Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic systemic inflammatory disease of unknown origin, primarily characterized by inflammation of the joint’s synovial membrane, which leads to the degradation of cartilage and bone, and joint deformities. While RA primarily impacts joints, its effects can extend to other organs and body systems, highlighting its complexity and systemic nature.

Rheumatoid arthritis manifests in various ways, but the most common symptoms include pain, swelling, and stiffness in the joints, particularly worsening after periods of inactivity. Morning stiffness, which can last an hour or more, is often an early indicator of RA [1]. Additionally, RA can cause fatigue, fever, and a loss of appetite, further impacting the general health of patients. This pain and fatigue can hinder basic daily activities, and progressive joint deformities can lead to permanent disability. The disease restricts work ability and significantly reduces quality of life, increasing the risk of depression and social isolation [2].

Managing RA involves a comprehensive approach that includes pharmacological strategies to reduce disease activity and alleviate symptoms, as well as non-pharmacological measures such as physiotherapy and psychological support. The development of modern therapeutic options, particularly biological disease-modifying drugs, Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors, has significantly improved the management of RA. Despite these advancements, RA remains an incurable condition.

This paper aims to provide a thorough examination of the history of RA treatment. Reviewing the treatment history demonstrates a shift in therapeutic philosophy – from passive and symptom-relieving strategies to proactive and targeted early interventions aimed at achieving remission.

Ancient and medieval treatment strategies

In ancient and medieval times, diseases and their underlying causes were poorly understood and classified, and due to the absence of the scientific method and evidence-based medicine, treatment strategies were not adequately verified for effectiveness and safety. Methods such as various herbal therapies, bloodletting (phlebotomy), and the use of laxatives were employed. Although these practices were widely accepted and utilized, they were often ineffective and could even worsen the patients’ condition.

The 19th century: beginnings of modern rheumatology

The 19th century marked a pivotal moment in the history of medicine, characterized by significant advances in medical sciences. The first accurate description of RA was provided by the French physician Augustin Jacob Landré-Beauvais in 1800. Landré-Beauvais’ work was the first to define RA as a distinct disease, differentiating it from other forms of arthritis that had been known and described earlier [3].

The 20th century: the evolution of pharmacotherapy

Discovery of glucocorticosteroids and their impact on rheumatoid arthritis treatment

Glucocorticosteroids (GCs), discovered in the 1940s, quickly became a crucial tool in the treatment of RA. Philip Hench and his colleagues pioneered the use of cortisone, one of the first GCs, in the treatment of RA, an innovation that earned them the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1950 [4].

Glucocorticosteroids act at the cellular level by binding to cytoplasmic GCs receptors. Once activated, the receptor moves to the cell nucleus, where it regulates the expression of genes responsible for the inflammatory response, inhibiting the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines. This suppresses the inflammatory process, providing relief from symptoms such as pain and joint swelling. Oral and intra-articular administration of cortisone and hydrocortisone began in 1950–1951 [5]. Although GCs are effective in quickly controlling acute RA flare-ups, long-term use is associated with the risk of numerous serious side effects, including osteoporosis, increased susceptibility to infections, and metabolic disorders.

Currently, there is a growing consensus that GCs should be used as a bridging therapy in the treatment of RA, pending the full effect of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) [6].

Development and use of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs

Research on RA has led to a consensus that the primary goal of treating this disease is to achieve remission or low disease activity as quickly as possible. The development of DMARDs has played a crucial role in achieving this goal.

Gold salts

Gold salts, which began to be used in the treatment of RA in 1929, were among the first DMARDs [7]. This group included auranofin, aurothiosulfate, aurothiopropanol sulfonate, aurothiomalate, aurothioglucose, and sodium aurothiomalate, which reduce inflammation and disease progression. Their mechanism of action was not fully understood, but they could inhibit the activity of immune cells and cytokines [8]. With the exception of auranofin, all gold salts were administered via intramuscular injections [9]. Despite initial enthusiasm (approximately 50% of patients achieved remission), the use of gold salts has declined over the years due to potential serious side effects. Common adverse effects included abdominal discomfort, nausea, itching, skin rash, hives, proteinuria, fatal hypersensitivity reactions, kidney dysfunction, and bone marrow suppression [9]. Today, gold salts are rarely used, mainly due to the development of newer, more effective, and safer DMARDs and biological therapies.

Sulfasalazine

Originally used to treat inflammatory bowel diseases, sulfasalazine was first applied in the treatment of RA in the 1940s [10]. The mechanism of action of sulfasalazine in RA is not fully elucidated, but it is believed to have both anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects [11]. This medication is particularly useful in treating milder forms of RA, early RA, and often as part of combination therapies [10, 12, 13]. Sulfasalazine can cause side effects, such as gastrointestinal disturbances and skin reactions [12, 14]. Adverse effects usually manifest within the first 3 months of treatment [10]. Unlike many DMARDs, sulfasalazine may be suitable for pregnant women or those planning pregnancy due to its lower teratogenic risk. Combination therapy with other DMARDs, especially methotrexate (MTX), appears to be more effective than single DMARD therapy [10, 13].

