Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is an autoimmune illness mainly affecting joints, leading to joint deformity and subsequent disability [1]. Women are more affected by RA than men, with a ratio of 3 : 1 [2]. The pathogenesis of RA is believed to be regulated through a complex interaction of elements involving genetic predisposition, environmental impacts, and immunological factors [3]. A meta-analysis of population-based studies showed that the prevalence of RA ranged from 51 to 56 per 10,000 [4]. In 2010, the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) and European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR) classification criteria for RA were established, including arthritis, acute-phase reactants such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP), autoantibody positivity such as rheumatoid factor (RF) and anti-citrullinated protein antibodies (ACPA), and the duration of symptoms [5]. Despite the everyday use of RF and ACPA for diagnosing RA, their specificity is not optimal, particularly in early disease [6].

Progressive joint damage and disability are major health insults in RA patients, so preventing the progression of joint damage is essential to maintain adequate function [7]. Therefore, assessing disease activity is vital for adequate follow-up and adjustment of the therapeutic plan in RA patients [8]. One of the methods for measuring disease activity in RA patients is the Disease Activity Score in 28 joints (DAS28), which involves the CRP and ESR as acute phase reactants. However, it should be noted that these markers are not specific to RA and serve as general markers of inflammation [9]. Therefore, novel biomarkers and autoantibodies that offer greater specificity for tracking therapy response and predicting disease progression should be investigated and identified [10].

Cystatin D is a member of the endogenous cystatin family II. It is a known suppressor for cathepsins and other secretory cysteine proteases. Cathepsins H, L, and S are inhibited by cystatin D [11–13]. Cathepsin S is released into the cartilage matrix and may contribute to a detrimental inflammatory process in RA [14]. Few studies have focused on the role of cystatin D in RA, and to our knowledge, our study is the first to shed light on its relation to radiological progression in RA patients. Our study was carried out to determine the value of cystatin D in RA patients and to explore the relation between cystatin D serum level and disease activity and joint damage.

Material and methods

Patient selection

Seventy RA patients from the Department of Rheumatology and Rehabilitation of Sohag University participated in this study. The participants were diagnosed with RA if they met the 2010 ACR/EULAR criteria [15]. In addition, 40 healthy subjects with matched age and sex were enrolled as controls. Patients were excluded from the study if they had a shorter disease duration than 6 months, any autoimmune disorder other than RA, other systemic diseases, cancer, or pregnancy.

Clinical assessment

Patients’ demographic, clinical, and rheumatological data, as well as treatment regimens, were collected. Disease Activity Score in 28 joints was used to measure disease activity, and it included the Visual Analogue Scale, which allowed the patients to rate their discomfort on a scale from 0 (no pain) to 100 (the most severe pain imaginable), in addition to counting both tender and swollen joints and measuring the ESR. The patients were categorized according to DAS28 into remission (DAS28 < 2.6), mild disease activity (DAS28 between 2.6 and 3.2), moderate disease activity (DAS28 between 3.2 and 5.1), and high disease activity (DAS28 > 5.1) [16].

Laboratory assessment

The following routine laboratory parameters were measured: complete blood count was determined using a Siemens Hematology System (Siemens Healthineers, Germany), and the ESR was determined using Westergren tubes. A latex agglutination test was used to determine CRP and RF. The Cobas C 311 Chemistry Analyzer System was used to assess serum creatinine, alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, and ACPA. Human cystatin D ELISA kit, cat no. ab314723, was used for quantitative measurement of serum cystatin D according to the manufacturing protocol using the ELISA Thermo Fisher Scientific Multiscan Ex Microplate Reader, OY, FI-01621, Vanta, Finland.

Radiological assessment

Plain X-rays of the hands and feet were taken, and a modified Larsen score from zero to 160 was used to assess radiological joint damage [17].

