Introduction

Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) in young adults (aged ≤ 35 years), although relatively rare, almost always represents a diagnostic challenge as young patients, as compared with older ones, have broader etiology, other cardiovascular risk factors, and different clinical manifestations and outcomes [1, 2]. Although early atheromatous coronary artery disease remains one of the major causes of ACS in a young population [3], other important etiologies comprise non-atheromatous coronary artery disease (congenital coronary anomalies, small and medium vessel vasculitides/vasculitic syndromes, spontaneous dissections, myocardial bridging), hypercoagulable states (antiphospholipid syndrome – APLS, factor V Leiden mutation and other thrombophilias), substance abuse (recreational drug use, particularly cocaine and amphetamines, alcohol binge drinking) [4, 5].

In this context, patients with rheumatologic disorders represent a special risk group [6], typically combining multiple risk factors (vasculitis, secondary APLS [7], early [8] and accelerated [9] development of atheromatous lesions). The risk of coronary involvement in rheumatologic diseases depends on the clinical entity of the latter. For instance, in rheumatoid arthritis (RA), which is one of the most prevalent inflammatory rheumatologic disorders, as well as in ankylosing spondyloarthritis, it is relatively low as compared with primary systemic vasculitides or systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) [10].

Case report

A 26-year-old man presented in October 2016 to our rheumatology clinic because of non-erosive polyarthritis with severely elevated acute phase reactants (erythrocyte sedimentation rate 73 mm/h, reference value: < 15 mm/h; C-reactive protein 25 mg/l, reference value: < 5 mg/l). This was preceded by a 2-year history of follow-up outside our clinic for “rheumatoid arthritis” (Table I), as well as a recent acute coronary syndrome (presumably, a myocardial infarction) (Fig. 1) due to multivessel coronary artery disease (Figs. 2 and 3) managed with coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG). At the surgeon’s discretion, it was decided to use venous grafts, and not the left internal mammary artery, as the latter showed decreased pulsation (retrospectively this was attributed to manifestation of vasculitis). The patient’s height was 170 cm, weight 55 kg, giving him a body mass index of 19 kg/m2.

Table I

Timeline

| Time | Events |

|---|---|

| Late 2014 | The patient first experienced pain in knee joints |

| Early 2015 | The patient started experiencing morning joint stiffness, swollen hands, dyspnea, gradual weight loss (~15 kg within 1 year). Rheumatoid arthritis was suspected and the patient initiated non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug treatment with a positive effect |

| January 2016 | Hospitalization due to severe anemia |

| February 2016 | The patient was experiencing persistent arthralgias, subfebrile body temperature, and hair loss. Continuous therapy with corticosteroids and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs was initiated |

| 1–2 March 2016 | Repeated attacks of substernal chest pain at rest radiating to both arms, accompanied by fatigue and diaphoresis. The patient did not seek medical care |

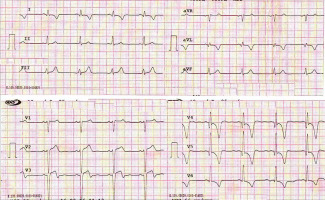

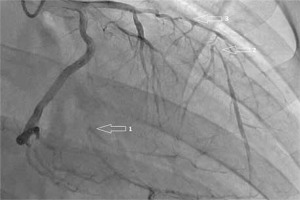

| 3 March 2016 | The patient presented to a local hospital. His ECG revealed T-wave inversion in anterior chest leads (Fig. 1), echocardiography demonstrated multiple segmental wall motion abnormalities with depressed systolic function (LVEF 35%), and coronary angiography detected a multivessel coronary artery disease (Fig. 2). The patient was medically stabilized |

| 17 March 2016 | Coronary artery bypass grafting: SVG-OM, SVG-LAD, SVG-DA |

| October 2016 | The diagnosis of “rheumatoid arthritis” was revised in favor of “systemic lupus erythematosus” |

| February 2019 | Last follow-up. The patient is being followed up yearly in an outpatient clinic. His left ventricular systolic function has improved (LVEF 50%). The patient is receiving DMARDs and has been in remission for the past 2 years |

Fig. 1

Twelve-lead electrocardiogram demonstrating ST-elevation and deep inverted T-waves in anterior chest leads consistent with recent myocardial infarction.