Antimalarial drugs

Antimalarial drugs, such as hydroxychloroquine, were adapted for the treatment of RA in the 1950s. Their mechanism involves blocking the function of lysosomes in the antigen processing pathway, inhibiting the signaling functions of NADPH oxidase and Toll-like receptors (TLRs), reducing levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, and limiting the activation of T and B lymphocytes [15]. According to European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR) recommendations from 2022, hydroxychloroquine is regarded as a relatively weak DMARD, appropriate only for patients with early, mild RA when other conventional synthetic DMARDs are unsuitable due to contraindications or intolerance [16]. Hydroxychloroquine is generally safe for long-term use, but it has the potential to cause retinopathy. Consequently, it is recommended that patients without major risk factors undergo annual fundoscopy after five years of taking acceptable doses [17].

Methotrexate

Methotrexate was introduced into the therapy for RA in the 1980s [18]. This drug was synthesized in 1948 and was first tested in the treatment of patients with psoriasis and RA in 1951 [19]. There are many hypotheses explaining the mechanism of MTX efficacy in the treatment of RA. These include folate antagonism, adenosine signaling, polyamine inhibition, generation of reactive oxygen species, and many others. Methotrexate (amethopterin) is a structural analog of folic acid. Found in green vegetables, folic acid is converted by dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) into tetrahydrofolic acid, essential for purine and thymidine synthesis. Methotrexate binds to and deactivates DHFR, acting as an antimetabolite to prevent purine synthesis. Additionally, it blocks the conversion of glycine to serine and homocysteine to methionine, inhibiting protein synthesis. Methotrexate also inhibits the enzyme responsible for adenosine production and release, increasing adenosine levels in human fibroblast and umbilical endothelial cell cultures. Excess adenosine suppresses immune cell activity and inhibits granulocyte functions and the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (tumor necrosis factor α [TNF-α], interleukin-6 [IL-6], etc.) by monocytes [18]. Methotrexate has gained the title of the first-choice drug in the treatment of RA worldwide among DMARDs. Methotrexate is not only typically the first-line drug in RA treatment but also enhances the effect of most biological agents used as subsequent lines of treatment in RA [19]. An algorithm for treating RA patients has been developed through observations of treatment efficacy, recommending early and aggressive treatment with doses of MTX therapy (15–25 mg/week) [20]. There is some evidence that subcutaneous administration of the drug is significantly more effective than the oral administration of the same MTX dose – this approach may increase the drug’s bioavailability and minimize gastrointestinal side effects [19]. The current treatment goal should be to achieve low disease activity quickly (preferably within 3–6 months) [20]. The use of MTX may be limited due to potential side effects such as liver damage, hematopoietic disorders, and pulmonary toxicity, necessitating regular monitoring of liver and lung functions [21]. Methotrexate remains a standard in RA treatment, offering both efficacy in controlling disease activity and a relatively low side effect profile compared to other medications. Moreover, combining MTX with biologics and JAK inhibitors significantly improves clinical outcomes compared to MTX monotherapy [22].

Advances in molecular profiling, such as RNA sequencing from peripheral blood mononuclear cells, are beginning to elucidate the complex biological responses that underpin individual differences in MTX efficacy.

Leflunomide

Leflunomide (LEF) is a DMARD introduced for the treatment of RA in the 1990s. The active metabolite of LEF inhibits the enzyme dihydroorotate dehydrogenase in the pyrimidine biosynthesis pathway. This inhibition leads to a reduction in T-cell proliferation and other modifications in the immune response [23, 24]. Leflunomide remains a practical choice, particularly in mild to moderate cases. According to the latest EULAR recommendations, LEF should be considered when MTX is not suitable, with a suggested dose of 20 mg per day [16]. This recommendation underscores its established efficacy and safety profile. A systematic review by Alfaro-Lara et al. [23] comparing LEF with MTX showed that LEF is as effective as MTX in achieving ACR20 (American College of Rheumatology 20) response rates, although MTX slightly outperformed LEF in reducing the swollen joint count. Both drugs displayed similar efficacy in reducing tender joint count, physician global assessment, Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index (HAQ-DI), and serum CRP levels. Leflunomide, however, was linked to increased liver enzymes, whereas MTX caused more gastrointestinal complaints.

The most commonly reported adverse events in patients treated with LEF included diarrhea, respiratory infections, nausea, headaches, rash, increased serum hepatic aminotransferases, dyspepsia, and alopecia [24].