Statistical analysis

Microsoft Excel 2016 was used to collect and encrypt patients’ data. IBM SPSS Statistics, version 25, was used for statistical analysis. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to test the normality of the continuous data. Means and standard deviations were used to present the quantitative data, while numbers and percentages were used to present the qualitative data. The χ2 test was used for the qualitative data, Student’s t-test was used for normally distributed quantitative variables, and the Mann-Whitney test was used for non-normally distributed quantitative variables. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (Spearman’s rho) was used to assess correlations. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was used to evaluate the specificity and sensitivity. The test was considered significant at p-value < 0.05.

Results

This study included 70 RA patients and 40 healthy controls. The patient group consisted of 18.6% males and 81.4% females with a mean age of 41.57 ±8.74 years, while the control group consisted of 25% males and 75% females with a mean age of 39.78 ±7.26 years. The patient and control groups were matched regarding age and gender (p > 0.05), as shown in Table I.

Table I

Demographic data of patients and controls

| Variable | RA patients (n = 70) | Controls (n = 40) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age [years], mean ±SD | 41.57 ±8.74 | 39.78 ±7.26 | 0.222 |

| Sex [n (%)] | |||

| Male | 13 (18.6) | 10 (25.0) | 0.425 |

| Female | 57 (81.4) | 30 (75.0) | |

Clinical characteristics and therapeutic data of rheumatoid arthritis patients

The studied patients had a mean disease duration of 8.06 ±4.28 years. Regarding the clinical manifestations, arthralgia accounted for 71.4%, arthritis 60%, morning stiffness 42.9%, and extra-articular manifestations 5.71%. The mean Larsen score of our patients was 52.71 ±23.73, and the mean DAS28 was 3.79 ±1.18. Regarding the therapeutic data, 60% of our patients were receiving methotrexate, 40% leflunomide, 34.3% hydroxychloroquine, 5.7% sulfasalazine, 10% golimumab, 8.6% etanercept, and 17.1% baricitinib, as shown in Table II.

Table II

Clinical and therapeutic data of rheumatoid arthritis patients

Laboratory data of participants

Rheumatoid arthritis patients showed significantly high ESR and CRP, and low hemoglobin compared with the controls (p < 0.001, p = 0.002, and p = 0.005), respectively. A significant increase in the serum level of cystatin D was observed in RA patients compared with the controls (p < 0.001). The patients had a mean RF of 116.56 ±157.26 and a mean ACPA of 61.57 ±93.05. Regarding the RF positivity, we found that 60 patients (85.7%) were positive, and ten patients (14.3%) were negative. In addition, we found that 43 (61.4%) patients were positive for ACPA, and 27 (38.6%) were negative, as shown in Table III.

Table III

Comparison of laboratory data between patients and controls

| Variable | RA patients | Controls | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| ESR [mm/h] | 42.73 ±28.17 | 5.60 ±2.34 | < 0.001*** |

| CRP [mg/l] | 15.67 ±17.61 | 6.72 ±4.41 | 0.002** |

| Serum creatinine [mg/dl] | 0.73 ±0.21 | 0.80 ±0.18 | 0.051 |

| AST [U/l] | 20.72 ±7.25 | 22.45 ±5.48 | 0.130 |

| ALT [U/l] | 24.86 ±7.33 | 21.80 ±7.47 | 0.052 |

| Hemoglobin [g/dl] | 11.78 ±1.56 | 12.47 ±0.96 | 0.005** |

| WBCs [× 109/l] | 7.34 ±2.90 | 6.61 ±0.97 | 0.057 |

| Platelets [× 103/µl] | 287.49 ±78.60 | 266.23 ±67.02 | 0.153 |

| Cystatin D [ng/ml] | 4.67 ±1.04 | 3.09 ±0.81 | < 0.001*** |

| RF [IU/ml] | 116.56 ±157.26 | – | – |

| ACPA [U/ml] | 61.57 ±93.05 | – | – |

| RF-positive [n (%)] | 60 (85.7) | – | – |

| ACPA-positive [n (%)] | 43 (61.4) | – | – |

The correlation between cystatin D and other disease parameters

Cystatin D was negatively correlated with ESR (r = –0.490, p < 0.001), DAS28 score (r = –0.512, p < 0.001), total Larsen score (r = –0.349, p = 0.003), Larsen score of patients ≤ 2 years disease duration (r = –0.644, p = 0.024) and Larsen score of patients > 2 years disease duration (r = –0.311, p = 0.017), as shown in Table IV.