Fig. 2

Right anterior oblique view of the left coronary artery showing occluded (1) first obtuse marginal artery and (2) left anterior descending artery with retrograde collateral supply, and (3) critical stenosis of the diagonal branch.

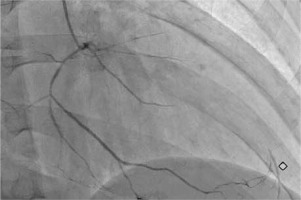

Fig. 3

Right anterior oblique view of the right coronary artery showing a diffusely narrowed right coronary artery providing collateral supply to distal left anterior descending artery.

The described patient did not have any classical cardiovascular risk factors. Additional laboratory investigation showed the presence of anemia, leukopenia 3,000/μl, lymphopenia 1,000/μl, thrombocytopenia 140 K/μl, negative rheumatoid factor (< 10 IU/ml, reference value: < 14 IU/ml), negative A-CCP IgG (< 7 IU/ml, reference value: < 17 IU/ml), positive antinuclear antibodies test (ANA AAB 4.7 IU/ml, reference value: < 1 IU/ml), positive anti-double stranded DNA test (ANA-dsDNA IgG 38 IU/ml, reference value: < 14 IU/ml), positive anticardiolipin antibodies (IgA 3.12 IU/ml, reference value: < 1 IU/ml; IgG 4.28 IU/ml, reference value: < 1 IU/ml; IgM 8.07 IU/ml, reference value: < 1 IU/ml), positive extractable nuclear antigen antibodies (ENA AAB 2.9 IU/ml, reference value: < 1 IU/ml), positive anti-SSA (Ro) 1 : 100 (reference value: < 1 : 50), anti-SSB (La) 1 : 100 (reference value: < 1:50). Detailed history taking revealed the fact of photosensitivity.

Thus, the patient met the classification criteria for SLE according to the 1997 Update of the 1982 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) Revised Criteria [11] by having 5 criteria (photosensitivity, polyarthritis, hematologic disorders, immunologic disorders, positive antinuclear antibodies) while ≥ 4 criteria are required for the diagnosis.

He also met the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics (SLICC) [12] classification criteria by having 6 criteria (clinical criteria: photosensitivity, synovitis in ≥ 2 joints, leukopenia; immunologic criteria: positive ANA, anti-DNA, antiphospholipid antibodies) while ≥ 4 criteria, including at least 1 clinical and 1 laboratory criterion, are required. The patient also scored 23 points according to the new ACR/EULAR (European League Against Rheumatism) classification criteria for SLE [13] (Table II). Systemic lupus erythematosus activity index (SLEDAI) score was 18 (arthritis = 4, increased DNA binding = 2, thrombocytopenia = 1, leukopenia = 1, alopecia = 2, vasculitis = 8). This necessitated reassessment of the previous diagnosis of RA, and diagnosis of the patient with SLE and secondary APLS.

Table II

New 2018 ACR and EULAR criteria for classification of systemic lupus erythematosus [13]

Patient management and follow-up

The diagnosis of SLE and subsequent administration of disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs, including hydroxychloroquine, systemic glucocorticoids and methotrexate according to current recommendations [14] along with anticoagulation with warfarin and low-dose acetyl salicylic acid, resulted in drug-induced remission (SLEDAI score 2 [alopecia]) and freedom from major adverse cardiac events that has been maintained for the past 2 years. According to our judgment, previous therapy which the patient was receiving for RA was limited by the presence of anemia, and therefore adequate reduction of the disease activity at that time was not achieved.

Discussion

Systemic lupus erythematosus is a chronic autoimmune disease characterized by multisystem involvement. Any part of the heart may be affected, manifesting as myocarditis, pericarditis, conduction defects, valvular disease, or coronary thrombosis. Some patients also develop pulmonary hypertension. The pathogenesis of these variable manifestations is complex and still not completely understood [6, 15, 16]. With regard to the coronary artery disease, most of the available literature sources either focus on atherosclerotic process or do not contain information on the nature of coronary involvement [8, 9, 17].