The role of non-pharmacological treatment and the shift towards comprehensive care

As progress was made in pharmacological treatment, the role of physiotherapy and rehabilitation in the treatment of RA also increased. Physiotherapy, focusing on improving range of motion, muscle strength, and overall functioning, has become an element of comprehensive care for patients with RA. Nonpharmacological therapy includes therapeutic patient education, physical exercises, physical modalities, orthoses, assistive devices, and balneotherapy, as well as dietary interventions [25].

The breakthrough of biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs targeting specific components of the immune system

Biological drugs are preparations produced using advanced biotechnological technologies involving living organisms or their components. Unlike traditional chemically synthesized drugs, biological drugs are usually proteins that mimic natural processes occurring in the body. Their high specificity of action and ability to interact with the immune system make them effective tools in treating autoimmune diseases.

The late 20th century brought a breakthrough in the treatment of RA with the introduction of biological DMARDs (biologic DMARDs, bDMARDs). Biological DMARDs are a group of drugs that specifically target certain components of the immune system responsible for the inflammatory process in RA. Instead of the general suppression of immunity, as is the case with traditional DMARDs, biologic disease-modifying drugs allow for a more targeted and effective approach to treatment.

In the treatment of RA, biological drugs act on various elements of the immune system by blocking key cytokines such as TNF-α or IL-1, IL-6 and modulating the activity of B and T lymphocytes. Monoclonal antibodies and fusion proteins are the most commonly used classes of biological drugs in RA therapy. The first bDMARDs were TNF-α inhibitors, introduced in the 1990s. Drugs such as infliximab (INF), etanercept (ETA), adalimumab (ADA), certolizumab pegol, and golimumab (GOL) revolutionized the treatment of RA, offering patients the possibility of significantly reducing symptoms and slowing disease progression. A summary of clinical trial findings on the efficacy and safety of bDMARDs for treating RA is presented in Table I.

Table I

Summary of clinical trial findings on the efficacy and safety of bDMARDs in RA treatment

| bDMARD | First author, year of publication, trial name, reference | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|

| INF | Maini et al. 1999, ATTRACT [57] | In a 30-week period, treatment combining INF and MTX proved to be more effective than MTX alone for patients with active RA who had not responded to MTX previously |

| Smolen et al. 2006, ASPIRE [58] | Elevated C-reactive protein levels, high erythrocyte sedimentation rate, or ongoing disease activity was linked to increased radiographic progression in patients treated with MTX alone. In contrast, patients receiving both MTX and INF showed minimal radiographic progression, regardless of the presence of these traditional predictors | |

| ETA | Genovese et al. 2002, ERA [59] | As a monotherapy, ETA was safe and more effective than MTX in reducing disease activity, preventing structural damage, and decreasing disability over a 2-year period in patients with early, aggressive RA |

| van der Heijde et al. 2006, TEMPO [60] | Over a 2-year period, combining ETA with MTX reduced disease activity, slowed radiographic progression, and improved function more effectively than either treatment alone. The combination therapy did not result in increased toxicity | |

| Emery et al. 2008, COME [61] | In patients with early severe RA, achieving both clinical remission and radiographic non-progression within 1 year is possible with combined treatment of ETA and MTX | |

| ADA | Weinblatt et al. 2003, ARMADA [62] | Adding ADA at doses of 20 mg, 40 mg, or 80 mg administered subcutaneously every other week to long-term MTX therapy in patients with active RA resulted in significant, rapid, and sustained improvement in disease activity over 24 weeks compared to MTX with placebo |

| Breedveld et al. 2006, PREMIER [63] | For patients with early, aggressive RA, combination therapy with ADA and MTX was significantly more effective than either MTX alone or ADA alone in improving disease signs and symptoms, inhibiting radiographic progression, and achieving clinical remission | |

| Furst et al. 2003, START [64] | Adding 40 mg of ADA, administered subcutaneously every other week, to standard antirheumatic therapy is well tolerated and significantly improves signs and symptoms of RA; ADA is a safe and effective option for patients with active RA who have not adequately responded to standard antirheumatic treatments, including one or more traditional DMARDs, GCs, NSAIDs, and analgesics | |

| CZP | Keystone et al. 2009, RAPID 1 [65] | Treatment with certolizumab pegol at doses of 200 or 400 mg combined with MTX led to rapid and sustained reductions in RA signs and symptoms, inhibited structural joint damage progression, and improved physical function compared to placebo plus MTX in patients with an incomplete response to MTX |

| Smolen et al. 2009, RAPID 2 [66] | Certolizumab pegol combined with MTX was more effective than placebo plus MTX, rapidly and significantly improving RA signs and symptoms, enhancing physical function, and inhibiting radiographic progression | |

| Smolen et al. 2015, CERTAIN [67] | Adding certolizumab pegol to non-biologic DMARDs is an effective treatment for RA patients with predominantly moderate disease activity, enabling the majority to achieve low disease activity or remission. However, the data suggest that certolizumab pegol cannot be withdrawn in patients who achieve remission | |