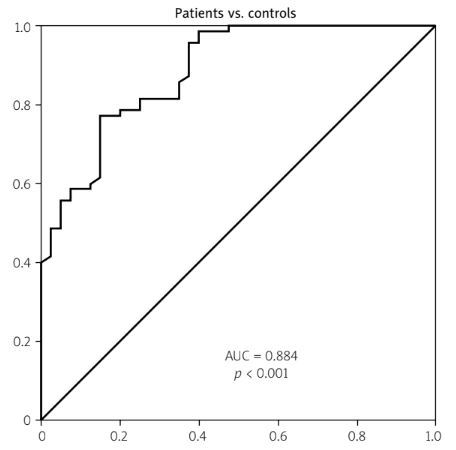

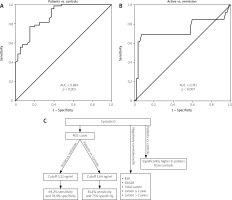

Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis of serum cystatin D level in rheumatoid arthritis

The receiver operating characteristic curve analysis showed that at a cutoff value of 3.64 ng/ml, cystatin D level could differentiate RA patients from healthy controls (p < 0.001) with 81.4% sensitivity and 75% specificity, and the area under the curve (AUC) was 0.884, as shown in Table V and Fig. 1A.

Table V

Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis of serum cystatin D level in rheumatoid arthritis patients

| Cutoff value | AUC | Sensitivity | Specificity | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients vs. controls | 3.64 ng/ml | 0.884 | 81.4% | 75% | < 0.001*** |

| Active vs. remission | 5.22 ng/ml | 0.741 | 69.2% | 78.9% | 0.007** |

Fig. 1

A) ROC curve analysis of cystatin D in RA patients vs. controls. B) ROC curve analysis of cystatin D in active RA vs. remission. C) Graphical abstract for the role of cystatin D in RA.

DAS28 – Disease Activity Score in 28 joints, ESR – erythrocyte sedimentation rate, RA – rheumatoid arthritis, ROC – receiver operating characteristic.

Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis of serum cystatin D level for disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis patients

The receiver operating characteristic curve analysis of cystatin D for disease activity revealed its significance (p = 0.007) at a cutoff value of 5.22 ng/ml to differentiate active RA patients from those in remission, with 69.2% sensitivity and 78.9% specificity, and the AUC was 0.741, as shown in Table V and Fig. 1B.

The role of cystatin D in RA was represented as a graphical abstract (Fig. 1C).

Discussion

Rheumatoid arthritis is an immune-mediated disorder characterized by chronic inflammatory changes, which lead to synovial membrane overgrowth and consequent bone and articular cartilage destruction [18, 19]. Joint damage is the leading cause of disability in RA patients, so controlling joint inflammation and minimizing joint damage are the main goals to prevent the development of disability; this can be achieved through regular assessment of disease activity and adjustment of therapy [20]. A wide range of biomarkers in RA patients’ serum have been used to assess disease activity. Unfortunately, there is a lack of specific markers to shed light on the underlying disease pathophysiology and help predict its clinical course [21]. Hence, searching for new biomarkers with good sensitivity and specificity for disease activity is essential.

Cystatin D represents an inhibitor of cysteine proteases related to bone resorption; it emerges as a potentially valuable and promising biochemical marker. Enhanced proteolytic activity is reported to contribute to the pathophysiology of joint inflammation and articular cartilage destruction [22, 23]. According to our knowledge, few researchers have investigated the role of cystatin D in RA patients, and our study is the first that sheds light on its relation to radiological joint damage.