Although traditional cardiovascular risk factors do not fully explain the increased cardiovascular risk in SLE, the elevated risk of ACS in these patients is considered to be associated with obesity, dyslipidemia, arterial hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, sedentary lifestyle, male gender, smoking, advanced age, hyperhomocysteinemia, renal dysfunction, family history of coronary heart disease, as well as with the disease activity and presence of antiphospholipid antibodies. Antiphospholipid syndrome is associated with the incidence of myocardial infarction and angina pectoris of 5.5% and 2.7%, respectively, and the incidence of coronary heart disease is relatively not high if compared with the incidence of cerebral and/or deep vein thromboses [18]. Acute coronary syndrome is an important complication in young patients with primary APLS without coronary heart disease risk factors, as well as in patients with SLE and secondary APLS. In some patients ACS/myocardial infarction developed before or shortly after the diagnosis of SLE [19, 20].

The relative roles of coronary thrombosis and of coronary atherosclerosis in patients with APLS and/or SLE have not yet been thoroughly studied [21]. On the other hand, the issue of percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI) and CABG in patients with SLE and ACS needs further assessment because of equivocal data with regard to their appropriateness and effectiveness and increased associated risks [22].

The present case report highlights the difficulty of diagnosing SLE in a 26-year-old man who had been followed up by different specialists with a working diagnosis of seronegative “rheumatoid arthritis”. Following the ACS, the patient’s history and laboratory findings required a further detailed analysis. Attention was drawn by significant hematologic disorders (anemia, leukopenia, lymphopenia, thrombocytopenia) and a history of photosensitivity. The first manifestation of SLE in this patient was persistent non-erosive polyarthritis with highly elevated acute phase reactants, and subsequently vasculitis (coronaritis) caused symptomatic multivessel coronary artery involvement requiring CABG.

From another standpoint, the patient did meet the ACR classification criteria for RA [23] (Table III). However, no consideration was given to alternative causes of arthritis in the light of hematological manifestations and a history of photosensitivity. Also, this case serves an example that especially in seronegative arthritis, which may formally fit the classification criteria of RA, the diagnosis of RA should be supported by imaging studies. Although younger age at disease onset and short disease duration have been associated with non-erosive RA in large cohort studies [24], a non-erosive disease associated with other extra-articular symptoms should raise the suspicion of SLE [25].

Table III

2010 ACR/EULAR classification criteria for rheumatoid arthritis [23]

[i] RF – rheumatoid factor, ACPA – anti-citrullinated protein antibodies, CRR – C-reactive protein, ESR – erythrocyte sedimentation rate. The criteria marked in bold were detected in the patient. 2010 ACR/EULAR score ≥ 6 = definite rheumatoid arthritis; patient’s score = 7, leading to misclassification of the patient.

Indeed, rheumatic diseases are frequently characterized by multiple and variable manifestations, and classification criteria of these disorders have been primarily developed to identify homogeneous cohorts for clinical research [26]. Although the classification criteria are widely used in routine clinical practice for diagnostic purposes, the clinical diagnosis of many rheumatic diseases with multisystem involvement, including SLE, is still largely at the discretion of the attending physician.

The present case has some limitation because the diagnosis of coronary vasculitis was made based only on the clinical presentation without histopathological examination of the affected vessel being performed. Therefore, one cannot rule out another background of coronary artery involvement, e.g., APLS and premature accelerated atherosclerosis.

Conclusions

The present case illustrates how early onset of ACS and subsequently multivessel coronary artery disease led to revision of the previous diagnosis of concomitant RA, and finally allowed the diagnosis of SLE to be established. In young patients with ACS and without any classical cardiovascular risk factors, another underlying etiology of vessel involvement such as systemic connective tissue disease should be considered. In such cases the indications for interventional strategy should be carefully discussed in terms of risks and benefits. If early RA is diagnosed according to classification criteria, other causes of arthritis should be excluded in patients with extra-articular manifestations (i.e., leukopenia, lymphopenia, thrombocytopenia, anemia).