| Atsumi et al. 2016, C-OPERA [68] | In MTX-naive early RA patients with poor prognostic factors, certolizumab pegol combined with MTX significantly inhibited structural damage and reduced RA signs and symptoms | |

| Emery et al. 2017, C-EARLY [69] | Treatment with certolizumab pegol and dose-optimized MTX in DMARD-naive early RA patients resulted in significantly more patients achieving sustained remission and low disease activity, improved physical function, and inhibited structural damage compared to placebo with dose-optimized MTX | |

| GOL | Smolen et al. 2009, GO-AFTER [70] | GOL alleviated the signs and symptoms of RA in patients with active disease who had previously been treated with one or more TNF-α inhibitors |

| Emery et al. 2010, GO-BEFORE [71] | GOL alone is comparable to MTX alone in reducing RA signs and symptoms in MTX-naive patients, with no unexpected safety concerns | |

| Keystone et al. 2011, GO-FORWARD [72] | The response rates achieved by patients receiving GOL at 24 weeks were sustained through 52 weeks. The safety profile was consistent with that of other TNF-α inhibitors | |

| ABA | Genovese et al. 2005, ATTAIN [73] | ABA provided significant clinical and functional benefits for patients who had an inadequate response to anti-TNF-α therapy |

| Kremer et al. 2006, AIM [74] | ABA significantly reduced disease activity in RA patients who had an inadequate response to MTX | |

| Emery et al. 2015, AVERT [75] | ABA combined with MTX showed strong efficacy compared to MTX alone in early RA and maintained a good safety profile. The ability to achieve sustained remission after withdrawing all RA therapy suggests that ABA’s mechanism may impact underlying autoimmune processes | |

| Rech et al. 2024, ARIAA [76] | 6 months of ABA treatment reduces MRI-assessed inflammation, clinical symptoms, and the risk of developing RA in high-risk individuals. These benefits persist through a 1-year drug-free observation period | |

| TOC | Smolen et al. 2008, OPTION [77] | TOC may be an effective treatment option for patients with moderate to severe active RA |

| Nishimoto et al. 2009, STREAM [78] | TOC demonstrated sustained long-term efficacy and maintained a generally good safety profile | |

| Jones et al. 2010, AMBITION [79] | TOC monotherapy outperforms MTX monotherapy, providing rapid improvement in RA signs and symptoms and offering a favorable benefit-risk profile for patients who have not previously failed treatment with MTX or biological agents | |

| Kremer et al. 2011, LITHE [80] | TOC combined with MTX results in greater inhibition of joint damage and improvement in physical function compared to MTX alone; TOC also has a well-established safety profile | |

| Burmester et al. 2016, FUNCTION [81] | TOC is effective both in combination with MTX and as monotherapy for treating patients with early RA | |

| RTX | Cohen et al. 2006, REFLEX [82] | A single course of RTX combined with MTX significantly and meaningfully improved disease activity in patients with active, longstanding RA who had an inadequate response to one or more anti-TNF therapies |

| Mease et al. 2008, DANCER [83] | RTX, when combined with MTX, effectively improved all health-related quality of life outcomes in patients with active RA, consistent with clinical efficacy | |

| Tak et al. 2011, IMAGE [84] | Treatment with RTX combined with MTX is an effective therapy for patients with MTX-naive RA | |

| SARI | Tanaka et al. 2019, KAKEHASI [85] | In Japanese RA patients with an inadequate response to MTX, treatment with SARI in combination with MTX demonstrated sustained clinical efficacy, evidenced by significant improvements in signs, symptoms, and physical function |

| Fleischmann et al. 2017, TARGE [86] | SARI combined with conventional synthetic DMARDs improved the signs and symptoms of RA and enhanced physical function in patients who had an inadequate response or intolerance to anti-TNF agents | |

| Burmester et al. 2017, MONARCH [87] | SARI monotherapy proved superior to ADA monotherapy in improving signs, symptoms, and physical function in RA patients who could not continue MTX treatment. The safety profiles of both therapies were consistent with expected class effects |

[i] ABA – abatacept, ADA – adalimumab, bDMARDs – biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, CZP – certolizumab pegol, ETA – etanercept, GCS – glucocorticosteroids, GOL – golimumab, INF – infliximab, MTX – methotrexate, NSAIDS – nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, RA – rheumatoid arthritis, RTX – rituximab, SARI – sarilumab, TOC – tocilizumab.

Biological drugs in the treatment of RA offer a new quality of therapy, enabling more effective symptom control, slowing disease progression, and improving patients’ quality of life. Their introduction into clinical practice represents a breakthrough in RA management; however, challenges related to costs, availability, and potential side effects remain significant research areas.

Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors

Tumor necrosis factor α is a crucial pro-inflammatory cytokine central to the pathogenesis of RA. It is primarily produced by macrophages and T lymphocytes and promotes the secretion of other pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, attracting inflammatory cells to the joints. Additionally, TNF-α activates fibroblasts and osteoclasts. Activated fibroblasts overexpress cathepsins and matrix metalloproteinases, leading to cartilage and bone destruction. Activated osteoclasts contribute to synovial hyperplasia and angiogenesis [26].

Biologic DMARDs from the TNF-α inhibitor group, such as ADA, INF, ETA, GOL, and certolizumab pegol, are designed to neutralize the action of TNF-α. These drugs bind directly to TNF-α molecules, preventing them from interacting with receptors on the surface of cells, thereby blocking further pro-inflammatory signaling. As a result, the activation and recruitment of inflammatory cells are reduced, leading to a decrease in the production of other pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, thereby limiting the overall inflammatory response [26].

Consequently, TNF-α inhibitors reduce the activity of osteoclasts and the production of extracellular matrix-degrading enzymes by fibroblasts and chondrocytes, inhibiting the destructive processes in cartilage and bone. Clinical studies have shown that these drugs can significantly reduce RA symptoms such as pain, swelling, and joint stiffness, as well as improving patients’ physical function. Additionally, they can slow the radiological progression of joint damage, leading to long-term improvements in patients’ quality of life [27].

The use of TNF-α inhibitors is associated with a range of adverse effects and potential dangers. One of the most serious risks is the increased likelihood of infections, as TNF-α plays a crucial role in the body’s defense against infections. Blocking TNF-α can weaken the immune response, making patients more susceptible to bacterial, viral, and fungal infections, including severe infections such as tuberculosis. Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors may also increase the risk of developing cancers, particularly lymphomas and other hematologic malignancies. Additionally, the use of these drugs can lead to new autoimmune diseases or exacerbate existing ones, such as systemic lupus erythematosus and autoimmune inflammatory liver disease. Some patients may experience allergic reactions such as diffuse drug rash. There are also reports of worsening heart failure and the occurrence of demyelinating neurological diseases such as multiple sclerosis [28]. Therefore, the use of TNF-α inhibitors requires a careful assessment of benefits and risks and regular monitoring of patients during therapy.

21st century: advances in understanding the immunopathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis leading to targeted therapies

Increasing understanding of the immunopathogenesis mechanisms of RA has been crucial in the development of biological therapies. Studies have revealed the complexity of interactions between immune cells, cytokines, and other molecular factors contributing to inflammation and joint destruction. These discoveries have enabled the development of targeted therapies that can focus on specific pathological pathways and components of the immune system responsible for the disease.

Research on the role of interleukins in the inflammatory process led to the development and introduction of new bDMARDs – IL-6 inhibitors such as tocilizumab (TOC) and sarilumab (SARI). These drugs are used when standard treatments fail and can be administered intravenously or through subcutaneous injections. Their efficacy includes significant symptom reduction and improvements in overall functioning and quality of life for patients [29].

Interleukin-6 inhibitors

Interleukin-6 is a key pro-inflammatory cytokine playing a crucial role in the pathogenesis of RA. Produced by cells such as macrophages, T lymphocytes, and fibroblasts, IL-6 regulates immune and inflammatory responses. In RA, IL-6 stimulates the differentiation of B lymphocytes into plasma cells, and activates T lymphocytes. Additionally, it affects hepatocytes in the liver, leading to the production of acute-phase proteins such as CRP and amyloid A, and stimulates osteoclasts, causing bone resorption and joint damage. Systemic effects of IL-6 through increased synthesis of acute-phase proteins, hepcidin production, and stimulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis include anemia and fatigue [30].

Biological drugs from the IL-6 inhibitor group, such as TOC and SARI, block the action of IL-6, leading to reduced inflammation and alleviation of RA symptoms. Tocilizumab and SARI are monoclonal antibodies that bind to the IL-6 receptor (IL-6R), preventing the activation of inflammatory signaling pathways. This results in decreased production of acute-phase proteins in the liver and lower levels of CRP and other inflammatory markers. Interleukin-6 inhibitors also reduce osteoclast activity, protecting bones from resorption. Clinical studies have shown that IL-6 inhibitors can significantly reduce RA symptoms, improve patients’ physical function, and slow the progression of joint damage, leading to long-term improvements in patients’ quality of life [30, 31].

The use of IL-6 inhibitors is associated with a range of adverse effects. They increase the risk of bacterial, viral, and fungal infections, including severe infections such as pneumonia and sepsis [32, 33]. They can cause elevated liver enzymes and lipids, requiring regular monitoring of liver function and lipid profile [34, 35]. Hematological problems, including neutropenia and thrombocytopenia, increase the risk of infections and bleeding, necessitating regular blood tests [35]. Hypersensitivity reactions, including anaphylaxis, and gastrointestinal issues such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, may also occur [32]. Rarely, serious complications such as intestinal perforation can arise [36]. Local reactions at the injection site, such as pain and redness, are also possible.

