Introduction

Carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) is the most common entrapment syndrome, accounting for 90% of all focal entrapment neuropathies [1, 2] and affecting 3–6% of the adult population [3]. The symptoms include characteristic pain, numbness, and paraesthesia in the palmar and dorsal distribution of median nerve innervation. As the syndrome progresses, patients may experience motor dysfunction such as weakness and impaired fine motor skills, along with atrophy of the thenar muscles. Although the majority of reported cases remain idiopathic, some predisposing factors have been identified, including wrist trauma and repetitive flexion of the wrist (e.g., while operating machinery or a computer). Females are 3 times more likely to develop this neuropathy, attributed to their higher representation among high-risk professions (e.g., tailors, secretaries) and the anatomically smaller carpal tunnel, which facilitates the occurrence of increased pressure on the structures within it [4, 5]. Moreover, potential genetic factors have been suggested [6]. When evaluating potential risk factors, it is crucial not to overlook the role of rheumatological conditions of the patient, particularly systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), and Sjögren’s disease (SjD).

Sjögren disease, previously known as Sjögren syndrome, is an autoimmune disease characterised by lymphocytic infiltrates in the exocrine glands. However, as the disease progresses, multiple organs can be affected, sometimes leading to life-threatening complications. One of the frequent yet understudied manifestations of this disease is peripheral neuropathy. According to the literature and our clinical experience, the incidence of CTS in SjD patients significantly exceeds that observed in the general population. A review of 11 studies focusing on CTS in SjD patients revealed considerable discrepancies in the reported prevalence. An analysis of 733 patients showed an average incidence of 12.8% (95% CI: 7.2–21.8%), with high heterogeneity across studies (I2 85%) [7]. This article aims to highlight the diagnostic and therapeutic challenges encountered in clinical practice due to potential differences in the pathophysiology of nerve involvement in SjD patients.

Material and methods

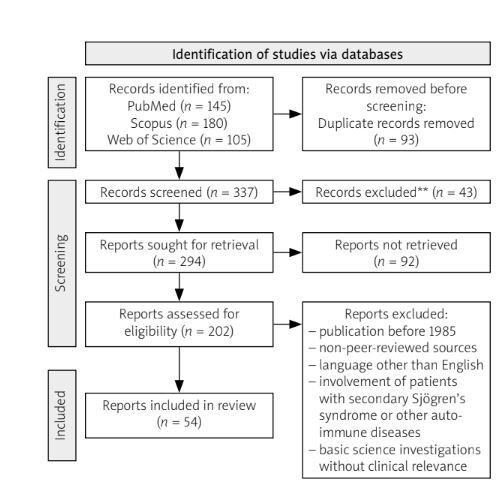

The literature search was conducted using PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science. The search phrase was: (“Carpal Tunnel Syndrome” OR “CTS” OR “Median Nerve Compression” OR “Median Nerve Entrapment”) AND (“Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome” OR “Primary SD” OR “Sjögren’s Syndrome”) AND (“Ultrasonography” OR “Ultrasound” OR “Nerve Ultrasound”) AND (“Neurophysiological Tests” OR “Nerve Conduction Studies” OR “Electromyography”). Only articles published in English between 1985 and 2024 were considered. The search yielded 145 articles from PubMed, 180 from Scopus, and 105 from Web of Science, totalling 430 papers. Inclusion criteria were: focus on CTS in the context of primary SjD (pSjD), relevant data on the prevalence, diagnosis, or management of CTS, published in English between 1985 and 2024 in peer-reviewed sources (including case reports, clinical studies, cohort studies, and systematic reviews). Exclusion criteria included: publication prior to 1985, non-peer-reviewed sources (conference abstracts, opinion pieces), full texts published in languages other than English, involvement of patients with secondary SjD or other autoimmune diseases, and basic science investigations lacking clinical relevance. After initial screening and application of inclusion/exclusion criteria, 202 papers were evaluated by the authors for their relevance to the article question (Fig. 1).

