et al. [42], published in 2020, they evaluated the effectiveness of injectable COL in a supraspinatus muscle tendon injury. Ultrasonography showed gradual healing of the partial-thickness injury and regeneration of the tendon structure. This was the first study on ultrasound-guided injection of COL-I in the treatment of partial thickness rotator cone injury, which provides a foundation for further research in the field of injured tendons and tendinopathies.

A further study by Corrado et al. [43], published in 2020, evaluated the effectiveness of COL injections in the treatment of plantar fasciopathy in runners. The injection procedure was performed once a week, in 4 repetitions, under ultrasound monitoring. The Visual Analogue Scale, the American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society Ankle-Hindfoot Scale, and pressure algometry were used to evaluate the effects of COL injections after 1 and 3 months of follow-up. Despite the limitations of this study (especially in terms of the small group of patients), the positive results may provide a starting point for further clinical trials in the treatment of various tendinopathies.

Also worth mentioning is a randomized study by Godek et al. [44] published in 2022. This study investigated the use of various injection therapies with partial-thickness rotator cuff injuries (PTRCI) and included 90 patients, divided into 3 groups: group A (n = 30) – COL-I with PRP, group B (n = 30) – COL-I, group C (n = 30) – PRP. In all patients, injections were performed into the shoulder under ultrasound control at weekly intervals, in 3 repetitions. Observations and assessments were made after 6, 12 and 24 weeks. The study showed that combination therapy with COL-I and PRP in PTRCI has similar efficacy to monotherapy with COL-I or PRP. Thus, the use of injectable COL-I in PTRCI is justified.

The above studies used a standard injection regimen commonly followed in chronic tendinopathy-like pathologies, so in this article the proposed injection regimen is once a week, in a minimum of 5 repetitions. Of course, more injection treatments can be performed when using COL-I.

Another important issue in the treatment of musculoskeletal pathologies, including GTPS, is the safety of the therapy. Injection GCs therapy, which is often used, has its advantages, but also several disadvantages. We try to avoid administering GCs in adolescents or young adults if it is not absolutely necessary. The same problem applies to athletes, especially those practicing a sport professionally. Glucocorticosteroids in this case are contraindicated. Therefore, injectable COL therapy can be an alternative in the treatment of GTPS for this group of patients. In addition, in the course of osteoarthritis, we deal with elderly patients. In this group of patients, multiple diseases such as hypertension and diabetes are often observed. The use of injectable GCs therapy in these patients can cause an increase in blood pressure values and disrupt the internist’s previously established therapy for concomitant disease, and the same is true for glycemic values. After the use of injectable GCs, an increase in glycemic values is often observed, and it is difficult to obtain normal values in geriatric patients [45].

Based on the analysis of the above studies, one might be inclined to conclude that injection COL therapy seems to be a very good direction for the treatment of GTPS.

Study limitations

The limitations of this article include the lack of randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses on the role of injection COL therapy in GTPS. This issue requires further research on relevant patient groups, especially as the available literature on the subject is limited. In addition, the cited examples are characterized by a short follow-up period and a lack of comprehensive participation in the recommended physiotherapy.

Conclusions

Theoretical considerations and studies conducted so far seem to be encouraging for the use of injectable COL therapy, which may have a good effect in the treatment of GTPS. While the risk may be small, the lack of controlled studies and long follow-up periods prevents us from drawing definitive conclusions.