T-cell co-stimulation inhibitors

Under normal conditions, the activation of T lymphocytes requires two signals. The first signal comes from the antigen presented by an antigen-presenting cell (APC) on a major histocompatibility complex molecule. The second signal, known as the co-stimulatory signal, is provided by the interaction between CD80/CD86 (cluster of differentiation 80/86) molecules on the surface of the APC and the CD28 (cluster of differentiation 28) molecule on the surface of the T lymphocyte. Both signals are essential for the full activation of T lymphocytes, which then proliferate and secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines, intensifying the inflammatory response [37].

Abatacept (ABA) is a fusion protein consisting of the extracellular domain of CTLA-4 (cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4) linked to the Fc fragment of human immunoglobulin G1. CTLA-4 naturally occurs on the surface of T lymphocytes and acts as an inhibitor of co-stimulation. Abatacept binds to the CD80/CD86 molecules on APCs, preventing them from interacting with CD28 on T lymphocytes. This way, ABA blocks the second signal necessary for T lymphocyte activation [38, 39].

Blocking co-stimulation with ABA leads to the inhibition of T lymphocyte activation, resulting in decreased proliferation of these cells and reduced secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interferon γ, IL-2, and TNF-α. Consequently, there is a reduction in the infiltration of inflammatory cells in the joints and the degree of joint tissue damage, leading to alleviation of RA symptoms such as pain, swelling, and joint stiffness [39, 40].

Abatacept is well tolerated and safe for patients with RA. Common side effects include nasopharyngitis, headache, nausea, cough, and fatigue. The rate of serious infections with ABA is similar to other treatments, with no significant issues related to kidney, liver, or blood toxicities. Infusion reactions are rare and usually involve headaches, dizziness, nausea, and vomiting. Additionally, no significant antibody response to the treatment has been detected [40].

B-cell inhibitors

B lymphocytes play a crucial role in the pathogenesis of RA by producing autoantibodies such as anti-citrullinated protein antibodies (ACPA) and rheumatoid factor (RF), which form immune complexes that trigger inflammatory reactions in the joints. They also act as APCs, activating T lymphocytes and exacerbating inflammation by secreting pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α [41].

Rituximab (RTX), a biological B cell inhibitor, is a chimeric monoclonal antibody that binds to the CD20 antigen on the surface of B lymphocytes. Upon binding to CD20, RTX induces the destruction of B lymphocytes through antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity, complement-dependent cytotoxicity, and the induction of apoptosis. The reduction in B lymphocytes leads to decreased production of autoantibodies, limited antigen presentation, and reduced secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines, resulting in diminished inflammation and alleviation of RA symptoms [42].

Clinical studies have shown that RTX is effective in reducing disease activity in RA patients, especially those who do not respond to other therapies.

However, the use of RTX in RA patients carries the risk of adverse effects. The main risk is increased susceptibility to infections due to B lymphocyte depletion. Infusion-related reactions, such as fever, chills, rash, itching, shortness of breath, and headache, are common. Rituximab can also cause hypersensitivity reactions, including rare but severe anaphylactic reactions. Hematologic problems, such as neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, and anemia, increase the risk of infections and bleeding, necessitating regular blood tests. There is also a risk of viral reactivation, such as hepatitis B virus, and rare kidney damage, especially in patients with pre-existing kidney conditions [43].

The advent of Janus kinase inhibitors as a new class of oral targeted disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs

Janus kinase inhibitors have significantly advanced the treatment of RA by providing an effective oral therapeutic alternative to bDMARDs. These low-molecular-weight compounds, which include tofacitinib (TOFA), baricitinib (BARI), upadacitinib (UPA), filgotinib (FIL), and peficitinib, block the activation of JAKs – JAK1, JAK2, JAK3 – and Tyk2, which prevents the phosphorylation of the STAT (signal transducer and activator of transcription) proteins, critical regulators of inflammatory and immune responses [44]. This targeted mechanism of action classifies JAK inhibitors as a new class of targeted synthetic DMARDs (tsDMARDS).

The specificity of each inhibitor for different JAK isoforms varies, contributing to their unique efficacy and safety profiles. For instance, UPA and FIL primarily target JAK1, which influences specific cytokines such as interferon, while peficitinib affects a broader range of cytokines.

Janus kinase inhibitors offer convenience with their oral administration and have been shown to be as effective as bDMARDs in inducing remission, controlling disease activity, and improving patient-reported outcomes in RA patients, especially those who have not responded adequately to MTX or bDMARDs [45]. A summary of clinical trial findings on the efficacy and safety of JAK inhibitors in the treatment of RA can be found in Table II.

