Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is considered one of the most common disabling joint disorders [1]. In OA all joints can be affected; however, knee joints are more frequently subjected to weight-bearing activities and are particularly prone to degenerative changes (27%) [2]. Pathophysiological changes in knee OA (KOA) are degeneration of the articular cartilage, changes in the subchondral bone structure, synovial inflammatory cell infiltration, and secondary osteophyte formation [3]. These changes result in joint pain, swelling, deformity, and disability [4]. Due to continuous pain and stiffness, most OA patients are subjected to repeated falls and face mental health issues such as depression and anxiety as well as impaired quality of life [5]. In addition, patients with OA impose a substantial economic burden on society [6].

Depression can exacerbate physical symptoms and can lead to a reduction in patients’ adherence to prescribed drugs [7]. Depression is often accompanied by anxiety and stress [8]. Researchers found that anxiety disorders can occur up to 11 years before depressive disorders [9], and so it is not surprising that the two diseases frequently co-exist [10]. It has been reported that 40% of lower limb OA patients were burdened with clinically significant anxiety or depression – at least 2.5 times greater than expected in the general population [11]. The variability in symptoms and response to treatment among OA patients cannot be explained by the disease pathology alone. Anxiety or depression may cause physical and cognitive changes and may be involved in hindering an individual’s functional capacity [12]. Mental health, pain, and disability are closely interconnected, and a multidisciplinary approach should be encouraged in the management of OA [11].

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) is a widely used tool for assessing mental health [13], to determine the prevalence of anxiety and depression in non-psychiatric hospital clinic patients [14]. The HADS questionnaire has been translated into numerous languages, and validation studies for several of these translations are available, which verifies the questionnaire’s international applicability [15]. The brief self-report scale is presented to patients in about 5–10 minutes and scored in about a minute, so it is considered as a valuable screening instrument for evaluating dimensional representation of mood [14].

Although numerous studies have addressed the impact of OA disorder on physical status, OA implications for mental health still need to be more deeply investigated. The present study aimed to screen for anxiety and depression among patients with primary KOA, and to study the relationship between HADS score and different disease parameters.

Material and methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted on 50 patients (29 females and 21 males) fulfilling classification criteria for primary KOA [16]. All patients were recruited from the Rheumatology and Rehabilitation Clinic, Kasr Al-Ainy University Hospitals. Exclusion criteria included patients having secondary KOA patients, below 40 years of age, and patients with established diagnosis of connective tissue disease. Fifty age- and sex-matched volunteers were included as a control group.

Medical history was taken from KOA patients and a clinical examination was conducted, including general examination, body mass index (BMI) calculation [17] and musculoskeletal examination (knee joint examination and examination of lower limb-related joints). Patient assessment of pain was performed using the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) for pain intensity. This scale is most commonly anchored by “no pain” (score of 0) and “worst imaginable pain” or “pain as bad as it could be” (score of 10) [10-mm scale] [18]. Functional status assessment was evaluated using the 6-minute walk test (6MWT) [19]. Plain X-ray both knees standing A-P view was performed in all patients and scored according to the Kellgren and Lawrence system [20].

The HADS questionnaire was completed by all the participants. It has two subscales for anxiety (HADS-A) and depression (HADS-D), with seven items each. Each item has scores ranging from 0 to 3. A total subscale score of 0 on either anxiety or depression subscales means there is no anxiety or depression, and 21 is the maximum possible score, meaning the most severe anxiety or depression. Summing the scores of anxiety and depression scales reflects a score of emotional distress with 0 meaning no distress, and 42 meaning the highest possible level of emotional distress. Cutoff scores are 0–7 for non-cases; 8–10 for borderline/mild cases; 11–21 for definite/severe cases; with a score of 11 or more indicating “potential psychiatric caseness” [21]. The HADS has shown satisfactory psychometric properties in different patient groups as well as in general populations [22]. The Arabic version of HADS was used and explained to all participants [23].

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using the program IBM SPSS Statistics version 21. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to test for distribution normality. Quantitative data were summarized using the arithmetic mean and standard deviation for parametric data, the median and range for non-parametric data, and frequencies were used for qualitative data. The χ2 test was performed to compare categorical data. Fisher’s exact test was used if cell count < 5. The independent t-test was used for comparative analysis of normally distributed quantitative data between 2 groups. The one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test was used to compare between quantitative data in more than 2 groups. Pearson correlation was used to compare normally distributed quantitative data, while Spearman’s correlation coefficient was used for non-normally distributed data. Stepwise linear regression analysis was performed. Results were considered significant if the p-value < 0.05.