Case descriptions

Case report 1

A 62-year-old female patient was first admitted to Department of Rheumatology, Clinical Immunology, Geriatrics and Internal Medicine of the Medical University of Gdansk in 2014 for diagnostic evaluation. The patient was reporting symptoms lasting approximately 1 year, including joint pain as well as multiple neurologic complaints, such as a subjective decrease of muscular strength in the left upper and lower extremity, and impaired fine hand movements. During the diagnostic workup, positive anti-Borrelia immunoglobulin M antibodies were detected, alongside elevated aminotransferases and creatinine kinase concentrations. Electromyography did not reveal any abnormalities, and magnetic resonance imaging of the brain was insignificant. Despite undergoing doxycycline therapy, the patient continued to experience persistent symptoms. Consequently, a comprehensive evaluation for systemic connective tissue disease was conducted. Based on positive anti-SSA and anti-SSB antibodies, a histopathological examination of minor salivary gland biopsy (focus score > 1) diagnosis of SjD was established. Given the absence of major structural abnormalities that could explain the patient’s symptoms, and the observed improvement in the periods of intensified systemic treatment, the consulting neurologist raised a suspicion of nervous system involvement in the course of pSjD. In November 2014, a nerve conduction study confirmed signs of CTS. The patient underwent surgical treatment (median nerve release), which initially provided relief. However, after a few months, the patient presented again with recurrent CTS symptoms. Treatment with local steroid injections was initiated. A recent ultrasonographic (US) assessment revealed bilateral radiologic signs of CTS, which were later confirmed by neurophysiological studies (demyelinating changes in the electroneurography).

Case report 2

In March 2020, a 52-year-old female patient with a known diagnosis of SjD with central nervous system (CNS) involvement sought treatment at the orthopaedic outpatient clinic due to symptoms characteristic of CTS. Steroid injections had been performed on several occasions, providing only temporary relief. Due to recurrence of symptoms, the patient was eventually referred for surgical treatment and underwent a median nerve release with flexor synovectomy in the right hand in December 2020. The patient continued to be supervised by both orthopaedic and rheumatological outpatient clinics at our hospital. At the time of observation, there were no abnormalities in the laboratory tests, which could explain the complaints (normal thyroid function and electrolyte levels, no vitamin deficiencies). However, in March 2021, the patient reported a recurrence of symptoms. Ultrasonographic assessment revealed no significant abnormalities beyond expected post-surgical changes. Despite this, the patient continued to seek medical attention due to persistent swelling of the operated joint and required repeated steroid injections for symptom relief. The case presents an example of CTS symptoms persisting (as additionally confirmed by neurophysiological studies – axonal-demyelinating changes) despite the application of treatment according to the standard clinical practice. The absence of ultrasonographic abnormalities suggests a different pathophysiology of CTS.

Discussion

Carpal tunnel syndrome – anatomy and pathophysiology

The carpal tunnel is an anatomical region located at the palmar aspect of the wrist. Its base is formed by 8 carpal bones arranged in 2 parallel rows: proximally, the scaphoid, lunate, triquetrum, and pisiform; distally, the trapezium, trapezoid, capitate, and hamate. The roof of the tunnel consists of a thick sheath of connective tissue, the flexor retinaculum, also known as the transverse carpal ligament. This ligament attaches to the tubercle of the scaphoid bone and the ridge of the trapezium on the radial side and to the pisiform bone and the hook of the hamate on the ulnar side. Ten structures pass through this region from the forearm to the hand – 9 long flexor tendons (the flexor pollicis longus, 4 tendons of the flexor digitorum superficialis, and 4 tendons of the flexor digitorum profundus) and the median nerve. While the bony and connective tissue structures provide support and protection, they also create a narrow space with minimal tolerance for volume increase. Nerve entrapment typically occurs at the proximal edge of the carpal tunnel and the hook of the hamate [8]. Repetitive wrist movements significantly elevate the intraarticular pressure by 10-fold on extension and 8-fold on flexion [9], simultaneously leading to oedema around the flexor tendons. In the course of diseases such as RA or SLE, notably in the periods of exacerbation, oedema can be observed in the connective tissue of the joints including wrists [10]. Prolonged compression of the median nerve results in mechanical injury as it traverses the carpal tunnel. Surgical observations from entrapment syndromes’ release procedures describe nerve thinning at the site of compression with proximal swelling [9]. Chronic compression leads to ischaemia and consequently damage of the blood-nerve barrier with accumulation of inflammatory proteins and cells [11]. This condition may eventually mimic the compartment syndrome, where increased permeability facilitates the accumulation of endoneurial fluid, leading to intra-fascicular oedema [2].

Another factor contributing to CTS is anatomical variations, such as high division of the median nerve, proximal to the carpal tunnel, known as the bifid median nerve. Although a rare cause of CTS symptoms, it accounts for approximately 0.8% to 2.3% of cases. This variation increases the cross-sectional area of the nerve, predisposing it to compression in the carpal tunnel [12, 13].