Table II

Summary of clinical trial findings on the efficacy and safety of JAK inhibitors in RA treatment

| JAK inhibitor | Trial name | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|

| TOFA | ORAL Solo [88] | In patients with active RA, TOFA monotherapy led to significant reductions in symptoms and improvements in physical function |

| ORAL Sync [89] | Patients with active RA who received TOFA along with conventional DMARDs experienced sustained, significant, and meaningful improvements in patient-reported outcomes compared to placebo | |

| ORAL Standard [90] | For RA patients on background MTX, TOFA was significantly more effective than placebo and had similar efficacy to ADA | |

| ORAL Step [91] | In a population with an inadequate response to TNF-α inhibitors, TOFA combined with MTX resulted in rapid and meaningful improvements in RA symptoms and physical function over 6 months, with manageable safety | |

| UPA | SELECT-NEXT [92] | Patients with moderately to severely active RA treated with UPA (15 mg or 30 mg) in combination with conventional synthetic DMARDs exhibited significant improvements in clinical signs and symptoms |

| SELECT-MONOTHERAPY [93] | UPA monotherapy showed significant improvements in clinical and functional outcomes compared to continued MTX in MTX inadequate-responder patients, with a safety profile similar to earlier studies | |

| SELECT-BEYOND [94] | UPA (15 mg or 30 mg) significantly improved various aspects of quality of life in patients with inadequate responses to bDMARDs, with a greater number of patients achieving clinically meaningful improvements compared to placebo | |

| BARI | RA-BEGIN [95] | BARI, either alone or combined with MTX, showed better efficacy and acceptable safety compared to MTX alone as initial treatment for active RA |

| RA-BEAM [96] | For RA patients with an inadequate response to MTX, BARI significantly improved clinical outcomes compared to both placebo and ADA | |

| RA-BUILD [97] | In RA patients with an inadequate response or intolerance to conventional synthetic DMARDs, BARI resulted in clinical improvement and slowed progression of radiographic joint damage | |

| FIL | FINCH 1 [98] | FIL significantly improved RA signs and symptoms and physical function, and inhibited radiographic progression in patients with inadequate response to MTX; FIL was non-inferior to ADA and well tolerated |

| FINCH 2 [99] | For patients with moderate to severe RA who were refractory to biologic DMARDs, FIL (100 mg or 200 mg) led to a significantly greater clinical response at week 12 compared to placebo. Further research is needed to assess long-term efficacy and safety | |

| FINCH 3 [100] | FIL in combination with MTX or as monotherapy significantly improved signs, symptoms, and physical function in patients with limited or no prior MTX exposure. However, FIL monotherapy did not achieve a superior ACR20 response rate compared to MTX; FIL was well tolerated and had an acceptable safety profile compared to MTX |

However, despite these benefits, the use of JAK inhibitors requires careful consideration due to potential adverse effects. These can include serious infections, liver and kidney function impairment, and possible hematological issues. Research indicates that JAK inhibitors are associated with a higher risk of MACE (major adverse cardiovascular events) and malignancy compared to TNF inhibitors, however, this phenomenon is not observed with placebo or MTX. Tumors are rare occurrences in all comparisons [46]. The risk of these events necessitates judicious use and careful monitoring during treatment [44].

The European Medicines Agency’s Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee (PRAC) has issued new guidelines for the use of JAK inhibitors aimed at minimizing the risk of serious side effects associated with their use. These guidelines address concerns related to cardiovascular diseases, thrombosis, cancer, and serious infections. They are specifically directed at risk groups, such as individuals over 65 years of age, patients at increased risk of cardiovascular problems, current or former smokers, and those at a higher risk of developing cancer. The committee recommends using JAK inhibitors only when other therapies are not available. The new guidelines are based on study findings, including data from clinical trials on TOFA and observational studies on BARI [47].

Overall, JAK inhibitors have become an integral component of modern RA management strategies, recommended as first-line treatments in cases where traditional therapies fail. Their development and application are poised to continue evolving with ongoing research aiming to optimize their use through precision medicine approaches, potentially enhancing their effectiveness and safety profile for individual patients [45].

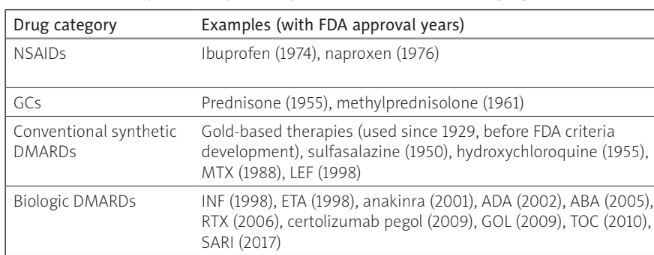

A summary of the pharmacological treatment options for RA is presented in Table III.