Results

Out of the 50 primary KOA patients, 48% of patients were female and 42% were male, while in the control group 50% were female and 50% male. Mean age of the patients was 57 ±9 years, while mean age of the control group was 53 ±6 years. Sex and age were comparable between patients and controls (p > 0.05), and the mean disease duration was 5.17 ±5.5 years. Married patients made up 76%, while 24% were formerly married, and 18% of KOA patients were cigarette smokers. Mean body mass index in KOA patients was 30.5 ±6.5, while in controls it was 28.8 ±2.6 (p = 0.09). Family history of KOA was found in 32% of patients. Clinical characteristics in primary KOA patients, functional assessment, radiographic assessment, co-morbidities and treatment received by patients are presented in Table I. The mean HADS score was statistically significantly higher in the KOA patient group than controls (p = 0.001). The mean HADS-A score was significantly higher in KOA patients than controls (p < 0.001). Regarding HADS-A categories, anxiety was significantly more frequent in patients (44%) than in controls (10%) (p < 0.001). Although depression was higher in KOA patients (32%) than controls (14%), no significant difference was found between HADS-D categories (Table II).

Table I

Disease characteristics in KOA patients

Table II

Comparison of patients and control group according to mean Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale scores, mean Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale A (Anxiety) scores and mean Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale D (Depression) grades

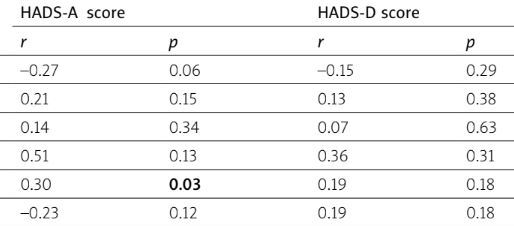

Females had higher mean HADS-A and HADS-D scores than males, and the difference was statistically significant (p = 0.001, p = 0.03). No significant difference was found between HADS-A and HADS-D scores based on age groups (45–60 vs. 61–80 years), marital status, smoking, family history of KOA, hypertension or diabetes mellitus (Table III). Patients with each of the manifestations inactivity stiffness, knee giving way, locking of the knees, and crepitus had significantly higher mean HADS-A scores in comparison with those without (p = 0.02, p = 0.003, p = 0.002, p = 0.007), respectively. HADS-D scores were significantly higher in KOA patients who suffered from a limited range of knee joint motion (p = 0.04). The mean HADS-A score was non-significantly worse in patients with abnormal functional assessment (knee pain hindering movement < 6 minutes; p = 0.052). No significant difference was found regarding HADS-A scores in relation to each of symmetrical knee involvement, anserine bursitis, knee effusion, limited ROM, knee joint deformity or abnormal functional capacity. Moreover, comparing HADS-D scores between KOA patients who had inactivity stiffness, symmetrical knee involvement, giving way at the knees, crepitus, anserine bursitis, knee effusion, knee joint deformity or abnormal functional capacity revealed no statistically significant difference (Table IV). There was a significant positive correlation between HADS-A scores and duration of inactivity stiffness (p = 0.017). No significant correlation was found between HADS-A score and any of the following disease parameters: age, BMI, disease duration, intensity of pain using VAS, functional capacity. Similarly, the correlation between HADS-D score and each of age, BMI, disease duration, intensity of pain, duration of inactivity stiffness, and functional capacity was non-significant (Table V). HADS-A and HADS-D scores were comparable as regards radiological grades (p > 0.05). Knee OA patients who received intra-articular injections had significantly lower scores of HADS-D (p = 0.01) (Table VI). In regression analysis, female sex could be considered as a predictor for each of HADS-A and HADS-D (β: 0.4, 0.3, t: 3.28, 2.2, p = 0.002, 0.03, CI: 1.3–5.6, 0.2–4.4) respectively, while knees giving way was considered as a predictor for HADS-A (β: 0.34, t: 2.8, p = 0.007, CI: 0.96–5.87).

Table III

Comparison between mean Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale scores based on demographic data and general characteristics

Table IV

Comparison between mean Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale A and D scores according to the presence or absence of clinical manifestations

Table V

Correlation between anxiety and depression scores and disease parameters

Table VI

Comparison of HADS-A and HADS-D scores between KOA patients based on radiological grades and treatment received (n = 50)

Discussion

Inconsistent results regarding anxiety and depression in various autoimmune and musculoskeletal diseases have been disclosed. Pain, disability, discrimination, fear of mortality, and social stress were suggested to be among the factors involved in anxiety and depression [24]. It has been postulated that chronic elevation of inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor were involved in increased depression risk [25]. Varied prevalence rates of anxiety and depression in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients have been reported as 21–70%, and 17.6–66.2% respectively, and anxiety has been reported to be more frequent than depression in patients with RA [26]. Osteoarthritis is considered as one of the most important causes of pain, disability and economic loss in different populations [27]. The chronic pain caused by OA increases the risk of emergence of anxiety and depressive disorders among patients [28]. The HADS test has been suggested as a useful research tool to screen for the presence of anxiety and depression because it is a multi-valued scale and not just a “yes/no” clinical diagnosis as suggested [29].