Despite well-documented symptoms of CTS, the clinical presentation alone may be insufficient for a definitive diagnosis. In routine practice, nerve conduction studies (both motor and sensory) are employed to assess the median nerve function. The standard protocol is the one suggested by the American Association of Neuromuscular and Electrodiagnostic Medicine (AANEM) [14–16]. Sensory fibres of the median nerve are examined using the orthodromic method, while compound muscle action potential is recorded from the abductor pollicis brevis muscle. Carpal tunnel syndrome is diagnosed when characteristic symptoms are accompanied by clinical abnormalities and signs of focal demyelination in the carpal tunnel. The potentials measured on the median nerve across the wrist should be compared to another nerve segment that is not topographically related to carpal tunnel (for instance, radial or ulnar). Other diagnostic modalities, such as vibrometry threshold testing, current perception testing, and Semmes-Weinstein monofilament testing, have not been proven as sensitive as traditional nerve conduction studies [9].

Increasing attention is being given to US as a diagnostic tool. With the growing availability of portable devices and improved physician proficiency in US examination, US constitutes a more patient-acceptable alternative to neurophysiological testing. Beyond diagnosis, based on the cross-sectional area of the median nerve, US allows for the evaluation of additional factors, such as potential causes of CTS occurrence (thickness of the transverse ligament), as well as performance of dynamic tests or elastography of the surrounding tissues [17]. Interestingly, studies suggest a correlation between US findings and the neurophysiological assessment of CTS severity [18]. Moreover, US may play a role in treatment, including corticosteroid injections and US-guided carpal tunnel release [19].

Patients typically present with pain, numbness, and paraesthesia in the palmar and dorsal distribution of median nerve innervation. However, the symptom presentation varies considerably, as described in a 1999 study by Stevens et al. [20]. In this study, which included 159 patients with electrodiagnostically confirmed CTS, symptom assessment via a questionnaire revealed that symptoms were more frequently reported in both the median and ulnar digits rather than the median digits only. Additionally, 21% of patients reported forearm paraesthesia and pain, 13.8% elbow pain, 7.5% arm pain, 6.3% shoulder pain, and 0.6% neck pain. These findings underscore the importance of comprehensive electrophysiological assessment in the diagnostic process.

Sjögren’s disease

Sjögren’s disease was first described in the early 1930s by the ophthalmologist Henrik Sjögren, who observed remarkable dryness of the eyes and oral cavity in a patient with articular deformities [21]. Sjögren’s syndrome can be classified as pSjD or secondary to other rheumatic diseases. This autoimmune disorder affects 0.2–2% [22] of the global adult population, with a female predominance (male-to-female ratio of 1 : 9). Disease onset typically occurs between the fourth and sixth decades of life [23]. The hallmark “sicca” symptoms result from lymphocytic infiltration of exocrine glands. Therefore, abnormalities found in patients include dryness of the eye, dryness of the oral cavity (which may lead to impaired consumption of solid foods), and parotid gland enlargement. Clinicians should bear in mind other, extraglandular manifestations of SjD, which patients may report as more significant, mimicking other conditions and delaying the diagnosis. Systems potentially affected include cardiovascular, musculoskeletal, gastrointestinal, respiratory, and urinary. Additionally, skin changes can be observed, particularly with vasculitis pattern [22, 24, 25]. The diagnosis is based on the 2016 European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology/American College of Rheumatology diagnostic criteria [26].

Nervous system involvement in SjD is an understudied yet clinically significant aspect, affecting both the CNS and peripheral nervous system (PNS) in 6–48% and 2–60% of cases, respectively [27–31]. The high discrepancy regarding data on the prevalence of neuropathy results from the retrospective character of studies, particularly since patients are not routinely screened for nervous system involvement until symptoms become severe and significantly diminish the quality of life. Peripheral nervous system involvement can have diverse presentations: sensory neuropathies, axonal sensorimotor polyneuropathy, mononeuropathy, multiple mononeuropathy, demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy, cranial neuropathy, and autonomic neuropathy [32]. Such diversity poses a notable difficulty mentioned by the authors of literature reviews – multiple scholars researching the subject tend to use diverse terminology, which may impair results sharing and comparison [7, 33]. Interestingly, nervous system involvement symptoms may precede typical dryness symptoms and the pSjD diagnosis [34]. This article presents collective data on peripheral neuropathy with a special focus on the information related to CTS.