We found a substantial increase in cystatin D levels in RA patients compared to the control group (p < 0.001); this agrees with Mohammed et al. [24], who found a significantly higher cystatin D serum concentration among RA patients compared with healthy controls. Moreover, cystatin D was negatively correlated with DAS28 (r = –0.512, p < 0.001), Larsen score (r = –0.349, p = 0.003), and ESR (r = –0.490, p < 0.001). In agreement with our findings, Mohammed et al. [24] reported a negative correlation between cystatin D level and DAS28 score and ESR.

The role of cystatin D in delaying joint damage in RA patients can be explained by the inhibitory effect of cystatin D on cathepsins H, L, and S. Cysteine cathepsins are known as cysteine proteases; their role in the pathogenesis of RA is exerted through their proteolytic activity leading to bone and cartilage damage [25]. The pro-inflammatory cytokines stimulate the expression of proteases, particularly cysteine cathepsins and MMPs, which are involved in joint destruction [26]. Cathepsin S and L are detected in the synovial fluid and membrane of patients with RA, suggesting their role in the inflammatory and destructive process in RA patients [27]. Cathepsin S was found in B cells, macrophages, and dendritic cells. In addition to being expressed in synovial macrophages, cathepsin S has a powerful proteoglycan-degrading effect, and inhibitors of cathepsin S have been discussed as future therapeutic options for inflammatory arthritis [28]. Cathepsin L is required for migrating blood-borne mononuclear cells into the synovium and degrading collagen and cartilage components. Its effect is achieved by binding and attaching the hyperplastic synovial lining to the bone, forming a pannus. As a result of pannus invasion, matrix degradation may develop. These findings suggest that cathepsin L may contribute to joint erosions in RA [29]. Brage et al. [30] stated that cystatins D and C reduce bone resorption and the formation of osteoclasts in bone marrow cell culture.

According to ROC curve analysis of cystatin D for RA, at a cutoff value of 3.64 ng/ml, cystatin D could discriminate RA patients from healthy controls (p < 0.001) with a sensitivity of 81.4% and a specificity of 75%. Also, our findings from ROC curve analysis revealed the importance of cystatin D level for the detection of RA disease activity with a sensitivity of 69.2% and a specificity of 78.9% at a cutoff value of 5.22 ng/ml (p = 0.007), which agrees with Mohammed et al. [24], who found that serum cystatin D had a high sensitivity and specificity for distinguishing between active and inactive RA patients.

Cystatins, as natural cathepsin inhibitors, can reduce the production and secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor α and interleukin-6, with a resulting anti-inflammatory effect [31]. In a study by Wu et al. [32] on a mannan-induced psoriasis model, they investigated the therapeutic effects of four cystatins derived from the tick’s saliva and midgut. They found that the isolated cystatins have immunomodulatory activities by inhibiting proteases involved in immune pathways, such as cathepsins L, S, and C. These cystatins significantly reduced psoriasis manifestations, severity index, and histological features. Hence, these cystatins may be promising candidates for treating immune and inflammatory diseases. Gao et al. [33] concluded that tick cystatins inhibit the Toll-like receptor-mediated NF-κB, p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase, and Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription signaling pathways, with suppression of inflammation. Thus, these cystatins are promising targets for developing anti-inflammatory or immunosuppressive drugs.

Our research is ground-breaking in terms of shedding light on the inhibitory effect of cystatin D on radiological joint damage in patients with RA, making it a potentially viable prognostic marker, implying that it may be beneficial in conjunction with the DAS28 score for the follow-up of disease progression and guiding treatment decisions. Future studies exploring the inhibitory effect of cystatin D in RA patients, particularly on joint inflammation and radiological damage, should be encouraged, and its role in other autoimmune diseases should be investigated.

Limitations of the study

Lack of follow-up to determine the prognostic value of cystatin D through longitudinal studies exploring the relation between cystatin D and the Larsen score at different time points.

Conclusions

Cystatin D may be a valuable marker for RA with good sensitivity and specificity. Moreover, its negative correlation with the DAS28 and the Larsen score suggests that it may be a marker adding to the DAS28 for the follow-up of disease activity and prediction of radiological joint damage. However, further studies with large sample sizes and long follow-up periods are required.