In the present study, both the mean HADS overall and HADS-A scores were significantly higher in KOA patients than controls. Abnormal HADS was significantly more frequent in KOA patients than controls. It is in accordance with previous studies, as OA patients revealed higher HADS scores in comparison to controls [11, 30, 31]. Moreover, the authors of a study concluded that depressive and anxiety disorders were important issues in OA, and considered HADS score as a possible screening tool to detect these early symptoms in OA patients [32]. Other tools for mental health assessment have been used in various previous studies on OA patients. They include a study that used Symptom Checklist-90-Revised (SCL-90-R), whose authors found that 50% of the patients had depression and 43.6% had anxiety with overlapping between both of them in some patients [33]. Park et al. [34] noted higher levels of anxiety and depression as determined using subscales of the EuroQol five-dimension (EQ-5D) in KOA patients.

In contrast, a previous study carried out by Husnain et al. [35] using a HADS test did not establish an association between degenerative joint disease on one hand and depression and anxiety on the other hand, and this could be explained by the difference in duration of symptoms in their study, with a mean of 3.26 months compared to 5.17 ±5.50 years in the current study.

In the current study, females had significantly higher mean HADS-A and HADS-D scores than males, and in the regression analysis female sex was identified as a predictor for each of anxiety and depression. Similarly, Duarte et al. [36] stated that older OA females were more liable to anxiety and depression besides social isolation. In disagreement, Rosemann et al. [37] used Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) and found that 19.76% of male patients had depression, a slightly higher frequency than females, 19.16%.

In this study, although non-significant, a positive correlation was found between each of HADS-A and HADS-D scores and intensity of pain according to VAS. Prado et al. [38] stated that sufficient pain control in the presence of psychological issues could not help improve the ability to perform activities of daily living. Kroenke et al. [39] evaluated the relation between pain as measured by the Brief Pain Inventory score (BPI) and depression assessed by PHQ-9. The authors considered pain as a predictor for depression, and they highlighted that the close anatomical relation between nociceptive and affective pathways was well recognized, besides the role of each of norepinephrine and serotonin in both mood pathophysiology and pain gate control mechanisms. The difference between levels of significance between results can be attributed to sample size variation and different assessment parameters.

In the current study, giving way of the knee could be considered as a predictor for HADS-A scores. Meanwhile, some authors considered knee swelling as a predictor for anxiety in KOA patients [40]. It is noteworthy that HADS-A scores were non-significantly higher in KOA patients who had restricted functional capacity in this study. In support, Alabajos-Cea et al. [41] documented that more intense anxiety and depression were associated with more reduced functional capacity even in early KOA patients. In support of the lack of significant association between HADS-A and HADS-D scores, and grading of radiographic osteoarthritic changes, a previous study found that OA severity determined by radiological score was not a reliable predictor for either anxiety or depression [29]. Conversely, Rathbun et al. [42] documented a significant effect of depressive symptoms on KOA patients who had radiographic progression.

Knee OA patients who received either medical treatment or intra-articular injections had comparable HADS-A and HADS-D scores. On the other hand, García-López et al. [43] found that OA patients who used analgesics to help reduce their severe pain had worse limitation scores.

As poor outcomes have been reported to be significantly related to anxiety and depression in OA patients despite both conservative treatment and surgical management, a number of different self-care anxiety and depression management programs, telephone support programs, video information support programs, and new drug treatments have been tried, with varied success. Interventions to manage anxiety and depression as important comorbidities of OA disease need to be standardized [12].

Study limitations

The strengths of the current study included analysis of clinical manifestations in relation to anxiety and depression in KOA patients, whereas the number of patients and controls is among the limitations of this study. Conducting the research on a larger study population would be more informative and confirm the importance of taking into consideration mental health aspects in primary KOA patients, while highlighting the relation of the HADS test to injections received by patients. Collaboration with the psychiatry department is recommended for management and follow-up of the anxiety and depression aspects.

Conclusions

From the results of the present study we conclude that anxiety level rather than depression was significantly higher in patients with primary KOA than in controls. Female sex could be considered as a predictor for each of HADS-A and HADS-D, while knee giving way was identified as a predictor for HADS-A.