Carpal tunnel syndrome as a peripheral neuropathy presentation among primary Sjögren’s disease patients

Peripheral neuropathy has been well described in several systemic diseases, including systemic vasculitis (prevalence up to 70% of patients) [35], SLE (15% of patients) [36, 37], and SjD (up to 60% of patients) [38]. As of today, there are still limited data regarding the pathophysiology of this phenomenon. Naturally, various autoimmune factors are suspected. Some researchers indicate the potential influence of antinuclear antibodies, anti-SSA, and anti-SSB antibodies and their affinity to different nervous fibres as well as the role of rheumatoid factor [39, 40]. Others direct attention towards laboratory findings which could facilitate early detection of disease exacerbation and foresee probable development of neurological symptoms. Those factors include lowered concentration of complement components, especially C3 and C4, hypergammaglobulinemia, and vitamin D deficiency with its immunomodulatory action [41–45]. Our observations revealed a positive correlation between the concentration of β2-microglobulin and the occurrence of CTS [46]. When analysing the history of patients with PNS involvement, factors such as a longer course of the disease, the presence of Raynaud’s phenomenon and vasculitis have been noted [7, 47].

As mentioned above, a review of 11 studies focusing on CTS in SjD patients showed an average incidence of 12.8% (95% CI: 7.2–21.8%) with high heterogeneity across the studies (I2 85%) [7]. Despite discrepancies among studies, likely due to a shortage of prospective studies, this result proves that CTS is more common among pSjD patients than in the general population (12.8% vs. 3–6%, respectively). According to some authors, the above-mentioned autoimmune mechanisms are unlikely to cause mononeuropathies, due to their systemic nature (inherently affecting the nervous tissue in a widespread manner) [33]. As previously mentioned, PNS involvement may precede the occurrence of other, more typical symptoms of SjD and the definite diagnosis. It cannot be ruled out that some of the patients initially presented with symptoms of CTS (perhaps non-standard) which resolved in the course of immunosuppressive therapy. The highest efficacy of treatment for peripheral neuropathy in autoimmune diseases is attributed to orally administered steroids and intravenous immunoglobulins. There are also reports of successful rituximab usage for vasculitis-related peripheral neuropathy in pSjD patients [7, 47].

Clinical implications

The distinct pathophysiology of peripheral neuropathy in pSjD, including CTS, may significantly affect the therapeutic process, for both those with a known diagnosis and patients searching for medical help for the first time.

Typically, general practitioners refer patients with CTS symptoms to orthopaedic surgeons as the first-choice specialists, believing that surgical treatment is ultimately more effective than conservative therapy [48]. In-depth history taking at this point could facilitate the choice of therapeutic method [49]. If the patient reports any additional neurological symptoms, paraesthesia in other body regions, signs of ataxia, or sicca symptoms that cannot be attributed to any known chronic disease of the individual, such a person should be referred to a rheumatologist for diagnostics. When gathering the medical history, it is important to specifically name the symptoms which may be of interest. On the one hand, some of those suffering from chronic pain tend to under-report complaints, considering them insignificant and having become habitual to them or due to concerns of, for instance, a financial nature [50]. On the other hand, according to our previous studies, patients tend to over-report symptoms indicative of peripheral neuropathy, which do not comply with abnormalities found in diagnostic tests (80% of patients reporting symptoms vs. 46% of patients with established diagnosis of polyneuropathy) [41]. Practically, this may lead to a lengthy list of complaints from the patient that do not form any clinical pattern and may cloud the physician’s judgment.

As described above, in terms of patients suffering from PNS complaints in the course of autoimmune diseases, the most effective therapeutic method proves to be immunosuppressive treatment. Our clinical observation shows that in the case of pSjD patients, there is no significant correlation between joint involvement in the course of the disease and electrophysiological diagnosis of CTS, unlike in the case of RA or SLE [46]. As a consequence, surgical intervention with the release of tension within the carpal tunnel may not bring desired long-term results. At the same time, any surgical intervention in rheumatological patients, especially those undergoing immunosuppressive treatment, carries an increased risk of infection, post-surgical complications, and exacerbation of the patient’s initial disease activity [51].

Conclusions

The presented analysis of this topic based on literaure review and clinical picture in cases desriptions, highlighting the diversity of the pathogenesis of CTS and its further clinical implications. Physicians frequently encounter complaints related to the hand and wrist as they significantly affect the daily activities of the patients. Particularly in patients with multiple complaints and after unsuccessful therapeutic interventions, a rheumatic diagnosis should be considered. Moreover, the observations made by our team highlight the need for further research into the mechanisms behind the higher prevalence of CTS among SjD patients to enable a more unified, interdisciplinary, patient-focused treatment approach.