Table III

Summary of therapeutic options available for managing RA

[i] ABA – abatacept, ADA – adalimumab, DMARDs – disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, ETA – etanercept, FDA – Food and Drug Administration, FIL – filgotinib, GCs – glucocorticosteroids, GOL – golimumab, INF – infliximab, JAK – Janus kinase, NSAIDs – nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, RA – rheumatoid arthritis, RTX – rituximab, SARI – sarilumab, TOC – tocilizumab, TOFA – tofacitinib, UPA – upadacitinib.

The role of biomarkers in predicting treatment response and personalizing therapy

The development of biomarkers has been a key step toward the personalization of RA treatment. Biomarkers such as ACPA and RF help in diagnosing the disease and can also be used to predict responses to specific therapies. Advances in genetics and genomics pave the way for identifying genetic markers associated with RA, which may enable an even more personalized treatment approach tailored to an individual’s risk profile and predicted therapy response. New markers are emerging that may be useful in diagnosing and monitoring the disease, such as anti-pentraxin 3 (anti-PTX3) and anti-dual specificity phosphatase 11 (anti-DUSP11) autoantibodies – biomarkers for the diagnosis of ACPA-negative RA [48]. Anti-carbamylated protein (anti-CarP) antibodies, similarly to ACPA and IgM-RF, can be detected in healthy individuals before developing RA, with anti-CarP antibodies and ACPA appearing years prior to the RA diagnosis, often earlier than IgM-RF [49]. Antibodies against heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins – anti-hnRNP A2/B1 (RA33) – which interact with pre-mRNA, are another potential biomarker in RA, though further research is needed [50].

Recent advancements in stem cell therapy

Therapies utilizing stem cells have emerged as a promising direction in the treatment of RA. Although research in this area is still in its early stages, preliminary results are promising, suggesting the potential ability of stem cells to promote joint tissue regeneration and modulate the immune response [51].

The impact of digital health technologies on managing rheumatoid arthritis

Digital technologies, including telemedicine, mobile applications, and wearable monitoring devices, have revolutionized the treatment of RA. These technologies enable monitoring of disease progression and treatment effects in real time. Digital self-monitoring tools help patients manage pain, physical activity, and medication adherence, while telemedicine platforms provide easier access to specialist care. Advances in big data and artificial intelligence open new possibilities for analyzing health data, which can lead to a better understanding of RA and more effective treatment strategies [52].

Ongoing research in gene therapy and novel immunomodulatory strategies

New treatment methods are developing, including cellular therapies such as treatments based on mesenchymal stem cells and therapies utilizing tolerogenic dendritic cells, as well as the use of natural substances, e.g. cannabinoid drugs. Research on gene therapy and new immunomodulatory strategies is opening new perspectives for future RA treatments. Gene therapy, aimed at modifying the expression of genes responsible for the inflammatory process, is being investigated as a potential long-term solution for RA [53]. Several modern technologies also offer new possibilities for treating RA. Proteolysis targeting chimera (PROTAC) technology enables targeted degradation of pathogenic proteins, effectively eliminating proteins that cause joint inflammation [54]. Nanoparticles allow for precise delivery of drugs directly to affected joints, minimizing side effects and increasing treatment efficacy [55]. CRISPR-Cas9 technology enables precise gene editing, correcting mutations or silencing pro-inflammatory genes, which can lead to long-term control or even a cure for RA [56]. These methods have the potential to revolutionize RA treatment by offering more personalized and effective therapies.

Current challenges and future directions

Despite significant progress in the treatment of RA, there are still limitations and unmet needs. Current therapies, including DMARDs, bDMARDs, and tsDMARDs are not effective for all patients, and some may experience unacceptable side effects. Additionally, there is a clear need for better control over the long-term effects of RA, including bone erosion and the risk of comorbidities such as heart disease. In the context of future research, it will also be important to focus on the personalization of therapy, which means tailoring treatment approaches to the individual needs of the patient. The development of precision medicine in RA could lead to more effective and safer therapies, minimizing side effects and improving the quality of life for patients.

Conclusions

The treatment of RA has evolved dramatically, transitioning from ancient, empirical methods to sophisticated, targeted therapies. The 19th century’s scientific advancements led to the recognition of RA as a distinct disease. The 20th century introduced GCs, which, despite their efficacy, highlighted the need for more sustainable solutions due to their long-term side effects. The development of DMARDs, particularly MTX, marked significant progress in controlling disease progression.

The introduction of bDMARDs and JAK inhibitors revolutionized RA treatment. The integration of biomarkers for personalized therapy has further refined treatment strategies. Future advancements in gene therapy, and digital health technologies hold promise for further improving RA management. Despite these advances, challenges such as ensuring equitable access to therapies and addressing the needs of patients who do not respond to current treatments persist. The ongoing focus on personalized medicine and the development of safer, more effective therapies will be crucial in overcoming these challenges and enhancing patient outcomes.